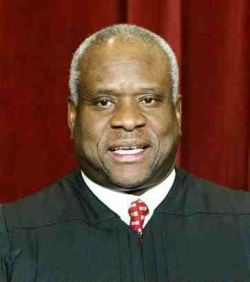

Clarence Thomas, My Grandfather’s Son: A Memoir (Oct. 1, 2007) $26.95

Yesterday, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas appeared on the Rush Limbaugh Show for 90 minutes. Thomas was pushing his new book, My Grandfather’s Son, an autobiographical work. Thomas’s choice of venue was extremely revealing. Limbaugh is a demigod to the rightwing fringe, a master of the outlandish retort, a man known not for being balanced and rational, but rather for being outrageous and over-the-top. And yesterday Rush was back in the public spotlight as controversy swirled around his charges suggesting that any soldiers, serving or retired, who questioned President Bush’s handling of the war were “phony soldiers.” Limbaugh himself, of course—like his judicial guest–never served in the military. He secured a 4-F deferment. But the host and his guest are close, fast friends. Thomas officiated at Limbaugh’s latest marriage, his third, which has already ended in a divorce.

Unlike Limbaugh, Thomas is characterized by public silence. He uttered more words in his appearance on Limbaugh’s show yesterday than he has intoned from the bench in the last fifteen years.

But behind that quiet façade apparently lies a smoldering, angry, revenge-seeking man. NPR’s Nina Totenberg describes My Grandfather’s Son as “a very personal work, indeed so personal that it is at times uncomfortable to read.” She’s being polite–this book is a wild vendetta against Thomas’s perceived enemies. And it’s impossible to read it and not come away with the sense that this is an angry, bitter man. A man convinced of his own rectitude and who believes he was wronged. The class of wrongdoers is pretty expansive—it seems to be everyone who questioned his candidacy for the High Court. And that was a majority of the American public.

To get a sense of it, charge ahead to chapter nine, “Invitation to a Lynching.” It’s the story of Thomas’s nomination contest, probably the most electrifying in American history. I was struck by some of the images that Thomas uses, starting with the lynching, which is drawn from his searing rejoinder during the hearings, which he labeled

a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves, to do for themselves, to have different ideas, and it is a message that unless you kowtow to an old order, this is what will happen to you. You will be lynched, destroyed, caricatured by a committee of the U.S. Senate rather than hung from a tree.

But Thomas also takes a literary approach. He sees himself as a character in the work which I believe may be the most important American novel of the twentieth century, Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. And he cites it to support his characterization of his confirmation hearings as a “lynching.” Here’s the key passage:

Somewhere in the back of my mind, I must have been thinking of To Kill a Mockingbird, in which Atticus Finch, a small-town southern lawyer, defends Tom Robinson, a black man on trial for the rape of a white woman. He was lucky to have had a trial at all — Atticus had already helped him escape a lynch mob’s rope. The evidence presented at the trial shows that Tom’s accuser had lured him into her house, then kissed him, after which he fled. The case against him is laughably flimsy, but in the Deep South you didn’t need a strong case to send a black man to the gallows, and it is already clear that Tom will be convicted when Atticus goes before the jury to make his closing argument.

Thomas quotes the wonderful speech that Atticus gives to the jury. He coaxes them to overcome their prejudices and do justice. In particular he wants them to set aside their prejudices about the moral character of Blacks, in his words,

the evil assumption — that all Negroes lie, that all Negroes are basically immoral beings, that all Negro men are not to be trusted around our women, an assumption one associates with minds of their caliber.

After setting this out, Thomas applies the story to his own life:

I knew exactly what Atticus Finch was talking about. I, too, took it for granted that nothing I could say, however eloquent or sincere, was capable of overcoming the evil assumptions in which my accusers had put their trust. I had lived my whole life knowing that Tom’s fate might be mine. As a child I had been warned by Daddy [grandfather Myers Anderson] that I could be picked up off the streets of Savannah and hauled off to jail or the chain gang for no other reason than that I was black.

So, in Thomas’s retelling of the confirmation struggle, he is the innocent, falsely-accused black man, and his accusers are racist whites who disbelieve him because they are blinded to the truth by their own prejudice. They went out of their way to humiliate and disgrace him with their questioning, he says.

There are some problems with this vision. In fact, just about every element of it is false. Clarence Thomas’s accuser was, of course, not a white woman, but African-American: Anita Hill, now a distinguished professor at Brandeis University. Hill was hired by and worked for Thomas, and she alleged that she was subjected to serial sexual harassment by Thomas at the workplace. Thomas vehemently denied her account, and he and his supporters lashed out at Hill—calling her “nutty and a bit slutty,” suggesting she had been fired by earlier employers and that she was not, as made out, a religious person. Prof. Hill offers an eloquent reply to Clarence Thomas in the pages of today’s New York Times. She writes:

In the portion of his book that addresses my role in the Senate hearings into his nomination, Justice Thomas offers a litany of unsubstantiated representations and outright smears that Republican senators made about me when I testified before the Judiciary Committee — that I was a “combative left-winger” who was “touchy” and prone to overreacting to “slights.” A number of independent authors have shown those attacks to be baseless. What’s more, their reports draw on the experiences of others who were familiar with Mr. Thomas’s behavior, and who came forward after the hearings. It’s no longer my word against his.

Justice Thomas’s characterization of me is also hobbled by blatant inconsistencies. He claims, for instance, that I was a mediocre employee who had a job in the federal government only because he had “given it” to me. He ignores the reality: I was fully qualified to work in the government, having graduated from Yale Law School (his alma mater, which he calls one of the finest in the country), and passed the District of Columbia Bar exam, one of the toughest in the nation.

