Michiko Kakutani, “An Epic Showdown as Harry Potter Is Initiated Into Adulthood,” The New York Times, July 19, 2007:

While Ms. Rowling’s astonishingly limber voice still moves effortlessly between Ron’s adolescent sarcasm and Harry’s growing solemnity, from youthful exuberance to more philosophical gravity, “Deathly Hallows” is, for the most part, a somber book that marks Harry’s final initiation into the complexities and sadnesses of adulthood.

Harper’s Index, December 2000:

Rank of the Pope, J. K. Rowling, and God among the “most important people in the world today,” according to U.S. schoolchildren, respectively: 2, 13, 19

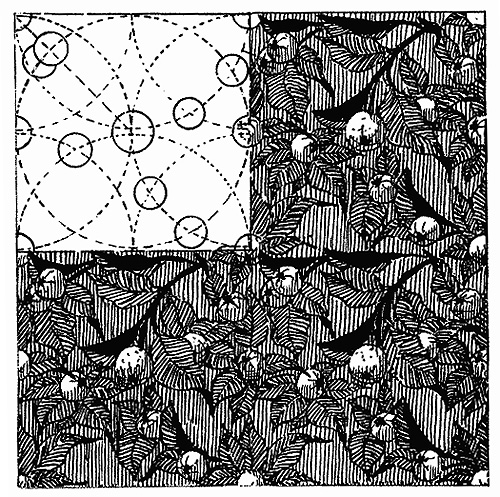

Frances Taliaferro Thomas, “Blackboard Art: The novel goes to school,” October 1981:

Tom Brown’s Schooldays is the archetype of what might be called the novel of assimilation, though I prefer to think of it as the “new kid” story. Everyone will recognize the plot, which can be set just as successfully in a large hospital (Sue Barton, Student Nurse) as in the army (Private Benjamin). A new recruit–young, green, ignorant–is introduced to an old institution. He encounters customs that are strange to him, precious to the inmates. He is bullied by crusty supervisors and loutish peers; he is usually the victim of some injustice; he waits on the fringe of this alien society, and in the fullness of time he redeems himself by some valorous act that initiates him into membership. Respected by his elders, he finds true friendship with the most honorable of his peers. He becomes the vessel of the culture that once seemed so strange . . .

Eight years later, the manly Tom has “fought his way fairly up the School” and is the captain of the cricket eleven. He has achieved his best victories, however, over Satan and his works. The ending of this cautionary novel explicitly reveals the school’s purpose: “[A]ll young and brave souls … must win their way through hero-worship, to the worship of Him who is the King and Lord of heroes.” Tom Brown’s Schooldays became the ancestor of a long line of school novels written for children. At worst, they are little more than manuals of instruction that ease the child’s entry into adult society. At best, these books provide escape into an orderly world whose customs have their own eccentric glamour: merry pranks, saucy nicknames, obligatory “pashes” or “crushes,” midnight feasts. The pleasure is in the feeling of belonging: along with the hero, the reader is accepted into this demanding society. Gratifying these novels may be; works of art they are not.

Harper’s Index, April 2005:

Estimated number of visitors each week to the grave of Harry Potter, a Briton buried in Israel in 1939 : 45

Lewis H. Lapham, “Time Travel,” May 2007:

Why take the trouble to remember what happened yesterday on channels 5 through 9 when tomorrow is available on channels 12 through 24? The national shortage of adult minds suits the purposes of a government that defines its task as a form of child-rearing and guarantees the profits of the consumer markets selling promises of instant relief from the pain of thought, loneliness, doubt, experience, envy, and old age. A country so favored by fortune is one in which no childhood gets left behind. A self-regarding electorate asks of its rulers what the rich ask of their servants: “Comfort us.” “Tell us what to do.” The wish to be cared for replaces the will to act, and in the event of bankruptcy or rain, travelers stranded on the roads from here to there can send an owl with a message to Harry Potter.