Tapestry of the Baroque: Threads of Splendor, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Tisch Galleries, through Jan. 6, 2008.

For holiday season visitors to New York City, there is one exhibition to search out—the show of mostly Flemish tapestries from the period 1590 through 1720 now showing at the Metropolitan Museum.

A couple of year ago, I visited the village of Teotitlan del Valle, an hour outside of Oaxaca, where Zapotec Indians have for centuries practiced the art of weaving tapestries. I passed an afternoon watching them craft pieces with traditional geometric designs, as the most talented among them worked very skillfully with bobbins of yarn to interpret works of art on their looms. One was hard at work with a reproduction of a mural by Matisse requested by a German tourist, carefully matching colors and measuring proportions. What they did fluctuated somewhere between the artisanal and the truly artistic, and it was clearly a fading craft.

Somewhere on the road to modernity, however, the art-consuming middle class got disabused of the idea that representational art could involve threads and yarns. Instead, it seemed to require palettes and paint, brushes, chisels and mallets, canvas, stone and metals. However, a visit to this exhibition will teach you that the production of a fine tapestry in the Flemish Golden Age was very much a matter of high art. The concepts, the designs from which the tapestries were realized, were by the great artists of the age—Raphael, Peter Paul Rubens and Charles Le Brun, for instance, and the skill used to realize their designs in wool, silk and gilt-threads was dazzling.

Tapestries had of course emerged in the high Gothic age, and the Met houses some of the finest—particularly the unicorn cycle, which are worthy of a pilgrimage to see up in the Cloisters Museum at the northern end of Manhattan. The Met also mounted a major exhibition in 2002 of Renaissance tapestries, and the works that launch this exhibition could have been drawn from the last display.

But the story behind this exhibition of forty-five truly extraordinary works of art in wool and silk is one of the birth of a new level of artistry in the midst of a time of great deprivation and violence. As the religious wars arrived in the Low Countries with the armies headed by the Duke of Alba, intent on extinguishing the Protestant heresies in the north. Alba’s troops visited devastation on the region, forcing many of the great Flemish tapestry artists to flee. The exhibition begins, ironically, with a major grouping including a work that extols the military victories of Alba that produced this tapestry diaspora.

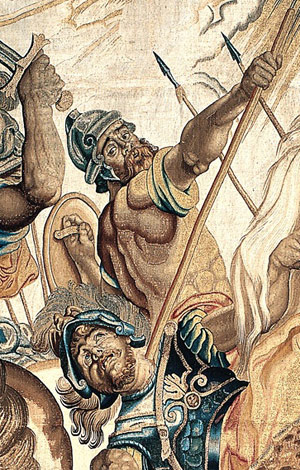

In terms of artistry, the tapestries of this period show a steady evolution from the Gothic and Renaissance images: the human figures appear bolder, more life-like and much larger. For the tapestry weavers this required the reproduction of human flesh and musculature, which were technically very demanding. They met this challenge with fascinating dexterity involving the mixture of three or more threads to cover a tiny point of skin; but they also opted for clad human figures where Rubens had chosen nudes—precisely because of the process of reproducing human flesh and muscle tone was extremely difficult and time-consuming.

This panel from a 9-piece series designed by Peter Paul Rubens on the life of the Roman Consul Decius Mus is a good example of the emergence of the larger-than-life, robust heroic figures that were unknown in earlier tapestry weaving. There is a great sense of drama in the works, but they are also of an arresting beauty. The color palette is both soothing and rich. It is dominated by a tremendous array of shades of greens, teals and blues from which the very realistic flesh tones of the warriors leap out.

The Decius Mus tapestries were still manufactured in Brussels. But most of the balance of the exhibition represents the scattering of the master artisans. One very striking tapestry comes from a studio created by Duke Maximilian in Bavaria. It is part of an allegorical series, this one depicting Night. She is a not particularly attractive woman who holds up two fingers which are lit like a torch, as is her head. The image is captivating, dramatic, and the execution is beautiful. The colors of this work are as fresh now as if they had been woven last week, and the work also makes heavy use of gilt-threads to give it a deep internal glow. The image overall looks like something from the studio of a nineteenth century English pre-Raphaelite.

Another group of Brussels artists took up residence across the Channel in the London suburb of Mortlake, manufacturing tapestries for the English crown. Some of the best tapestries in the exhibition come from this source, and one of them, which recreates Raphael’s famous scene of the Miraculous Draft of Fishes from the series Acts of the Apostles, was surrounded by gaping crowds both times I went to this exhibition. From a distance it seems hard to believe that this is something woven, it comes too close to the painter’s palette and style. The combination of the religious imagery, the extremely restrained treatment, and the luxury and hypnotic beauty of the work make me think of the famous statement of John Calvin: “let those who have abundance remember that they are surrounded with thorns, and let them take great care not to be pricked by them.”

Then we come to a collection of Gobelins tapestries, including a series glorifying the life of the Sun King. Some wonderful color in these tapestries, but beside the Biblical allegories, the works of classical history and the battle scenes, they seem a bit weak. Do look at the meeting between Louis XIV and Cardinal Chigi, though, and examine very closely the scintillating purple, mauve and red cape of the French prelate located to the left of the reception in the king’s bed chamber. It dazzles.

Wonderful to look at, but I’m not sure there’s anything here I would really want to have in my living room. Except, perhaps, for this piece close to the end of the exhibition.

This tapestry was woven on the basis of a series of sketches brought back from Africa and the Indies—exotic birds, beasts and fishes. At its center is a “striped horse” (that is, a zebra, though the artist has portrayed it just as the title implies) being attacked by a jaguar. The tapestry is a bit cramped, of course, but it’s lively, has wonderful color and detail and is simply amazing to look at—every corner in fact. The copy portrayed here is from the Museu de Arte de São Paulo in Brazil, but the one on display at the Met is drawn from the same cartoon, but is missing the hunters on either end—it actually looks even better, and the color is simply amazing.