Ken Silverstein, “How the Pentagon’s ‘Surrogates Operation’ Feeds Stories Directly to Administration-Friendly Bloggers,” July 19, 2007:

The unit was initially called the “Surrogates Operation” but was later rechristened as “Communications Outreach” after someone realized that the original title, while accurate, was embarrassing for those working with the Pentagon . . . The Surrogates unit arranges regular conference calls during which senior Pentagon officials brief retired military officials, civilian defense and national security analysts, pundits, and bloggers. A few moderates are invited to take part, but the list of participants skews far, far to the right. The Pentagon essentially feeds participants the talking points, bullet points, and stories it wants told.

The U.S. Department of Defense, “Defend America,” 2007:

Welcome to the archives of the “Bloggers’ Roundtable.” Here you will find source material for recent stories in the blogosphere concerning the Department of Defense (DoD) and the Global War on Terrorism by bloggers and online journalists. Where available, this includes transcripts, biographies, related fact sheets and video.

Aldous Huxley, “Notes on Propaganda,” December 1936:

Propaganda by even the greatest masters of style is as much at the mercy of circumstances as propaganda by the worst journalists. Ruskin’s diatribes against machinery and the factory system influenced only those who were in an economic position similar to his own; on those who profited by machinery and the factory system they had no influence whatever. From the beginning of the twelfth century to the time of the Council of Trent, denunciations of ecclesiastical and monastic abuses were poured forth almost without intermission. And yet, in spite of the eloquence of great writers and great churchmen, like St. Bernard and St. Bonaventura, nothing was done. It needed the circumstances of the Reformation to produce the Counter-Reformation. Upon his contemporaries the influence of Voltaire was enormous. Lucian had as much talent as Voltaire and wrote of religion with the same disintegrating irony. And yet, so far as we can judge, his writings were completely without effect. The Syrians of the second century were busily engaged in converting themselves to Christianity and a number of other Oriental religions; Lucian’s irony fell on ears that were deaf to everything but theology and occultism. In France during the first half of the eighteenth century a peculiar combination of historical circumstances had predisposed the educated to a certain religious and political skepticism; people were ready and eager to welcome Voltaire’s attacks on the existing order of things. Political and religious propaganda is effective, it would seem, only upon those who are already partly or entirely convinced of its truth.

The Lincoln Group, “The Good News,” June 2006.

From articles written last October and November by U.S. troops for placement in Iraqi media with the help of the Lincoln Group, a consulting firm working for the United States in Iraq. Editors of Iraqi newspapers were paid up to $2,000 each for printing such stories.

IRAQI ARMY DEFEATS TERRORISM

With the people’s approval of the constitution, Iraq is well on its way to forming a permanent government. Meanwhile, the underhanded forces of Al Qaeda remain bent on halting progress and inciting civil war. The honest citizens of Iraq, however, need not fear these criminals and terrorists. The brave warriors of the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) are hard at work stopping Al Qaeda’s attacks before they occur.

On October 24, soldiers near Taji received a report that terrorists were stockpiling dangerous weapons. The soldiers found over 150 tank and artillery rounds. They destroyed every last round, ensuring they will never be used against the Iraqi people.

Paul Ford, Weekly Review, December 6, 2005:

It was revealed that the U.S. Army was writing positive news stories about the Iraq war, and was then paying to have the articles translated into Arabic and published in Iraqi newspapers. Abdul Zahra Zaki, editor of the newspaper Al Mada, said that if he had known the stories—with titles like “Iraqis Insist on Living Despite Terrorism” and “More Money Goes to Iraq’s Development”—were written by the Army he would have “charged much, much more.”

George William Curtis, “Editor’s Easy Chair,” May 1862:

But we are to remember that very few writers or speakers are in haste to announce that the people wish any thing which they themselves individually do not. And the chance is that they say the people wish it because the speakers think that they ought to.

If we could, therefore, believe speakers and writers to be both sagacious and sincere, their words of this kind would have great weight. But unluckily we are compelled to believe that the phrase “the people wish it” is only a rhetorical phrase. At least there is scarcely a despot in the world who does not despotize in the name of what he calls his faithful subjects. He wears his crown by the grace of God, he says; but he assumes the Ioyalty of his people, and he fights against them, often enough, under the plea of protecting them . . .

