Recently, Justice Clarence Thomas gained press coverage and air time in connection with his new book. Its early chapters recount the bitter racism that Thomas faced as a Black man growing up in rural south Georgia. Thomas had a rocky Senate confirmation, but he was confirmed, and he now sits on the High Court. The core chapters of his book relate to the confirmation hearings, which he called a “high-tech lynching” with partisan overtones. That claim is quite a stretch. But another Black man from south Georgia, a contemporary of Clarence Thomas’s, and like Thomas the son of a Georgia sharecropper who knew brutality and racism throughout his life, has been through quite an ordeal. Characteristically, the national press now obsesses with copy on an advertisement by MoveOn, Pete Stark’s outburst, insisting that Bush has recovered his authority by vetoing SCHIP and similar inane blather, pays him no attention. He is now pinning his hopes on an against-the-odds appeal to the Supreme Court. Is his ordeal a “high tech lynching” with partisan overtones? Consider the facts and decide for yourself. In any event, the prosecution is raising eyebrows around the world and is set for a good deal more scrutiny. And this man’s claim to be a victim of vicious and racially tinged persecution is vastly more compelling and credible than Clarence Thomas’s. He’s not racking up press engagements and spending his book advance on fancy vacations. He is in a federal prison in South Carolina and fighting to win back his freedom. And he just picked up a high-profile advocate.

On Tuesday, the House Judiciary Committee will take a look at a series of cases in which the Department of Justice has been accused of bringing politically motivated and timed prosecutions. These cases generally focus on Democratic elected officials who have been charged with corruption offenses. The charges were generally carefully timed to coincide with election cycles. And the charges were generally peddled aggressively to the press. Two men are in the crosshairs in this hearing: Noel Hillman, the former head of the Justice Department’s curiously named Public Integrity Section, and Karl Rove, the man whose phone calls he regularly handled. In the past several months we have explored the prosecutions brought against Governor Don Siegelman in Alabama, Justice Oliver Diaz and Attorney Paul Minor in Mississippi, and Wisconsin public servant Georgia Thompson. In each of these cases, partisan electoral politics was hardly in the background of the prosecution. Arguably, that’s all the prosecution was about.

Another case which will feature on Tuesday turns around Georgia State Senator Charles Walker. His case has not, up until this point, received much attention on the national stage. But that may be about to change.

Charles Walker

Former Senator Charles Walker is one of Georgia’s best known Democratic politicians. He is also an entrepreneur with a focus in the newspaper business. He launched a new paper in his home town of Augusta, the Augusta Focus which broke a long-standing lock on the print media market held by another paper, the Augusta Chronicle. The Chronicle is one of the nation’s oldest newspapers. It is also notoriously close to the Georgia Republican Party and the interests it serves. And, as might be expected, it had close relations with leading players in the community, including the federal judge who came to play the decisive role in the case. Walker served in the state legislature for more than twenty years. He made history in 1996 by being elected as the Senate Majority Leader in Georgia. In fact, he was the first Black to become a Senate leader in the country.

Throughout this period, Walker was one of Georgia’s most prominent Black political leaders. The fact that Walker was targeted because he was a prominent, high profile Democrat is readily established by the Department of Justice’s own internal review of the case. Consequently, of all the political prosecution cases, the Walker case is the one in which the accusations against the Department are made out by its own internal investigations.

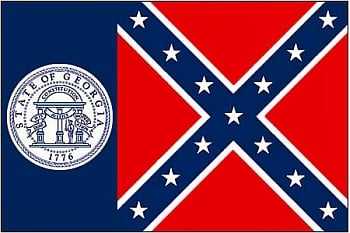

The Flag

A flag is flapping in the background of this case—a powerful and emotive symbol. For some it stands for a romantic past filled with prosperity, wealth, honor and a lost agrarian way of life filed with plantation houses and mint juleps. For others it is a symbol of racism, hatred, oppression, lynch-mob justice and brutality. This flag was waving over the trial that convicted Charles Walker. The question hanging over these proceedings today is whether Charles Walker got the justice that is promised by the American flag, or the retribution and vengeance that is portended by the rebel flag. In some respects his trial amounts to a civil war skirmish fought long after the surrender at Appomattox. And, curiously, the U.S. Department of Justice was plainly aligned throughout with the forces of the Confederacy.

Walker made some bitter enemies. In particular, they were the sort of people who loved to sport and display the battle flag of the old Confederacy, which for Georgia Blacks (and indeed, for most Americans) is closely connected with the Ku Klux Klan and other hate groups. In 1956, Georgia changed its historical state flag so that it prominently featured the old Confederate battle flag. There was never any ambiguity as to why the state did this. It was an act of open defiance in the face of Brown v. Board of Education and the rising federal efforts to eliminate institutionalized segregation. Walker launched an initiative to change Georgia’s state flag, which featured the Confederate flag. And he succeeded. His efforts produced a huge backlash in Georgia, and are often credited with a series of major gains for the Republicans in the 2002 elections.

