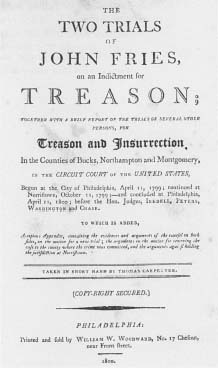

The most outlandish political show trial in American history occurred in a federal court in Pennsylvania; in fact it occurred twice. The year was 1799, and the retrial was in 1800. It was what the Pennsylvania Germans commemorate as the “Blitzwasser” or hot-water incident—so named for the kettles of boiling water that the citizens threw at federal tax collectors. The Federalist Administration in Washington had just introduced a direct house tax to help finance a shadow war it was conducting with France. But throughout the inland core of Pennsylvania—from Lancaster north to the Poconos—the population was outraged. German settlers, generally known for their Quietist tendencies, were stirred to anger for the first time. And their leader, John Fries, was plucked as a target. The United States Attorney, William Rawle, acted quickly, sending the militia to suppress a revolt. But when the militia arrived, it found there was no revolt in sight. It nevertheless seized John Fries, a former officer of the Continental Army, and brought him to Philadelphia to be tried. Four federal judges presided over the jury trials (two for each trial), and the juries, being explicitly instructed and harangued, very quickly convicted Fries. The judges then sentenced him to be executed for treason. Fries’s anti-tax rhetoric was viewed as an incitement to insurrection. The trial was designed for two clear purposes—to eliminate John Fries as a political leader, and to warn the Pennsylvania Germans that they would be dealt with in a brutal manner if they showed resistance.

Many Pennsylvanians were aghast by the entire scene, and particularly by the use of the criminal justice system to take a harsh swipe at citizens who opposed the Federalists on their tax-and-spend policies. The U.S. attorney, of course, was a Federalist. And so were both of the judges. But the judges dismissed any talk of politics. They were simply upholding the law and doing what their office required, they said. The fact that Fries was agitating for the opposition party had played no role in things, they claimed.

History has come to quite a different assessment. The Fries case, and more than two dozen others that were brought under the Alien and Sedition Acts and related legislation, are now viewed as a gross deviation from a tradition which bars the politicization of the criminal justice system. Indeed, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase was brought up on impeachment charges over his inflamed and partisan handling of the case. Thomas Jefferson, who wrote to friends of his anxiety that even he might be prosecuted, called it “the reign of witches.” It ended when the election of 1800 swept the Federalists from power. Indeed the Pennsylvania interior, which had been solidly Federalist, was converted on the strength of the Fries incident—it led the move into the camp of what would become the Democratic Party. As Lancaster and Bethlehem turned Democrat, so too did Pennsylvania, providing the margin by which the Federalists were defeated.

But the “reign of witches” is back with a vengeance. Reading newspaper accounts from Pittsburgh yesterday brought the Fries case back to mind. Sometimes history repeats itself, even in the heart of Pennsylvania. Most Americans know about the prosecution of Cyril Wecht because it has already been the subject of hearings before the United States Congress, in which the nation’s most prominent former Republican Attorney General, Dick Thornburgh—Wecht’s lawyer—raised a charge of political prosecution against U.S. Attorney Mary Beth Buchanan. In fact, Buchanan’s name has surfaced repeatedly in the investigation of the U.S. attorneys scandal—each time suggesting some element of extreme political skullduggery, often tying her to the White House and figures who have been forced to resign in disgrace from the Justice Department.

In the Congressional hearing, Thornburgh went over the litany of charges Buchanan had raised against Wecht (most of which sounded completely absurd), the timing of the charges to match election cycles, the leaking of materials about the investigation to the newsmedia—all of which raised very grave concern about the professionalism of the prosecution, and left little doubt whatsoever as to political motive. The reply of the Department of Justice was limp and unconvincing, and Congressmen on both sides of the political aisle pointed that out. On CNN’s Larry King Live, Thornburgh went into the case in greater detail, and MSNBC’s Dan Abrams followed up in his series “Bush League Justice.”