It is impossible to determine that the people wish any thing merely because some body says so. We know what we want them to wish-how many of us know what they do wish? It is the very secret of the highest statesmanship in this country to know that, and then to do it. How, for instance, We were mistaken all round in our rebellion. The Southern wise men thought that the North would rise for them. The Northern sagamores thought the South would not rise at all. Each was disappointed. The South did rise, and nobody at the North, but a few feeble, maundering party sots wanted their rebellion to destroy the nation. The people were right, but the doctors all thought them wrong.

Roger D. Hodge, Weekly Review, December 10, 2002:

Prominent American writers such as Richard Ford, Michael Chabon, and Billy Collins contributed to a State Department anthology on what it means to be an American writer. The collection is banned in the United States under the Smith-Mundt Act of 1948, which prohibits the domestic dissemination of American propaganda meant for foreign audiences.

Bernard DeVoto, “Give It To Us Straight!” (Editor’s Easy Chair),”, August 1942:

The official position of course is that we are not conducting any propaganda, foreign or domestic. Actually American propaganda goes out to foreign countries by radio, to mention only one medium, at least eighteen hours a day, and to the home front rather more than that. Many large businesses are advertising themselves by means of war propaganda. The Army, the Navy, the Marine Corps, the Coast Guard, the United States Treasury, the Department of Agriculture, and the services of information themselves are sponsoring radio propaganda. There is nothing evil, offensive, dishonest, or irreligious in that fact. The trouble is that the propaganda is badly done.

In pointing out that the government propaganda is pretty bad, the Easy Chair is not saying that that done by the advertising business or the radio business in general is good. A news broadcast ends: “. . . heroic Americans giving up their lives that you and I may be free. Do your part by buying War Bonds and Stamps. In order to keep fit for freedom, take old Doc Herkimer’s safe but sure Kickapoo Cathartic . . .” When the advertising business forcibly attaches the patriotic sacrifice of soldiers’ lives to somebody’s patent remedy for flatulence it commits blasphemy. But the immediate point is that it also brings war bonds and stamps into disrepute. This is on the level of the local broadcast and the thirty-second “reader.” The mistake is most offensive at that level but it exists also on the level of nationally broadcast programs. Many of these, though laudably designed to unify our feelings and increase our awareness of the war, fail because of their blatant phonyness.

Rightly or wrongly, the radio uses the dramatic sketch as its commonest vehicle. It undertakes to dramatize heroism, battle, patriotic dedication, and the last full measure of devotion. In ninety per cent of its product so far, however, it has achieved only a rich hamminess of content made worse by the resonant falsity of an announcer who heard too many Fourth of July orations when he was a boy and, as an adult, has listened too reverently to the March of Time. The average radio dramatization of heroism presents its heroes shrieking, bellowing, sobbing, moaning, and expressing nobility through a succession of sneezes, belches, and other explosive sounds intended to inform us that the emotions are too grand or too awful for words to convey. Then at the end, an ululating baritone mushy with pumped-up pity or unfelt awe tries to draw the whole thing to a fine point of inspiration by producing bugle tones on the vocal cords. The whole performance is pure corn and its inevitable effect is disgust.

A simple fact accounts for this failure. In some households which the drama reaches, sons or husbands have already been killed in such circumstances as the drama fictitiously portrays, and in thousands of others sons or husbands are expected presently to run their chances of dying in such circumstances. The radio can dramatize these tremendous realities effectively only if it employs a truth which the drama of the stage realized long ago. You can render the tremendous only by understating it, by being simple and concrete, by telling the hundredth part sincerely and letting that one-hundredth suggest the rest–and by underacting it, by being quiet and soft-spoken, by permitting the hundredth part of the emotion to imply the rest. A man or woman whose son has been killed or is risking death for his country is necessarily revolted by the phony noise of an actor who will be lighting a cigarette and calling for a drink as soon as the red light has gone off. The stage learned that principle a long time ago, but the radio has regressed to the ham of a more sentimental day. When asked why, it answers that it has had to. Its effort, it says, is not to convince you and me, sophisticated adults who read Harper’s, but to hold an audience whose mental age is twelve years. It is a bad mistake. The listeners are older than the radio thinks.