The Grudge

The man that Walker edged out as Senate majority leader was Sunny Perdue. After his defeat Perdue left the Democratic Party and quickly came to lead the Republicans, securing election as the state’s G.O.P. governor in 2002. During Perdue’s bid for Governor he vowed to create an Inspector General’s office to investigate corruption and cronyism.

This Republican view of corruption was very peculiar. It doesn’t reside among the rich, and the powerful—the country club set who form the backbone of the Georgia G.O.P. In the Perdue view, it seemed, corruption was the province of those who but a few years ago only gained admission to country clubs as caddies and hired help. And to reinforce that point, Sunny Perdue not only traveled to Senator Walker’s hometown of Augusta to introduce this initiative, he actually held a press conference in front of one of Senator Walker’s businesses.

For the Georgia G.O.P., Charles Walker, a successful Black entrepreneur who was a political threat, and who attacked their most sacred image—the rebel flag—was the perfect “poster child.” He summed up everything they despised. The attacks on Walker reached a fever pitch when his son, Champ, secured the Democratic nomination of a Georgia congressional seat. Leading Republicans, backed-up by a right-wing fringe talk radio host, launched a hysterical campaign against a “Black family” that was seeking to “dominate Georgia politics.” Taking down the Walkers was to be an act of retaliation for their offense against the rebel flag.

Meanwhile, the Georgia Republican leadership, including now-Governor Perdue, openly pressured the U.S. Attorney to “go after” prominent Democrats, starting with Walker. In response, U.S. Attorney Richard S. Thompson began investigations targeting a large part of the state’s Democratic leadership. His targets reportedly included Speaker of the House Terry Coleman, Special Prosecutor Peter Skandalakis, Senator Van Streat, former Governor Roy Barnes and Senate Majority Leader Charles Walker.

Thompson’s political vendetta got so obvious that they drew numerous complaints. In 2002, an Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR) investigation within the Department of Justice was begun following the issuance by U.S. Attorney Thompson of a campaign season press release which launched wild attacks on then-Governor Barnes, Special Prosecutor Skandalakis, and Senator Van Streat. The Justice Department’s internal review found that Thompson was guilty of a great number of politically motivated ethics lapses, including violations of his duty to (1) to refrain from making public comment on an ongoing investigation, (2) refrain from participating in a matter that directly affected the interests of a personal friend and political ally, and (3) refrain from taking action that would interfere with or affect an election. The investigation concluded that U.S. Attorney Thompson “abused his authority and violated the public trust . . . for the purpose of benefiting a personal and political ally.”

The Republican-controlled Congress, aware of these serious charges, took no action against Thompson. To the contrary, the Georgia Republican delegation has been tightly linked to the scheme. Senator Walker’s attorneys claim that records will show that Republican Congressmen Charlie Norwood and Jack Kingston flew Thompson to Washington and pleaded with him not to resign, but rather to keep his criminal investigations against Democrats running. Thompson did resign his office as U.S. Attorney, but he reportedly promised the Georgia Republican congressmen that his staff would press ahead with its political prosecutions notwithstanding his resignation. Thompson was then appointed an Administrative Law Judge by the man who had most aggressively pressed for the criminal scheme, Governor Sonny Perdue.

The investigations of former Governor Barnes and several other officials were dropped following the OPR investigation. However, as promised, Thompson’s successor, Lisa Godbey Wood continued the investigation against Senator Walker. This investigation resulted in the indictment filed against Walker on 142 counts of mail fraud, tax fraud and conspiracy, including numerous counts related directly to his service as a member of the General Assembly. He was accused of “theft of honest services,” which is a standard prosecutorial approach to bringing federal charges against state officials accused of corruption. Following the usual pattern, the indictment was handed down at the beginning of the 2004 election season and was loudly trumpeted to the Georgia press. Walker’s daughter was also indicted, and pleaded guilty to failing to report $700 in income. This sort of behavior would normally result in a fine and would be handled on an administrative footing, but for the Walkers, the long knives were out.

Building upon the evidence gathered by former U.S. Attorney Thompson, many of the charges against Walker lacked sufficient evidence and could best be described as “stretches.” One of the most spectacular claims made against Walker was that he lied about the readership circulation of his newspaper, that he stole funds from a charity that he funded with his own money, and that he stalled a bill that would hurt his business. Although many of these charges were plainly false (for instance the bill in question was not stalled–in fact it passed session), Walker was badly damaged by the aggressive hawking of the charges, and by the great proliferation of counts. As Alexander Hamilton once stated, if a man is charged with enough wrong-doing, no matter how innocent he may be, a prosecutor can count on a conviction. At some point the jury will believe the prosecutors are bringing charges for a good reason. In the end, Walker was convicted on 127 counts and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

My take in looking over the charge sheet and the evidence is that there was some evidence to support individual corruption charges, but the charges themselves were amazingly petty. No rational federal prosecutor could have justified the tens of millions of dollars poured into the criminal investigation and prosecution launched against Walker. And no independent prosecutor exercising reasonable discretion would ever have brought charges. The evidence against Walker was trivial, the charges themselves insubstantial. What got Walker charged, tried and convicted was simple: politics. The case was trumpeted throughout the 2004 election season to advance a Republican electoral agenda and to keep the words “corruption” and “Democrat” steadily linked in the press.

