In the past two years, Gov. Tim Pawlenty of Minnesota twice vetoed legislation to raise the state’s gas tax to pay for badly needed bridge repairs–including the interstate bridge that was judged structurally deficient and that collapsed on Friday killing a still-unknown number of motorists. The Bush Administration also repeatedly cut bridge and highway improvement funds for the interstate system from the federal budget. And in light of the absolutely staggering public spending of the federal government under Bush–which has swollen to a size unmatched in the nation’s history–these expenses were a pittance.

On the Sunday talk shows the tragedy in Minneapolis was brushed off as no cause for concern by a number of commentators, all of them Administration apologists, even though the bridge collapse may reflect criminal neglect. America has been shockingly slow to invest in and maintain its own infrastructure, and bridges are a prime example. I live in New York, which probably has the poorest record of bridge maintenance in the country. This past weekend on a drive through the Hudson Valley countryside, my friends made a practice of holding their breath whenever we crossed a bridge.

I was struck by these words published in today’s London Independent:

It may be the wealthiest nation in the world but the U.S. sure has odd priorities when it comes to spending all that cash. Bridges and roads at home are allowed to crumble until the worst happens, while wars and weapons are never too expensive. Budget analysts in Congress last week reckoned the $500bn (£250bn) of taxpayers money allocated so far on wrecking and then rebuilding Iraq will double before it’s all over to $1 trillion. The war now accounts for 10 per cent of everything the government spends.

It is even more depressing when you consider the things that should have public funding lavished on them. It would be nice to see universal health care introduced, but that is too expensive and sounds like socialism. More money for the arts, education and the poor would be good too. And how about choking the torrents (albeit partly from private sources) spent on electing presidents? No one could help but be astounded by last week’s images of the bridge collapse in Minneapolis. The miracle, given the timing in the middle of rush hour, was that more people did not perish. That it happened is not such a surprise, however. We now learn there are tens of thousands of bridges across the US considered “structurally deficient” and in need of repair.

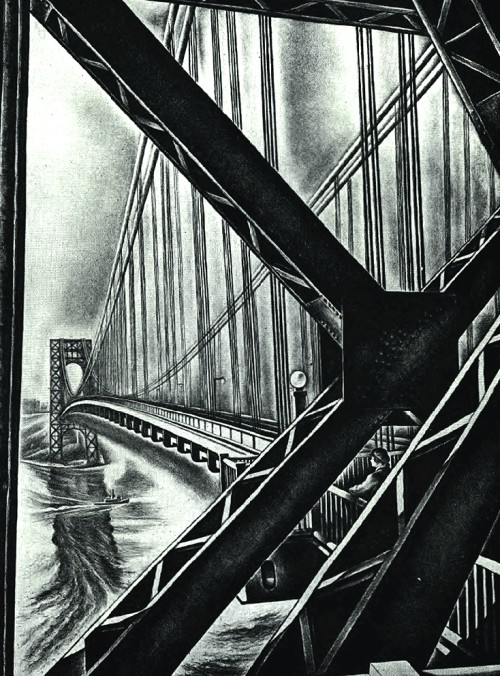

You don’t have to visit this country for long to see how its transport infrastructure has deteriorated since the interstate system was built by Eisenhower in the Fifties. Never taken that pot-holed ride from JFK to Manhattan? Fasten your seatbelts for more turbulence. Or covered your ears in the screeching tunnels of the city’s antiquated subways? As for a cross-country ride on Amtrak, good luck.

It’s also striking how money is spent for wars. Money flies into the pockets of contractors with little accounting, with funds frequently advanced. But when it comes to body armor, plating for vehicles, and, even more importantly, medical care for the wounded vets, the money is missing. It points to a strange set of priorities, and it’s worse than bad judgment: it’s bad morals. War has always been associated with corruption. Toynbee, in his great study of history, makes a point of noting that the most consistent transformative property of war has been the movement of public wealth into private pockets. But America was historically better at guarding against this abuse, and in her better days, America took care of the vital investments that were and continue to be the key to her commercial success. As Thornton Wilder taught us in the Bridge of San Luis Rey, we should be hesitant to see too much in the collection of human stories associated with the collapse of a bridge. On the other hand, the tragedy in Minneapolis gives us pause and the opportunity to ask some fundamental questions about how the public chest is being spent.