Roger D. Hodge, Weekly Review, March 16, 2004:

Congress was investigating videos produced by the White House for local television news programs in which paid actors impersonate reporters and give flattering accounts of the new Medicare law.

Roger D. Hodge, Weekly Review March 25, 2004:

The General Accounting Office concluded in a report that the Bush Administration violated federal law when it produced simulated news spots for local news stations on the new Medicare law; the GAO said that the spots were “covert propaganda.”

Harper’s Index, June 1999:

Ratio of the number of political ads aired last year that used the word “good” to those that used the word “evil” : 44 : 1

D.A. Saunders, “The Failure of Propaganda: And what to do about it,” November 1941:

The Senate Military Affairs Committee nodded approvingly as it listened to Brigadier General John F. Williams, chief of the National Guard Bureau in Washington. General Williams was telling the Senators that “the National Guard is ready and willing to stay in service” as requested by President Roosevelt. A fine group of sturdy young Americans; glad of the opportunity to serve their country, no doubt. But when the olive-drab convoys of the 44th Division roared through Fredericksburg, Maryland, notes were dropped from the speeding trucks which read: “One year’s enough. Send this to your newspaper. Who the hell is General Williams to say the National Guard wouldn’t mind staying another year? No one I know was asked. Why not take a vote among the National Guard?” A corporal in the same division said, “If we are required to stay in longer than a year we’ll be getting a dirty double-cross. Why didn’t they tell us we would be in longer than a year at the beginning? I quit my job in October to volunteer for a year’s service and get it over with so that I might get married. Now they want me to stay longer . . .”

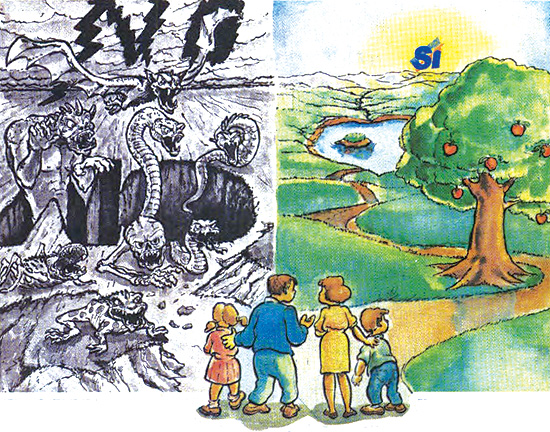

The welfare of America being rightly the first concern of all Americans, we must wake up to the fact that our own propaganda is treading the same weary road, repeating in detail every British mistake. Our own propaganda too has considered the war wholly in “defensive” terms. Every step toward war has been made with the contention that this is the only possible way to keep out. America’s entire relation to the war has been discussed in terms of the most calculating self-interest; the chief arguments seem to have been whether Germany will be a military threat to America if she wins or whether the Nazis will be able to cut in on our South American trade. The very phrases that have been used–“the preservation of our way of life,” “the dignity of the individual,” “the threat to our democracy”–are conservative phrases, referring to things we already have rather than things we mean to achieve. President Roosevelt reiterates that we do not appreciate the full gravity of the situation; we cannot as long as our propaganda is based upon Hitler’s threat to our business interests–interests that are remote indeed from the average man. When Secretary Hull describes Axis maneuvers as “encirclement” of the United States has he forgotten that Hitler has tried this propaganda method and found it wanting? Former Ambassador Bullitt warns us that we may soon become the last stronghold of freedom on earth; can’t somebody find two or three trifling freedoms we do not have now that we could fight for?

These aims are conservative aims, and when advanced (as they frequently are) by conservative men they do not have the millionth chance of serving as a real source of inspiration. The many private agencies striving to “awake America” reveal the same inadequacies. Appeals for the defense of democracy (note that word “defense”) are made in terms of things as they are. Labor is warned that it will lose the privileges it has if the Axis dominates the world; minorities are urged to sacrifice because Hitler threatens their freedom; and all of us are continually pounded with the danger which the Axis represents to our civil rights. The incalculable value of these priceless possessions is granted. But would not all of us be far more inspired at the prospect of achieving something still better?

“China’s Slow News Days,” April 1997:

There have been over 10,000 cases of demonstrations and protests in urban and rural areas within the past year; all of these are not to be covered.