On July 5, I posted a little piece on Martin Heidegger’s cabin in the woods, located outside of Freiburg, drawing on a wonderful essay written by Leland de la Durantaye, a Harvard philosophy professor, in Cabinet Magazine. In it, Durantaye notes that Heidegger was very fond of hiking allusions, and he cites several, but he missed the significance of one which is very important—the reference to the handful of deep thinkers who live scattered on mountain tops—which was of course drawn from the poetry of Heidegger’s fellow Swabian, Friedrich Hölderlin.

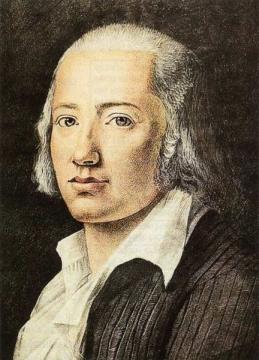

Just as Heidegger can be marked by his “Waldhütte,” Hölderlin can be defined with his tower—a very sad spot down by the river Neckar in the ancient university town of Tübingen where he spent much of his final days in internment. After a brilliant period of productivity, Hölderlin went crazy (how inelegant–the Germans have such a poetic expression for this: er ist in die Umnachtung gegangen, they say, as if he were enshrouded by the darkness of night). He was locked up in this little tower for 36 years while he struggled with sanity. Hölderlin was, of course, Nietzsche’s favorite poet, and Nietzsche followed his path—also falling into the clutches of mental darkness.

In the meantime, I have received a number of notes from readers asking me what, specifically, I was thinking about. The poem in question is called “Patmos.” It dates to 1803, and it is certainly one of Hölderlin’s greatest works—perhaps indeed his greatest. The poem may have the most famous opening of any poem in the German language not by Goethe; it is haunting. (“God is near/Yet hard to seize./Where there is danger,/The rescue grows as well.”) It involves the manipulation of extremely powerful images, it draws very heavily on the classical Greek of the Gospels, and it is filled with the concepts that Heidegger brilliantly develops elsewhere: starting with a fascinating series of juxtapositions of space, time and deeds.

Heidegger has picked up on these concepts and played them out in a way that seems to me to be true to Hölderlin to a certain extent—though there is surely much to distinguish the two.

Start by remembering that Hölderlin, like his fellow students at the Tübingen Stift, read classical Greek fluently and was extremely well read in the classics of antiquity as well as religious texts. I posted earlier this week on another educational institution of the little duchy of Württemberg–the Karlsschule–but the school in Tübingen was still more famous and equally prolific in the training of genius. Consider that one of Hölderlin’s roommates was Hegel.

For Hölderlin the Greek language and its literature presented models of simple, quiet and noble beauty. And he seems effortlessly to bridge the different eras—the Homeric, the classical, the early Christian time, they all seem somehow to fuse together. This poem is a wonderful example of that phenomenon—unity in time. This is not to say that Hölderlin was unaware of the differences between these epochs, but rather that he saw them as a great and powerful historical continuum that links man across time and place—as he calls it, a “golden cord.” But the stronger point is of separation and division—the fact that in each age only a few will see and feel the divine message; others are condemned to repeat the failings and stupidities that are man’s lot.

I set out to find a good English translation of “Patmos” to post, but then despaired. There are several of them out there, some decent, but none of them seems to me to be quite correct—that is they seem mostly to take a sort of Pietist track in understanding Hölderlin, not the philosophical one that Heidegger is following. Having a large number of hours in an airplane, I took my hand to scribbling out a translation of my own, and I have reproduced it below. I welcome the aspiring Hölderlin scholars out there (I could hardly count, though I am a convinced Hölderlin reader and admirer) to point out where I have stumbled. There are no shortage of problematic turns in this piece.

A couple of pointers for those who may approach this without the proper preparation in theology and Greek mythology. Patmos is the island of John the Divine and the book of Revelation, and indeed by legend John saw the revelation which he committed to writing at a particular point, a grotto or sea-cave on the coast. Pat[r]oklos is a river in Asia Minor associated with alluvial gold mining in ancient times, but also the name of the cousin of Achilles who “borrowed” his armor to go to battle Hector with catastrophic consequences. Tmolus is the mountain god who judged the musical contest between Apollo and Pan, also associated with a point near the Lydian coastline, very close to Patmos. Messogis is a chain of hills rising to the east of Ephesus (modern Efes), on the mainland of Asia Minor, close to Patmos.

As I noted, the constant shift from Greek mythology of differing epochs to Christian imagery—the presentation of these perspectives as part of a chain—presents some translation challenges, as in the use of “God” or “god” and “gods.” I made a judgment based on context, but it is not always clear. Of the several images included in this group, the most interesting is, I think, the Last Supper. The German word is Abendmahl, and it would be possible simply to render this as a “dinner,” or “banquet,” and similarly to view the references to wine as Dionysian rather than to the wine transfigured into the blood of Christ at the Eucharist. Hölderlin’s practice here is a careful study in ambiguity.

This poem uses the image of twilight, and it stems from a twilight period in Hölderlin’s life. He had been through a series of traumatic events, including the death of his loved one, and he had just returned from five months in revolutionary France. Friends and acquaintances who saw him around this time were concerned about his health and his sanity. He seemed to be fading into an aethereal world.

In his 1936 essays on Hölderlin, Heidegger writes that “Poetry is the establishment of Being by means of the Word.” He clearly is thinking of this poem and particularly of its last lines, in which Hölderlin writes that God most wants that: “the established Word be/Caringly attended, and that/Which endures be construed well./German song must accord with this.” Heidegger is right about this to an extent, but then he goes off the deep end—calling Hölderlin a radical poet of “national awakening.” That’s absurd. In fact Hölderlin and his friend Sinclair stood under strong suspicion of backing the French. They clearly harbored Jacobin sympathies. They were harshly critical of the oppressive state of affairs in Germany of the small states. Hölderlin had a rather contemptuous view of Germany as a political entity, and of the political supineness of the Germans. “Borniertheit,” he calls it in a letter, which we might render as parochial or petty. Hölderlin embraces a doctrine of radical freedom; he believes this is something to which all men must aspire, and failing that, their lives will be unworthy of humanity. Indeed, in his great novel Hyperion, his hero flees his home because it is under the rule of a despot—he goes to fight for freedom abroad, despairing of when his homeland will gain its freedom.

And Hölderlin’s message at the conclusion is, I think, to be understood quite literally. He was concerned about the development of the German language as an artistic medium. He had an aspiration—namely that it would be possible to think and write great thoughts in this medium, as it was in classical Greek. The key in his mind was a precisely measured use of terminology, and a commitment to the classical model of simplicity of expression and nobility of spirit. This message Heidegger distorted into something crass, political—and ultimately demonic. Hölderlin’s Christian sentiments—his faith in a communion of humankind—disappears into an eruption of Teutonic swamp gas. Viewed with some distance, Hölderlin is a commanding and inspiring thinker, but Heidegger, admittedly taking some inspiration from him, drives straight into an intellectual cul-de-sac.

So “Patmos” is a truly great work of art, a poem grounded in antiquity and pointing into modernity. It deserves to be read—in spite of Heidegger’s perversion of it.