Today is December 7. This is a special day in our history, a definitional day, a day to pause and remember. On this day — “a day that will live in infamy” – the Empire of Japan attacked the United States armed forces gathered at Pearl Harbor. And on the other side of the world, December 7 was also a momentous day. The German drive on Moscow stalled — it happened at a place not far from the airport at Sheremetyevo that I drive past a couple of times each year, marked by a memorial composed of over-sized tank barriers. And in Berlin, faced with concern about the stalling effort and the approaching, life threatening Russian winter, Field Marshal Keitel issued the “Night and Fog Decree,” one of the bloodiest and most disgusting documents of a war that challenged the conscience of the world. All of this occurred on a single day sixty-five years ago: December 7, 1941. For a generation of Americans, their lives changed, suddenly and dramatically. National security had been a lingering worry. Suddenly it became a matter that dominated and redirected their lives. Americans handled this challenge with a nobility and clarity of purpose that are worth thinking about today. I propose to do just that, for a simple reason: America needs to remember its history, its values and its legacy. In a world of 24/7 cable pseudo news channels, they have gone missing. And that loss cheapens the lives of every one of us.

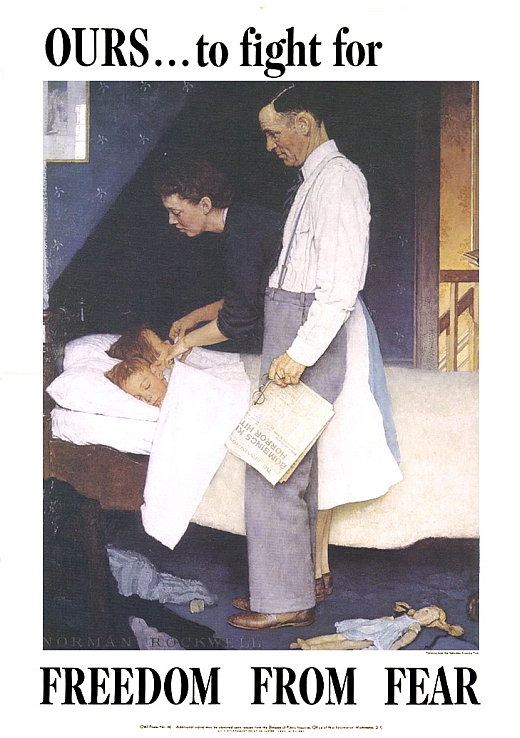

In his first inaugural, Franklin Delano Roosevelt told us that “the only thing we have to fear… is fear itself.” The Roosevelt presidency, and especially the conduct of the Second World War is the first proof of this statement. And in the last five years, Americans have lived through a second proof of it – if they only will open their eyes and see it. Those words sound simple to us today, and we need to remember the context in which they were uttered. As Roosevelt spoke, a shadow of totalitarianism had fallen across much of the world – fascism dominated the European continent and the rising Empire of Japan and communism covered the great Eurasian landmass that stretched in between them. These totalitarian regimes shared many common traits, and chief among them was the use of fear as a political tool. Fear was used to render the domestic populace silent and stupid. Fear was used to threaten and win concessions from the surviving democratic states on the periphery of the totalitarian swamp. Roosevelt understood the threat perfectly, and he understood that fear and the use of fear was the essential dividing line between the Western democracies and the totalitarian states. But somewhere along the line, this fundamental truth was forgotten in America.

In one of his earliest works, Edmund Burke tells us that fear is the hallmark of a despotic society. Fear is used to make a population stupid and subservient; it is used to chill the natural demand for the most basic of freedoms and liberties. A ruler who uses fear in this way deserves contempt, Burke wrote. One of the essential tools of fear is torture. Historical studies of the use of torture inevitably find that torture exists not as a device to gather intelligence, but as a tool to instill fear — to petrify, to silence. The Catechism of the Catholic Church understands this. It contains a single section addressing torture, and it is the same section which addresses terror used as a political tool. The Catechism teaches, and correctly understands, that torture is in its essence a tool for terrorizing a population.

This is why Roosevelt was explicit about fear as a tool, why Allied propaganda made clear that torture marked our adversaries, but not us. The Greatest Generation upheld our nation’s ideals when it went to war. It understood the value of those ideals as weapons. It won the war. And then it did some real magic. By treating our adversaries as human beings, by showing them dignity and respect, our grandfathers’ generation created a new world in the rubble of the Second World War. The nations which were our bitterest adversaries — Germany, Italy and Japan — emerged in the briefest time as our committed friends and allies. A world was born in which America was the dynamic center. And the foundation was laid to win the Cold War as well, after which America would emerge as the world’s sole superpower, its direction-giving force.

Now I’d like you to use your imagination for a second. Let’s assume the unthinkable: that America had embraced Mr. Bush’s “Program” in the Second World War; that German, Italian and Japanese fighters had been waterboarded, subjected to the cold cell and techniques like “long time standing.” Do any of you think for even a second that these nations would have been our allies and friends in the following generations? Think of how much darker, colder and more hate-filled our world would be than it is today.

