For the last week, we’ve been examining the role played by Judge Mark Everett Fuller in the trial, conviction, and sentencing of former Alabama Governor Don E. Siegelman. Today, we examine a post-trial motion, filed in April 2007, asking Fuller to recuse himself based on his extensive private business interests, which turn very heavily on contracts with the United States Government, including the Department of Justice.

The recusal motion rested upon details about Fuller’s personal business interests. On February 22, 2007, defense attorneys obtained information that Judge Fuller held a controlling 43.75% interest in government contractor Doss Aviation, Inc. After investigating these claims for over a month, the attorneys filed a motion for Fuller’s recusal on April 18, 2007. The motion stated that Fuller’s total stake in Doss Aviation was worth between $1-5 million, and that Fuller’s income from his stock for 2004 was between $100,001 and $1 million dollars.

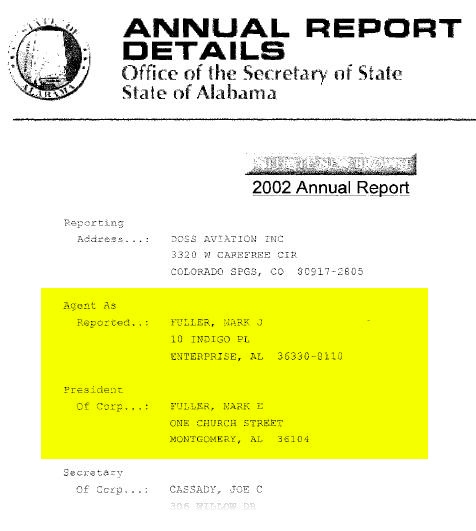

In other words, Judge Fuller likely made more from his business income, derived from U.S. Government contracts, than as a judge. Fuller is shown on one filing as President of the principal business, Doss Aviation, and his address is shown as One Church Street, Montgomery, Alabama, the address of the Frank M. Johnson Federal Courthouse, in which his chambers are located.

Doss Aviation, Inc. (motto: “Total Quality Service Isn’t Expensive, It’s Priceless”) and its subsidiary, Aureus International, hold contracts with a number of government agencies. Quoting from defense counsel’s motion for recusal (emphasis in the original):

Doss Aviation, Inc. has been awarded numerous federal military contracts from the United States government worth over $258,000,000, including but not limited to: An August 2002 contract with the Air Force for $30,474,875 for Helicopter Maintenance, a November 2003 contract with the Navy for $5,190,960 for aircraft refueling, a February 2006 contract with the Air Force for over $178,000,000 for training pilots and navigators, and a March 2006 contract with the Air Force for $4,990,541.28 for training at the United States Air Force Academy. The February 2006 contract with the Air Force for over $178,000,000 is for 10 ½ years, but is renewable from year to year . . .

An Enterprise Ledger article dated April 3, 2005, states that “FBI agents, military and civilian pilots and medical professionals all over the world wear (Aureus International) products which are cut, sewn, inspected, bagged and shipped from its home in Enterprise.”

Doss Aviation and its subsidiaries also held contracts with the FBI. This is problematic when one considers that FBI agents were present at Siegelman’s trial, and that Fuller took the extraordinary step of inviting them to sit at counsel’s table throughout trial. Moreover, while the case was pending, Doss Aviation received a $178 million contract from the federal government.

The Public Integrity Section of the Department of Justice intervened, saying almost nothing about the merits of the motion, but attacking the professional integrity and motives of its adversaries. Here’s an excerpt from the government’s response:

[section title] II. The Petition is the Latest Implementation of Defendant Scrushy’s Bad Faith Strategy to Attack the Integrity of the Judicial Process

As discussed above, the United States submits that the defendant’s Petition is a meritless attack on the District Judge who presided over his conviction by a jury. In light of federal courts’ warnings, cited above, to avoid bad faith manipulations and forum-shopping, the United States notes the following indicators of defendant’s bad faith throughout these proceedings.

Even a quick review and judicial notice of the media accounts surrounding this litigation makes evident that the Petition is just another part of an ongoing and considered strategy of attacking every aspect of the judicial process . . . Immediately after the trial, counsel for defendants Siegelman and Scrushy falsely attacked the conduct of the jury . . .

This, of course, fails to address the legal merits of the motion, merely beating up on opposing counsel.

Judge Fuller denied the motion for recusal. His decision raises three issues:

First, Fuller suggests that he is merely a shareholder in an enterprise. In fact, Fuller’s 43.75% interest in a company with a handful of shareholders makes him the controlling shareholder in a tightly held business.

Second, Fuller derides as a “rather fanciful theory” that he would be influenced by the fact that his business interests derive almost entirely from Government contracts, including from the litigant before the court. It seems that Fuller would have us believe that the process of issuing these contracts is divorced from the political world in Washington. That’s absurd: an examination of press statements surrounding contracts awarded to Doss Aviation shows that Fuller’s political mentor, Representative Terry Everett, is regularly cited in connection with the contract awards. Moreover, the entire process of Department of Defense contract awards is now notoriously politicized through “earmarking” and similar processes that effectively allow legislators to steer lucrative contracts into the hands of their political friends.

Third, Fuller states that he “made several rulings in favor” of the defense. I looked through the record, attempting to find the rulings to which Fuller is alluding, and I can’t find them. It is true that Fuller endorsed rulings that were made by the assigned magistrate-judge on some points, but a review of the record will show that Fuller was relentless in his support for the prosecution and his rejection of defense claims.

At the Edge of Judicial Ethics

The recusal motion points to the difficulties of a federal judge continuing to hold active business interests with entities that litigate before them. Usually, judges divest themselves of such interests and place their holdings in a blind trust. But the evidence offered here raises serious question as to the amount of distance Fuller has put between himself and the business interests that provide the bulk of his income. And in this case there has been at least one clear-cut breach. “Fuller’s designation of his judicial chambers as his address in connection with corporate registrations,” said Nan Aron of the Washington-based judicial oversight organization Alliance for Justice, “clearly runs afoul of the rules, as does his retention of any office, including as agent for service of process.”

Two more cases show a curious attitude towards recusal. First, notwithstanding his former membership in the Executive Committee of the Alabama Republican Party, Fuller participated in the resolution of a highly contentious litigation involving interests of the Executive Committee in a case entitled Gustafson v. Johns decided in May 2006.

Second, there is a case now pending in the Middle District that was initially assigned to Fuller, involving a government contract for the procurement and modification of two Russian helicopters. In the middle of the case sits Maverick Aviation, Inc., of Enterprise, Alabama—the same town from which Fuller hails and where his business operations, which would appear to be similar in scope to those of Maverick Aviation, are sited. From the facts described in several accounts, the company would appear to be a direct competitor with Doss Aviation. Fuller, however, handled this case for several months before his recusal was sought and obtained. The recusal order has been placed under seal, making it impossible to learn what conflicts the parties saw in the matter, nor why Judge Fuller felt free to handle the case for some time before withdrawing. It could be legitimate, or it could be a coverup, and there is no way to find out with the seal in place.

A judge has the responsibility to raise conflict issues on his own initiative—to disclose them to the parties appearing before him, and, when appropriate, to drop out of a case. Judge Fuller, on the other hand, as a committed senior Republican and part-owner of a large business that survives on government contracts, has presided over cases that relate to his personal interests. And that raises questions about the kind of justice he dispensed in the Siegelman case.

Judge Fuller has not responded to a request for comment. I’ll update this post if and when he does.

Next . . . One of America’s Leading Legal Ethicists Discusses Fuller’s Conduct in the Siegelman Case.

Evan Magruder contributed to this post.