But U.S. District Court Judge Arthur J. Schwab doesn’t see things the way Congress and the media do. In fact, he refused even to do what the U.S. Congress had already done—conduct a hearing on the subject. (Incidentally, the U.S. attorney in question failed to comply with the Congress’s requests for information about the case, an act which taken all by itself suggests that she has quite a bit to hide.) Judge Schwab, whose attitude towards Ms. Buchanan can only be called solicitous and protective, dismissed the questions as a “conspiracy theory.” Judge Schwab also entered some very unusual orders providing that the jury pool be kept secret, although he pulled back from some of his more extreme positions yesterday. Wecht and his attorneys are now seeking to have Judge Schwab recused.

Surveying political prosecutions around the country, a consistent phenomenon can be observed. The cases seem somehow regularly to land in the court of a Republican judge with strong party connections, and most frequently in the court of a judge who owes his appointment to George W. Bush, the man who has done more than any president in history to politicize the Department of Justice, and the man who is in concept bringing the charges. I used to think this was just coincidence. I no longer think that.

The judge then refuses to examine charges that the prosecutions are politically motivated, and usually offers up some derisory comment. Anyone who would think that President Bush would abuse his powers for partisan political reasons must be some tin-hatted loon, apparently (though by current polls 64% of Americans think this, while only roughly 24%–including the judge–feel otherwise, they’re what are called “the base”). And the judge tends to use his quite considerable latitude in conducting things to help the prosecution at every turn. All of this adds tremendously to a sense that the court process is being infected with an improper partisan animus.

Judge Schwab refused to entertain a hearing on the charge, which is now widely accepted in the country, that the case against Cyril Wecht is politically motivated. He refused to step aside when his impartiality was challenged. He entered an extraordinary series of orders restricting the defense’s access to information about the identities of the members of the jury pool. And now on the eve of trial, U.S. Attorney Buchanan, who had just said she was ready to go to trial on 84 counts, has asked Schwab to dismiss half of them. The judge seems poised to accommodate Buchanan in her eve of trial sea change as well. This provides further serious evidence of misuse of the criminal justice process by Buchanan, showing that she has adopted the “garbage can theory of prosecuting.” As Alexander Hamilton observed, prosecutors can secure the conviction even of a wholly innocent man simply by throwing enough charges at him, since at some point the jurors will think simply because of the volume of the charges that one of them must be true.

A conscientious judge would have vetted the charges, would have looked into the pattern of media leaks, and would have conducted a proper hearing into the accusations of political manipulation. This might have led to a decision to dismiss the case and, potentially, to refer some questions to the state bar’s ethics committee or to the Justice Department’s Office of Professional Responsibility for further proceedings. Schwab did none of these things. But then a conscientious judge with a background like Schwab’s would have made one single ruling in his case–he would have recused himself from being insolved in it.

How impartial is Arthur J. Schwab? When I asked members of the Pittsburgh legal community about Schwab and his reputation, I heard two things. One is that the lawyer Arthur J. Schwab was a well-regarded practitioner, working with Pittsburgh’s two largest firms. He was viewed by his peers as a capable and effective attorney. The other is that Schwab was a deeply engaged Republican and movement conservative close to former Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum. In fact, Santorum went to bat for Schwab repeatedly, pressuring President Clinton to appoint him to the federal bench, and placing holds on Clinton nominees to provide further leverage.

More to the point, Schwab and his wife made some $24,000 in contributions to G.O.P. federal campaigns between 1994 and 2001, including sizable sums as his name was working its way up to be nominated by President Bush, based on Senator Santorum’s recommendation. He figures prominently among a list of Bush-appointee judges who gave generously to the Republican Party and its candidates just as they were being picked for the bench, according to the Center for Investigative Reporting.

Schwab’s background makes him a well-credentialed federal judge—but not a judge who could credibly be viewed as impartial in a career-bruising prosecution brought by one partisan pitbull against another: movement conservative Republican Mary Beth Buchanan against Democrat Cyril Wecht. It’s hard to observe this without thinking that the criminal justice system is not the place for it. Schwab’s conduct of the case so far reveals an unmistakable pro-prosecution bias and a dismissive attitude towards matters of grave public concern which have been raised by the defense.

If this case goes to trial with Schwab on the bench, as now seems likely, that will further erode public confidence in the fairness and independence of the federal judiciary. Schwab’s insensitivity to that point is very telling; it provides more amunition for those who view this as a political show trial in the making.