The case was coordinated by and involved Noel Hillman and his Public Integrity Section. And it was pursued at the same time that the Abramoff scandal, which channeled straight into the heart of the Georgia G.O.P., was being carefully isolated to protect prominent Georgia Republicans. One was what Norm Ornstein and Thomas Mann have called the “greatest political scandal in America’s history,” and the Walker case was a petty vendetta. As the Walker case was ramping up, press disclosures linked Ralph Reed, then the leading G.O.P. candidate for Lieutenant Governor, to corrupt dealings with Indian gambling interests involving an entity he created in connection with a number of other Georgia Republicans called the U.S. Family Network. This entity laundered casino gambling money and redirected it into Republican political campaigns. The overall Abramoff scheme involved tens of millions of dollars systematically secured through fraud from Native American groups, and large parts of this money were then pumped in G.O.P. political campaigns throughout the South. A significant number of Georgia Republican leaders were implicated in this scheme. Moreover, it was clearly a matter for federal law enforcement, because it involved Native American groups, and inter-state dealings. But throughout this period, resources for the Abramoff probe were carefully limited and cordoned off, whereas prosecutorial resources were lavished on the Walker case, which involved petty state law infractions and had no obvious reason for being handled by federal prosecutors or investigators in the first place. In the end, resource allocation was the key tool used by the Bush Justice Department to achieve its political agenda.

But most importantly, the Department of Justice itself concluded on the basis of overwhelming evidence that the investigations spawned by U.S. Attorney Thompson were unethical. They had been schemed and conceived as an act of political retribution. Was the decision of Thompson’s successor actually driven by an independent reassessment of the case? The answer to that question is plainly “no.” Indeed, the evidence points to the continuous involvement of senior figures of the Georgia Republican Party in the process through the decision to continue. Following the prosecution of Charles Walker, the prosecutor who handled the case was appointed as a federal district court judge. She was recommended by Congressmen Charlie Norwood and Jack Kingston–the same Congressmen who tried to convince Thompson not to resign and made a strong push for Walker’s prosecution. Walker’s lawyers say it was a political payoff for a political prosecution.

Procedural Shenanigans

The case was assigned to Judge Dudley H. Bowen, Jr., who, according to Walker, had close ties to the Augusta newspaper which was the principal business competitor of Walker’s newspaper business. Walker did not seek Bowen’s recusal. However, Walker’s defense team filed approximately twenty-five pre-trial motions, each denied by Judge Dudley Bowen. Among the motions was a Motion to Dismiss based on Governmental Misconduct and Selective Prosecution. Not only was this motion dismissed, but a hearing was never conducted, despite the unique and questionable circumstances that spurred the Walker’s investigation—namely, the Department of Justice’s internal investigation had concluded that the accusations leveled in the motion were meritorious. In the view of many legal scholars, including the University of Georgia’s Prof. Ronald Carlson, the motion should have been dispositive—the case had to be dismissed. No other remedy for the demonstrated abuse would have been appropriate. Phil Kent, “Should Charles Walker Get Off?,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Aug. 27, 2004.

Stacking the Deck

Prior to jury selection, Judge Bowen directed that the jury pool be based not on the Augusta Division (which is majority Black) and instead directed that the pool be drawn from a pool which was 75% White, in south Georgia. This prejudiced Walker by reducing the number of potential Black jurors, and more importantly it meant that the pool would come from the white communities in which rage was been vented against Walker by the Republican Party machine—he had been identified as the man who took a stand against the Rebel Flag. The jury foreman, for instance, was a right wing Republican from South Georgia known to share these sentiments.

The procedural issue that ignited the most attention in this case was the jury selection process. In the process of jury selection, both the prosecution and defense are given the opportunity to “strike” jurors. These strikes are especially valuable in cases where prejudice or bias may easily effect a juror’s decision. In a striking departure from the normal rules which strongly prejudiced Walker, Judge Bowen seated four jurors on the jury notwithstanding the defense’s peremptory strikes. This included at least one notoriously partisan Republican elected official. In re-seating these jurors on the jury, the judge was consciously stacking the jury with individuals who looked suspiciously like the judge (namely, white, prosperous and Republican). In addition to appeals made on behalf of Senator Walker by his attorneys, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and the Georgia Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers submitted an Amicus Brief supporting the reversal of Walker’s conviction. The Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals turned down Walker’s appeal, saying that while the conduct of the trial judge was “disturbing,” it would not overturn his exercise of discretion.

Walker’s case has not only attracted the attention of several legal associations, but also the representation of famed appellate and constitutional lawyer, Alan M. Dershowitz. The Judiciary Committee will be taking Prof. Dershowitz’s remarks on Tuesday.

Leslie Fields contributed to this post. Next: Prof. Alan M. Dershowitz discusses the Walker case and what he plans to say to the Judiciary Committee about it.