I ask this question because this issue — the use of “coercive intelligence gathering techniques” — should be a matter of grave concern to everyone of us. But it has taken time for the question to be asked and discussed. And for that, I have a bone to pick with our media. By mid-2002, evidence began to collect that highly coercive techniques were being used in Guantanamo and in Afghanistan. A few brave souls reported on this — Dana Priest and a couple of her colleagues at the Washington Post were among the first, and there were stories in a handful of other newspapers. I have spent some time talking with print media reporters and editors about this process. What I learned was not encouraging. There was strong pushback from the beginning. Editors did not want to run these stories. Many stories were spiked. And when they ran, they were cut back and appeared buried deep inside the paper. Why? Journalists were under immense pressure at this point, from the Pentagon, the Administration and from the rightwing chorus that dominates much of the cable news world. Threats were raised: papers that report such matters are slandering our troops, it was said. They are undermining our combat morale. They are weakening our war effort. But my recapitulation here hardly does justice to the ferocity of some of these attacks. In sum what happened? The press was intimidated into a process of self-censorship.

I don’t believe this process continued indefinitely, but some disturbing traces continue. In April 2004, the photographs that Joseph Darby circulated out of Abu Ghraib broke in The New Yorker and CBS’s 60 Minutes, and a thaw began. The media discovered the issue, and quickly discovered that it had links with important policy decisions taken at the top of the Administration. Curiously, the media long gave equal billing to increasingly absurd explanations offered by Administration apologists. But with time they faded.

When we talk about torture today, Abu Ghraib seems a synonym. But this is deceptive. In fact all those wretched photos show is humiliation tactics. They are grim and disturbing. They make a mockery of standards laid down by George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. But they’re hardly the worst of the tactics employed. Ninety-eight deaths occurred in detention in circumstances suggesting foul play. Perhaps two dozen of them can be linked pretty directly to torture. This includes severe beatings, waterboarding, and severe stress positions — curiously, all tactics that we associate with torture from the middle ages, definitional torture — as well as alternating extremes of heat and cold, long-term sleep deprivation. We can talk about these techniques in a clinical sort of way, but in the end it is a question of mixing and alternating, a question of destroying the human material in captivity, of destroying humanity.

The media had a role in this process — it was to keep us informed about what is being done in our name. For two years, the media failed us miserably. More recently it has started to make up for its failings. But the process by which the media was silenced is troubling, and it, too, is something we should think about.

The key tool used to silence the media was simple: the patriotism of journalists who wrote critical articles was systematically challenged. There is an irony about this that I find remarkably unsubtle. There is nothing unpatriotic about criticizing the use of highly coercive techniques. They have put Americans in uniform in grave risk — and they will continue to do so for a generation at least. They have done incalculable damage to our nation’s honor and reputation. They have dramatically undermined our ability to be a moral leader in the world, to forge and sustain alliances — alliances which could save the lives of thousands of Americans in future conflicts. Our Founding Fathers understood these principles perfectly, which is why the notion of humane warfare were an essential part of the beacon they fashioned. So I ask you: who demonstrates patriotism today – the critics who stand fast by our foundational values? Or those who would ignore our traditions by reaching quickly for the base and the brutal? No real patriot today, no citizen who is concerned about the fate of our fellow citizens in uniform, can be silent on this issue.

A short time ago, in Germany, I spoke with one of the senior advisors of Chancellor Angela Merkel. I noted that a criminal complaint had been filed against Donald Rumsfeld and a number of others invoking universal jurisdiction for war crimes offenses. How would the chancellor see this, I asked? There was a long pause, and I fully expected to get a brush-off response. But what came was very surprising. “You must remember,” said the advisor, “that my chancellor was born and raised in a totalitarian state. She cannot be indifferent to questions of this sort. In fact, she views them as matters of the utmost gravity and they will be treated that way. The Nuremberg process happened in my country. It was painful for us. But we absorbed it. It became a part of our legacy. An important part of our legacy. We will not forget it. But I have to ask you: why has your country forgotten?”

That is a question to reflect upon on this day, on December 7. The time has come to remember.

Remarks delivered at the Wolfson Center, New School University, New York City, Dec. 7, 2006

Post Script

I delivered these remarks last year, and we now assign to December 7 yet another meaning: On December 7, 2006, as I was speaking at the New School, Bush’s Attorney General, Alberto Gonzales, was acting to dismiss seven U.S. Attorneys as a part of a Rovian master plan for the politicization of the Justice Department. It was another sneak attack–this time against the Constitution, the Rule of Law and on one of the most important institutions of our Government, the Justice Department. It was simultaneously an attack on a group of federal prosecutors marked by integrity and zeal, and an attack on the concept of integrity as an aspect of the office of federal prosecutor. One year later, this attack has still not been repelled. December 7 is a day to commemorate American values, and especially one of the cherished Four Freedoms: the Freedom from Fear, and from politicians who would wield fear as a political tool. Happy Freedom from Fear Day.