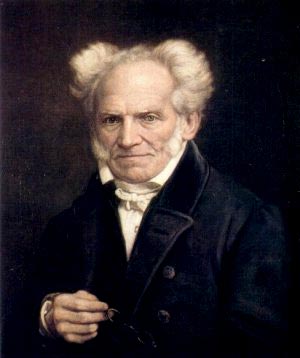

Arthur Schopenhauer, the renowned and eccentric writer whose works on the human will revolutionized modern philosophy was last seen in one of the Taunus mountain resorts up above Frankfurt sometime back. He recently agreed to respond to six questions from No Comment, to help Americans better understand his works and to get his recommendations for a summer reading list. The transcription was complicated a couple of times due to the vexatious barking of his poodle, “Butz.”

1. Professor Doktor Schopenhauer, some of your critics say that your core writings are not much more than a transposition of Buddhist religious texts into the language of the Western philosophical tradition. Can you respond?

Well, what was left? Moses Mendelssohn had already turned Judaism into a philosophical system; Immanuel Kant had extracted a comprehensive system of moral philosophy from Christianity. And then we have that scoundrel Fichte who made a very bad pass at the same thing, together with Schleiermacher, who got off to a decent start but went sour. The obvious next project was Buddhism. It worked beautifully, didn’t it? And what is Western metaphysics compared to the Buddhist tradition? An anemic imitation.

2. In his Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen, Friedrich Nietzsche praised you and described you as his mentor. But then later he described you, together with Christianity, as the “enemies of his life.” What led to this falling out between yourself and Nietzsche?

There are two explanations, really. The simple one is that the Nietzsche who was filled with praise and admiration was the mentally healthy Nietzsche, and the late phase Nietzsche was in the midst of syphilitic delusions. I mean – who in his right mind would name me in the same breath as Christianity? But then of course I can’t avoid coming to some conflicts in our thinking.

Man can never find Happiness because his Will is coextant with life, and it can never be satisfied. This is also seen in all human striving and wishes, which convince us that their fulfillment is the final goal of the Will. But as soon as realized, they appear so to us no longer, and are hence quickly forgotten, antiquated, and actually, if unsatisfying, are cast aside as deceptions. Lucky enough, when something else remains to be wished for and striven after, for then this play can continue from want to satisfaction and then to new want, this painful river of happiness and boredom. To be stuck with merely one satisfaction would leave us with terrible boredom and a flat yearning for no particular object. When knowledge enlightens the Will, it may learn what it wills here and now, but never what it wills in general; every individual act has a purpose, but the Will as a whole has none. Thus Will is a phenomenological fact of life.

Fritz thinks this makes me into a hopeless and eternal pessimist. But for me recognition of these facts is the starting point in a search for peace from reconciliation with the forces of Will. Fritz has rejected Christianity. But he is desperate for a perspective which is more life-affirming than mine. And this leads to his theory of eternal recurrence (ewige Wiederkehr) – remember he writes in the passage “On Redemption” (what a name!) that the Will cannot “will backwards,” because of the limitations of time – so recurrence becomes a way out of this. Some brilliance there, no doubt, but also an awful lot of syphilis floating around in that brain. He was a science fiction writer in the end, that Fritz, it’s no wonder that they made a cartoon character out of his major contribution.

3. During your life you said a lot of very unkind things about the Jews. Some say that you were one of the enablers who made rank anti-semitism respectable, paving the way for the holocaust. Considering what happened, do you regret having made some of those harsh statements?

Of course. My negative comments on Judaism were directed towards a religious-philosophical system which – from my perspective – was excessively materialistic. But I made some very unfortunate statements, which reflect the fact that I am by nature something of a misanthrope. Still, perhaps you have lost sight of the fact that there is one nation of which I am, and always was, far more critical: the Germans. They fill themselves with self-importance, with notions of exceptionalism. They sputter polysyllables that they rarely in fact understand; indeed they need all those syllables just to give themselves time to think, because their brains work so slowly. Their nationalism is the worst of all European nationalisms. My father said, back when the Prussians marched into Danzig, that this German nationalism will be the ruin of all of us. He was right, of course. In the meantime, though, the Germans have been tamed. They’re good Europeans.

4. You also wrote a lot about racial theory, saying in the second volume of Parerga and Paralipomena that high civilization belonged only to the northern white races and that even where it was found in more tropical regions there was a paler upper caste that exercised a monopoly on rule. Do you accept that these attitudes are racist and that they served to justify a lot of misery in the colonial era, that has continued even to this day?

Look, I wrote that back in the middle of the nineteenth century. We didn’t know about DNA and genetic make-up. We didn’t know that the genetic differences between Aboriginals in Australia and Nordic peoples in Scandinavia were infinitesimal. Of course, now we know this. And by the way, I do read the New York Times, especially the Science Section. More to the point, back at the time that I wrote this, I was under the influence of the Sanskritic writers of the Vedic period. You can’t be more racist than those people were. You seem to have forgotten that the people I identified as the world’s natural elite actually had brown skin and inhabit what we now call the developing world.

5. You wrote that up to your time, philosophers had been cowardly in their failure to discuss love and sexual liaisons, that these matters were immeasurably important to human society and human dignity, but that we allowed ourselves to be guided in this sphere by an unworthy system of primitive taboos. But your own love life seems to be a series of tragedies involving unrequited love. Can you comment?

On the personal, I retain the right not to comment except to say that I have been released from the world of the physical demands for gratification. But as to sex and society, I believe that the world has made important strides since I was an active player. Darwin, Freud and others helped society understand the issues I raised in a more profound way than I could express them. Still, it must be accepted that the ultimate object of amorous liaisons is more important than nearly any other object of which a man may conceive; and therefore it merits the profound seriousness with which those sober in mind and spirit pursue it. When I say “object,” of course, I mean deciding what will compose the next generation and will constitute the continuation of our species. Any man who fails to think on this, and who instead thinks only of his immediate material gratifications is enchained forever to the wheel of samsara, and will have a lesser life for that reason.

6. Summer is upon us now, and many of our readers are looking for book recommendations. What can you suggest?

Against the unthinking ink-slinging of our day, it is essential that we erect some breakwaters. A prudent reader should not allow himself to be guided by the mindless yapping of commercial interests, which seek always to hawk what has most recently made its exit from the presses. The reader should be conscious of the fact that in the totality of human history, many great and wonderful things have been written, and few if any of them are likely to find their way onto the Best Seller list. The fundamental idiocy of the modern reading public is this: instead of searching out the proven, the true, and the great, there is an instinctive reach for the cleverly attired but vapid new. So my advice to your readers is this: buy the latest Carl Hiassen if you must, but take some time to read a book that was published sometime before you were born, too. It might just help you see your world in different terms. The World as Will and Idea is a great place to start. And it’s marked-down to $14.95 on amazon.com this week.