Thomas Mann, Meerfahrt mit ‘Don Quijote’ in Gesammelte Werke: Frankfurter Ausgabe, Leiden und Größe der Meister, p. 1018 (1934)

Yesterday, I posted some thoughts about Cervantes’s Don Quixote and what it says to me today, and I paused at the end and wondered: should I say how I came back to Don Quixote? But it seemed to me best saved for a coda. I came back to it thinking of Thomas Mann. In 1934, Mann, who had just been forced to flee Germany by the rise of the Nazis, was asked to cross the Atlantic to promote his book Joseph and His Brothers on the American market. He felt a dark cloud gathering over Europe, he was filled with concerns for the friends and colleagues he left behind, so he undertook the trip with a heavy heart. And he took a single book along with him: Don Quixote in the translation of Ludwig Tieck.

He wrote about this in an essay, “Crossing with Don Quixote,” which was published in a Zürich newspaper when he returned and the reading and his dialogue with Cervantes also appears in the journal entries that Mann kept from the voyage. “Reading material for a trip,” he says, “a category which sounds of something dreadful and inferior.” Mann is right, of course, the bookstalls of our airports and stations are filled with stacks of trashy novels and other low caloric fare. But there’s nothing that requires us to buy rubbish for the road; there’s no reason why we can’t accept the challenge of an intellectual trip that matches the physical one. I was facing a trip to the shores of the Caspian, with a full day in airplanes—not enough to read every page of Don Quixote, but easily enough to make my way into the heart of it.

And Mann’s essay fascinated me. He is filled with dread about the rise of fascism, and those fears are steadily in the back of his mind as he works his way through Cervantes’s novel. And of course, the fascist menace which had risen in Italy and Germany was very shortly to strike Cervantes’s homeland as well. Mann recognizes Don Quixote as the work of a great humanist. But he is troubled by Cervantes’s conformity, by his all too obvious attachment to his patrons, to the court, to the Roman Catholic Church. Germany’s new chancellor is preparing his program and is rushing to its implementation. It includes retaliation against those he considers the nation’s internal enemies, a program under which “non-Aryans” will be labeled, segregated and stripped of the rights enjoyed by most citizens. Many were being thrown in jails and transported to concentration camps. When Mann fled, it was not simply because, being married to a Jew, he feared for her and their children; he feared for himself as well. He had aggressively attacked the Nazis. His books were being burned. But in the age of Phillip II and Phillip III, Spain had entered into a similar program driven by invidious concepts of race. How could a great soul like that of Cervantes write about his homeland and not muster the courage to be critical? Mann is profoundly disturbed by Cervantes’s language, which accomodates and mouths respect for the secular and spiritual authorities who pursued this program of inhumanity:

The genius, the great ego, the lonely adventurer, was an exception produced out of the modest, solid, objectively skilled cult of the craft; he achieved royal rank, yet even so, he remained a dutiful son of the church and received from her his orders and his material. Today, as I said, we begin with the genius, the ego, the solitary—which is perhaps morbid.

But I question Mann’s reading. If you apply the esoteric/exoteric analytical style which was born among the Andalusian masters, starting with Maimonides, then it becomes plain that the comments of the “faithful son of the Church” are to be read as irony, not piety. I cited some examples, but there are more even in the text that Mann works through.

In Mann’s essay he comes to a focus on one particular chapter. It is the famous tale of the Moor’s return (ii, vi, 54). Immediately after the tragicomic story of Sancho Panza’s failed efforts at governance of an island comes the poignant story of a man wrongfully exiled from his home, who risks his life to return. Ricote el morisco, he is called, Ricote the Moor, was Sancho’s neighbor in his native village where he kept a small shop. He was a converso, but because he was an identifiable Moor, he was subject to the edict of expulsion notwithstanding his embrace of the Catholic Church. After travels abroad in France and Germany (which he praises as a land of freedom, to Mann’s amazement), he elects to return to Spain even as he recognizes that if discovered, he may be put to death. Even in presenting this baleful story, Ricote acknowledges that the decision of King Felipe is just.

Not that they were all to blame, for some were true Christians, but these latter were so few in number that they were unable to hold out against those that were not. In short, and with good reason, the penalty of banishment was inflicted upon us, a mild and lenient one as some saw it, but for us it was the most terrible one to which we could have been subjected. Wherever we may be, it is for Spain that we weep; for, when all is said, we were born here and it is our native land.

