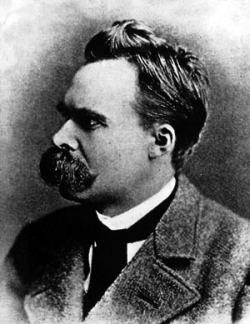

In 1874, Friedrich Nietzsche published his Untimely Observations, the second part of which was called On the Use and Abuse of History. In the core of this work, Nietzsche develops his central thought, namely that the historical obsession of the aspiring bourgeoisie (the Bildungsbürgertum) had laid a number of traps into which society had fallen. We know that as he wrote this he was focused on Friedrich Schiller’s great inaugural lecture, which I discussed here and a number of works by his Basel colleague, Jacob Burckhardt. This is significant because the essay really unfolds as a criticism and assimilation of Schiller and Burckhardt–or more properly, as a very skilled application of their insights to the forces that Nietzsche understood to be afoot in the heart of Europe.

Nietzsche’s introductory observation is that:

While life needs the services of history, it must just as clearly be comprehended that an excess measure of history will do harm to the living.

What on earth did he mean by that? He cites a series of five examples, “illnesses,” he calls them, beginning in chapter 4. Each is an “excess measure” of history. But it becomes clear that he’s talking about distortions or misunderstanding of history, as well as a sense of being bounded by the past in current action. Both of these he sees as social illnesses affecting and limiting the intellect.

The first is the distorted identity of the German nation–and here he is talking about the creation of the Second Reich, which had been proclaimed in Versailles only a few years earlier, and was redefining the nation in very militaristic and authoritarian terms. But he is also concerned with false patriotism; unwarranted disdain for other peoples and cultures; a false pride. The second is the eroded sense of justice–for Nietzsche this was a prime purpose of the state, but he saw it fading in a state where power was the subject of a struggle between traditional military interests and a rising industrial elite. The third was immaturity, namely a failure to strike a correctly critical balance between history and social and human needs. His fourth point turns on the assumption of the image of the epigonos from Greek mythology. This is brilliant but way too complex to get into here. Finally he points to the emerging cynicism of society. Against all of this, Nietzsche advances the perspective that Greek thinkers of antiquity took towards history, namely that it required a balance between consciousness of the past and recognition of the needs of the present. Knowing history does not mean being limited by it. Indeed, knowing history means understanding mistakes of the past among other things. The knowledge must be critical.

Karl Jaspers, I think, hits this Nietzschean-ancient Greek perspective perfectly when he writes:

One must be bound neither to the past not to the future. It is essential to be utterly committed to the present. (Weder dem Vergangenen anheimfallen, noch dem Zukünftigen. Es kommt darauf an, ganz gegenwärtig zu sein.)

Nietzsche’s critique strikes me as very sound especially when we consider it in the circumstances of its writing. He is talking about the new society that was rising in a freshly consolidated Germany. It had great intellectual aspirations—or at least pretenses—but there was a profoundly self-satisfied undercurrent to this historicity. And Nietzsche goes after it very effectively.

I come back to this after re-reading George W. Bush’s speech before the VFW last week, which I discussed in my post, The Weimar President. Again, it strikes me that Bush’s use of history in this speech is consistent, and it is perverse. And Nietzsche’s criticism of the Wilhelmine era historicity of Germany can be transposed and applied with very little change against the Bush historicity.

Bush is using history as a tool with which to enshrine reactionary, militaristic values which do not characterize the wars, conflicts and popular spirit of the times he is describing. In a sense, like the popular historiographers of the Wilhelmine period, he is retrofitting history with a plot line of his own devising. He wants to make the past line up perfectly with his own adventurist policies. And to do this he tried to pound a round peg into a square hole with a sledge hammer. That becomes evident in his revisionist approach to Vietnam. As Jon Stewart reminds us in a too-dreadful-to-be-comic send-up on the Daily Show, only two years ago, Bush was insisting that Vietnam has no parallel to the Iraq conflict. Now he invokes it as an essential parallel. And in the process, we learn that from Bush’s perspective, all the facts about the Vietnam conflict have suddenly changed.

Bush’s speech turned on utterly twisted readings of a number of texts, including Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, which he made stand on its head, and a book by MIT historian John Dowd concerning World War II. Greene is of course no longer with us and able to defend his word from Bush’s acts of intellectual vandalism. But Dowd defended himself with some vigor:

“Whoever pulled that quote out for him [Bush] is very clever,” Dower said, acknowledging that “if you listen to the experts prior to the invasion of Japan, they all said that Japan can’t become democratic.” But there are major differences, Dower said. “I’m not being misquoted, but I’m being misrepresented.”

“In the case of Iraq,” Dower said, “the administration went in there without any of the kind of preparation, thoughtfulness, understanding of the country they were going into that did exist when we went into Japan. Even if the so-called experts said we couldn’t do it, there were years of mid-level planning and discussions before they went in. They were prepared. They laid out a very clear agenda at an early date.”

I want to point my readers to this superlative review of the speech by the blogger Hilzoy at Obsidian Wings–it’s a real tour de force and a demonstration of a recurrent phenomenon: far better analysis of this speech appeared in the blogosphere than in the conventional media.

Bush’s conduct more even than his words show the critical force of Nietzsche’s writing. If Bush is to claim the mantle of a man with an education in history, then it is this one:

The man of historical learning feels that he need do nothing but continue to live in the way he has up to that point, continue to love what he has loved up to that point, to hate what he has hates and to read the same newspapers he has read, for him there is only one sin—to live any differently that he has lived up to that point.

The Bush presidency has been built on a number of sins, but this may be the most fundamental one. All presidents, all leaders, make mistakes. The question is whether they can learn from their mistakes in time to correct them. This is the essence of “the vision thing” which proved so frustrating to Bush 41. But in comparison with his son, Bush 41 is a visionary. George W. Bush cannot understand his mistakes and cannot change his conduct to correct them. He is in this critical sense a prisoner of history, not a man who uses it as a torch on a dangerous path into the future.