In 1981, when Mr. Thomas approached me about working for him, I was an associate in good standing at a Washington law firm. In 1991, the partner in charge of associate development informed Mr. Thomas’s mentor, Senator John Danforth of Missouri, that any assertions to the contrary were untrue. Yet, Mr. Thomas insists that I was “asked to leave” the firm.

It’s worth noting, too, that Mr. Thomas hired me not once, but twice while he was in the Reagan administration — first at the Department of Education and then at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. After two years of working directly for him, I left Washington and returned home to Oklahoma to begin my teaching career.In a particularly nasty blow, Justice Thomas attacked my religious conviction, telling “60 Minutes” this weekend, “She was not the demure, religious, conservative person that they portrayed.” Perhaps he conveniently forgot that he wrote a letter of recommendation for me to work at the law school at Oral Roberts University, in Tulsa. I remained at that evangelical Christian university for three years, until the law school was sold to Liberty University, in Lynchburg, Va., another Christian college. Along with other faculty members, I was asked to consider a position there, but I decided to remain near my family in Oklahoma.

One really has to wonder: why is Clarence Thomas drudging all of this out now? Anita Hill’s claims and Thomas’s answers have been exhaustively studied and researched. And the consensus that has emerged is pretty clear: Clarence Thomas perjured himself in the confirmation hearings. Anita Hill was telling the truth. Two major books establish this. One is the award-winning work of Jill Abramson and Jane Mayer, then two Wall Street Journal reporters, Strange Justice: The Selling of Clarence Thomas. That book turned meticulously through the available evidence, and found that it was very consistent—establishing Hill’s veracity and undermining Thomas’s. But far more damning still is the major book which was published to defend Thomas. It was David Brock’s The Real Anita Hill, a work that layed out all the attacks that Thomas and his supporters (most prominently Ted Olson) put forth to protect his nomination. Brock later admitted that his book had been commissioned as a hit job to make Thomas’s position seem more plausible. As he later admitted to the New York Times, “I lied in print to protect the reputation of Justice Clarence Thomas.”

Beyond this, Thomas’s charges about the vicious treatment to which he was subjected don’t stand up. He wants us to think that a group of liberal Democrats destroyed his reputation by rehashing the lurid details of the Anita Hill allegations, eliciting his perjured responses. But go back and examine the transcript. The man who did that was Orrin Hatch, Thomas’s most aggressive supporter on the Judiciary Committee, and the questions were clearly orchestrated and rehearsed to make Thomas fit the role of a martyr or victim.

Aside from these minor details, I approve of the use of To Kill a Mockingbird as a mirror with which to understand Clarence Thomas and his odyssey. Harper Lee’s novel is more than just a retelling of the trial of the Scottsboro Boys with a happy ending. It is more than a story of bigotry in the Deep South. It is a story about the quest for justice, and Atticus Finch is the key character in that struggle.

Atticus is not coincidentally named. His name is derived from an important figure in classical antiquity: Titus Pomponius Atticus, the dearest friend of Cicero, the man to whom De amicitia is dedicated. For Atticus, partisan politics was an abomination: it was the corruptor of society, the subverter of justice. Rather than become involved in the fratricidal squabbles that marked the last days of the Roman Republic, Atticus withdrew from public life. He believed in a reserved judgment, always carefully detached from any bonds of personal friendship, family or partisan alignment. His character has been taken through history, thanks to the glowing portrait of Cicero, as the essence of what is judicious.

And Atticus’s message to the jury was a timeless one. It’s uttered by the small town lawyer Atticus Finch, but it might just as well have been said by the Atticus of antiquity. “Step outside of yourself, and your prejudices. Forget your family, your friends, your politics. When you come to judge, you must lay all of this to one side.”

And that, also, is the essence of the message of the great philosophical work on the art of judgment—Immanuel Kant’s Kritik der Urteilskraft. Kant tells us that detachment is essential to the exercise of fair judgment. We must have a sense of the ethical, he says, and that will inevitably include the sensus communis, a reflection of the values of our society. But the particular personal attachments of family, friends and party are poison to the judicious spirit.

So Atticus Finch is imparting an ancient and very great wisdom; he is giving essential guidance on how to judge.

Now you might think that a person who has taken as his vocation the art of judgment would understand this, and would be moved by it. You would think that such a person would value a reputation for being disinterested and above the petty, highly partisan attachments that are fundamentally disqualifying for a judge. All the sorts of things that Rush Limbaugh and his gutter politics represent, for instance. But then you apparently wouldn’t understand Clarence Thomas.

One message emerges very quickly from a reading of My Grandfather’s Son. It’s that Clarence Thomas has no respect for the values of Atticus Finch. He’s a partisan into the innermost crevice of his soul. And far from being dispassionate and detached, he is filled with burning rage against the Democrats who—in his mind—did him wrong, and determined to use any opportunity that comes his way to strike against them without mercy. As a memoir, this work is very strikingly at odds with the established facts. Readers who want to get the real low-down on what happened in that confirmation battle back in 1991 would be well advised to buy not My Grandfather’s Son, but the Mayer and Abramson book Strange Justice. But Thomas’s book does give us a very clear view of the inner mechanics of his own brain. And what it reveals is the very antithesis of the word “judicious.”

And that leaves us with a question: how can such a person as the author of this book serve as a judge of any kind, much less a judge on the Supreme Court?