A little more than thirty years ago, I went to a school run by the military. It was a suffocating place. The school stood within the distance of a rifle shot from the great Baroque palace at Ludwigsburg, built by the autocratic rulers of the duchy of Württemberg as a scaled down version of the French court of Versailles. The Ludwigsburg Schloß was massive and its formal French gardens seem almost endless.

And two hundred years earlier there was another military school in the shadow of the castle, run and named for Duke Karl Eugen, the Karlsschule. The duke brought many of the most promising children of his little realm there to train them for his service, and the school was run with stark military discipline. He presented himself as a harsh father-figure to the students, demanding absolute and unquestioning obedience from them. And what did it mean to serve this sovereign? Karl Eugen maintained a fine army, and he saw it less as a way of keeping his little duchy free and secure and more as a means of making money. He sold his soldiers into mercenary service under his “cousin,” King George III. They traveled across the ocean to fight the colonists in America. And for Karl Eugen, this was an investment in the future, for he saw no menace in the world quite so severe as the notion of the American yeomen rising against their lord and master.

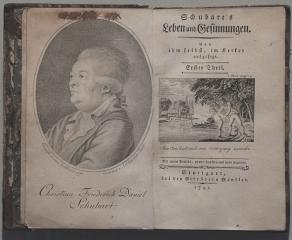

One of the young students was the son of the great eighteenth century poet Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart, who then earned his bread as an organist in a near-by church. Schubart was, however, something of a free spirit, and Lutheran church music was not his thing. Parishoners were soon complaining–he had taken to punctuating the church services with passages from Rameau’s operas in the style gallant, the music of the Enlightenment. Schubart found the entire environment oppressive, and he was deeply troubled by what he saw happening at the school. The duke was taking free spirits and breaking them. He made slaves of free men; he was an oppressor. Schubart left and began to publish a newspaper, one of the region’s first, and he began to pursue exposé journalism. And at the same time, his poetry took an increasingly sharp edge. “When Dionysius of Syracuse ceased to be a tyrant/He took up running a military school,” he wrote.

Karl Eugen flew into a rage. He lured Schubart back for a visit with false promises and assurances, and as soon as he was on the duchy’s soil, had him arrested and thrown in the prison at Hohenasperg. There were no charges, nor a trial, nor a dream of habeas corpus. The autocrat’s whim was sufficient and complete. And for Schubart there was no hope. In September 1783, he wrote his wife:

I have been damned to spend my life in misery, as a sacrificial lamb for all of you. My sole consolation lies in the absolute conviction that I did nothing to earn this fate. As of today I have suffered 2,426 days in this dungeon. What did I do to deserve this?

But among the students in the Karlsschule, many followed the fate of Schubart with concern. He was a figure of nobility and respect for them, and his willingness to speak truth to power—to use his poetic talent to openly label a tyrant as a tyrant—was a heroic act.

One of the students, destined to serve as a regimental doctor, took poetic inspiration from Schubart’s suffering and began to write plays. His writings were marked by a revolutionary pathos; they decried the conduct of tyrants and made heroes of those who stood their ground for human dignity and freedom. For this young doctor, the plight of Schubart, rotting away in a fortress prison, and the uprising of the Americans across the ocean were about the same thing: an insatiable cry for freedom.

“As the Americans are gaining their freedom, I have resolved to go there. Something courses in my veins—I am intent in this uneven world to make some leaps which will furnish material of which people will speak in the future,”

he wrote to a friend, also in 1783. The young doctor never made it to America. But it’s clear that something of the spirit of America made it into him. He launched a literary career which had few parallels in European history. He was the philosopher-poet of freedom, the author of the Ode to Joy that inspired Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and went on to become Europe’s official anthem. He was Friedrich Schiller.

And today, much has changed, yet much remains as before. We still have tyrants who throw their enemies in prison indefinitely without charges and trials. We still have simple-minded and paternalistic autocrats. And now they govern where once was the cradle of liberty. But where today is the cry of freedom?