It’s the dog days of summer and my colleague Scott Horton is all over the Fredo Gonzales story, and I’d prefer not to write much about the sordid bathroom antics of Larry Craig. (For those following Craig, make sure to read this item from the Minnesota Monitor, which points out that directions to the airport restroom where the senator was busted were available on the gay-cruising website Squirt.org, which rated the restroom as the best in all Minnesota. One poster said the restroom had “a constant flow and variety of hot guys” and another said it was “the best spot for anonymous action I’ve ever seen.”)

So what to do? On the advice of multiple readers, I ran down to the Georgetown University library to pick up a copy of an old article by Iraq war champion Laurie Mylroie. There’s been a lot written about Mylroie–the very best was a Washington Monthly story by Peter Bergen and several authors have alluded to the article in question—“The Baghdad Alternative,” published by Orbis in 1988. But I’d never seen a copy until now. After reading it, I feel confident in describing Mylroie’s piece as the single most embarrassing academic article I’ve ever read, and I would include here a high school essay I wrote on the meaning of Thanksgiving.

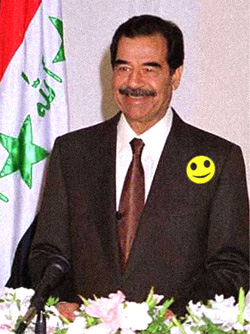

Mylroie, of course, was one of the most enthusiastic advocates for overthrowing Saddam Hussein and over the years sought to tie his regime, unsuccessfully, to everything from the Oklahoma City bombing to the 9/11 attacks. But back in 1988, Mylroie loved Saddam almost as much as Larry Craig loves making friends in public restrooms. She lauded Saddam’s Baath regime for bringing Iraq “stability,” “unprecedented economic growth,” and for its magnificent efforts at “bringing modernity to Iraq.” Women, in particular, had benefited from Saddam’s rule, “with skirts shorter in Baghdad than in Boston.”

Iraq’s good fortune, said Mylroie, was due to the wisdom of Saddam, who was implementing an economic “perestroika” and political “glasnost.” Iraqi officials interviewed by Mylroie told her that Saddam was “much concerned about democracy . . . He thinks that is healthy,” and she wagered this was “not just idle chatter.” From an American perspective, Mylroie concluded, “the more Saddam Hussein exercises control over the Baath Party, including the ideologues, the better.”

The context for the Orbis article was Saddam’s ongoing war with Iran; Mylroie’s belief, which was shared by the U.S. government, was that America should side with Iraq. She proposed that the Bush (Senior) Administration should offer Saddam extensive economic and military aid. “Iraq and the United States,” she wrote, “need each other.”

Sure, Mylroie acknowledged, Saddam had employed poison gas against his own citizens, was guilty of “barbarism” against the Kurds, and his decision to fire off missiles at Iranian cities was rather cold. But it was illogical to “oppose closer relations with Baghdad on the basis of the regime’s atrocities.” After all, Syria and Iran “have no lack of apologists in this country ready to argue for appeasement.” Now Mylroie was making her bid to become apologist-in-chief for Saddam’s crimes.

On a lighter note, Saddam in 1987 had ordered that all government officials “above a certain rank” had to lose weight if they exceeded the standards of the height/weight charts. Some observers saw this decree as evidence that Saddam ruled the country with an iron grip. Mylroie wasn’t so sure, but either way the edict was “not entirely uncalled for” as many Iraqi bureaucrats “tend to an unhealthy girth.” And despite the Iraq-Iran war, things were swell in Baghdad: “There are no tanks or sandbags, no uniformed soldiers. There are no air raids nor public shelters, no bombed and burnt-out buildings . . . Crippled young men do not fill the streets, and there is no rationing. Baghdad to all appearances is a city at peace.”

In far better shape, it would seem, than following the 2003 invasion that Mylroie so confidently predicted would be a cakewalk.