For the last ten days we have examined Mark Everett Fuller, the judge who presided over the trial of former Alabama Governor Don Siegelman. The case has now attracted attention across the United States and around the world. Forty-four former attorneys general from across the nation—Democrats and Republicans—have petitioned Congress asking that a special investigation be undertaken to examine the now obvious gross irregularities associated with the case.

One of the most fundamental questions is whether the judge who presided over the trial has a background that should have disqualified him. I believe a careful review of the record leaves no doubt of that. Fuller has a strong record of political engagement, much of it in opposition to Siegelman. After his Siegelman-appointed successor as District Attorney undertook an audit of Fuller’s books, and noted some disturbing irregularities, Fuller claimed this was “politically motivated.” This creates a strong impression that he had an actual grudge against Siegelman. Finally, Fuller appears to generate much of his income from politically-linked contracts awarded by the Bush Administration. It is astonishing that none of these matters were examined or discussed in Alabama as the case was launched. But this reflects the uninformed or at least strangely incurious media that dominates the state.

It is most distressing that Fuller himself failed to do what the canons of judicial ethics required of him, namely, that he recuse himself from the case. He also assembled a small army of marshals in his courtroom, denied routine motions that the defendants be left free pending appeal, and ordered the defendants taken from the courtroom to waiting camera in manacles and handcuffs. This was an offensive bit of political theater, but it could hardly have surprised anyone who observed the trial.

But where did this saga have its start?

William Canary and Karl Rove masterminded the Alabama G.O.P.’s strategy of taking the Alabama courts back in 1994. It was brilliantly successful. It also politicized the process of selecting judges in Alabama, reducing it to a crude spectacle. As the Brennan Center noted in a recent report, Alabama’s judicial races are the most costly in the nation, accounting for more than half of the campaign dollars spent in the ten most active states. The last race for Alabama’s chief judgeship, for instance, was the second most expensive judicial contest in U.S. history—though it was conducted in a state that ranks in the middle of the national roll in population and income. Nearly eighteen thousand advertising spots were run on behalf of the candidates.

But what of those who are not elected, but appointed? From my review of his prior career, I have come to believe that Fuller’s principal qualification for his position was his record of political engagement (campaign manager for Terry Everett, member of the Alabama Republican Executive Committee, etc.). His appointment is a testament to the remarkable success of Karl Rove’s long-term political strategy.

Partisan engagement does not disqualify a person from service as a federal judge. Indeed, judges increasingly get their appointment on the basis of stripes earned in the partisan trenches. But is it appropriate for a judge with a background of this sort to preside over a suspiciously politically charged trial involving a political adversary? It is impossible for a judge to appear impartial in such circumstances, even if the judge sincerely believes he can put his political affiliations to the side.

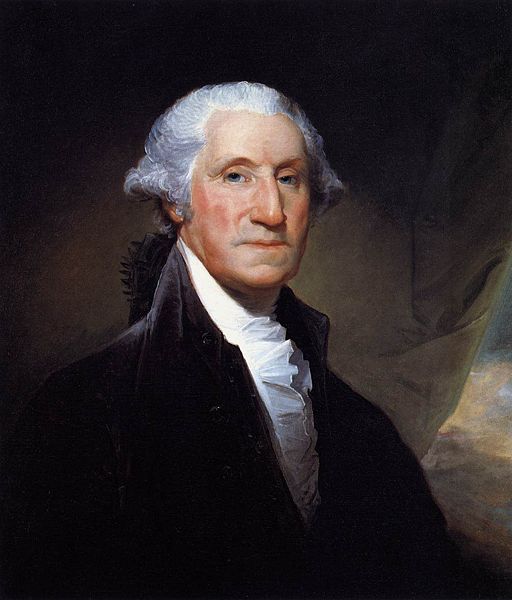

The ultimate test of the integrity of our judiciary rests on the integrity of its judges. The Founding Fathers set a high standard. In 1789, George Washington wrote to his Attorney General Edmund Randolph. The topic was the selection of the first federal judges. “The selection of the fittest characters to expound the law, and dispense justice, has been an invariable object of my anxious concern,” he wrote. He was determined that in proposing candidates there be no blemish of improper favoritism, no suggestion that candidates had been selected on the basis of family or connections with himself or his cabinet, nor indeed that they be viewed as his political adherents. He would have only the best, those who had gained a reputation for standing above the fray, who loved justice more than anything else, who commanded the respect of their contemporaries at the bar.

But today the process of judicial appointments has become a partisan slugfest. Filibusters are threatened and public appeals are launched. At functions organized with the support of the White House and at which senior Republican officials appear—Justice Sunday)—dire threats are directed at judges who fail to perform according to fixed political expectations. The process of judicial appointments has always been a political process, and inescapably so. But never in our history has the partisan aspect of the struggle been so apparent and so damaging to our democracy.

Perhaps Washington’s vision was naïve and unobtainable. But it does embrace something fundamental to the American democracy—that the administration of justice would be divorced from the rough and tumble world of politics–that it would be politically blind.

In passing sentence on Siegelman, Fuller stated: “You and I both took an oath to uphold the law. You have violated that oath.” At present in Alabama, and around the world, there is no shortage of people who see irony in these words. Of course, Judge Fuller has broken no laws. The question is a different one. It is whether Fuller is Karl Rove’s kind of judge: a man who sees a case involving a political adversary in the courtroom as the opportunity for the continuation of politics by other means.

The Siegelman case now passes both for exploration to the Judiciary Committee in the House of Representatives and on appeal to the Eleventh Circuit, and with those steps the hope for justice in this case continues to flicker.