Mann is moved by the warmth and passion of Ricote’s account, but also at the spinelessness of his acceptance of the policy of ethnic cleansing. Can’t he raise his voice in criticism? Has the Catholic Church expunged the last flickers of love of freedom from him? Moreover, Mann turns to Nietzsche, and cites his still harsher assessment and Nietzsche’s stinging criticism of Christianity in Ecce Homo and Also Sprach Zarathustra.

But are these criticisms—Mann’s and Nietzsche’s—just? Cervantes gives us the story of a converso who is marked by great love of his country, who travels abroad, to Algiers, and finds there “the greatest cruelty and inhumanity.” As he says, he only then learned the value of what he left behind. But let us consider that this Ricote the Moor is remarkably like the author, Cervantes, also descended from a converso of the land about Toledo, also forced to languish for four painful years in Algiers. He has returned to his native land disguised as a pilgrim. He cannot show his true face nor speak with a fully honest voice.

Mann and Nietzsche have, I think, failed to recognize the master’s face in this tale; and they have also failed to detect the tone of irony that flows from his pen. They accept him for a pious and faithful Catholic incapable of uttering the slightest criticism of anything the Church proposes or the king commands. But this is not what I see in Cervantes. He is that returned Moor, cloaked carefully in the guise of the pilgrim (but indeed, it is no disguise, for he is a pilgrim). His heart is heavy and filled with pain, but he avoids bitterness. He turns instead to love for a lost culture of the golden age.

Mann turns to a discussion of Nietzsche—he contrasts the philosopher and his scornful attacks on Christianity with Cervantes, the man he would make into a faithful and unquestioning son of the Church. What a path our European culture has beaten, he seems to say, from the naïve romantic, arch-Catholic Cervantes, to the God-denier Nietzsche, to the storms that encircle Europe today. It seemed predictable, clear, but also resting on some false analysis. But then Mann’s essay come to an astonishing close. It was Mann’s last night at sea, he says, and he experienced an eerie dream.

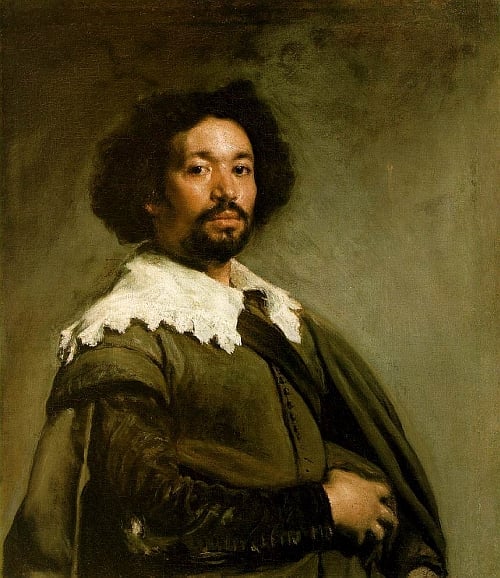

I feel dreamy from the early rising and strange posture of this hour. And I dreamed in the night, too, in the unfamiliar silence of the engines; now I try to recall the dream which found its inspiration in my reading. I dreamed of Don Quixote, it was he himself, and I talked with him. How distinct is reality, when one encounters it, from one’s fancy! He looked different from the pictures; he had a thick bushy moustache, a high retreating forehead, and under the likewise bushy brows almost blind eyes. He called himself not “the Knight of the Lions” but “Zarathustra.” He was, now that I had him face to face, very tactful and courteous, and so I felt very moved by the words I had just read about him yesterday. “Because even when Don Quixote was simply called Alonso Quixano the Good, and also when he was called Don Quixote de la Mancha, he was always a man of the most soft disposition and the most pleasant manner, for which reason he was loved not just in his own household, but by all who came to know him.” Pain, love, forgiveness and boundless admiration overcame me completely as I saw this description realized.

And then Mann tells us he has arrived in New York–the city of the giants! There can be no mistaking this man with a thick bushy moustache and a high retreating forehead who appeared to Mann in a dream as Don Quixote. Certainly he is describing Friedrich Nietzsche, and suggesting that his subconscious has contradicted his conscious in the analysis of Nietzsche and Cervantes. Nietzsche is a later Don Quixote. But in this very strange turn, Mann, I think, comes very close to the truth. And to an appreciation of the radical modernity that lurks deep inside Cervantes’s writing.