Washington Irving, The Alhambra (1832) in: Bracebridge Hall, Tales of a Traveller, The Alhambra, p. 849 (Library of America ed. 1991)

There are some writers whose works seem to serve perfectly for reading during the Christmas season. Charles Dickens, of course, may count first in that number, and indeed the Christmas tale is something he consciously pursued, with notable commercial success, as a genre. But turning to the American literary canon, I’d pick Washington Irving. Moreover, the fact that Irving is so neglected these days is a bit shameful. Irving was the nation’s first literary star; the first American to be accepted as an equal by the likes of Coleridge and Scott, Tieck and Lamartine. And there’s really no doubt, he was their equal, if not indeed their superior. He’s a heart-warming writer, relentless in the pursuit of knowledge, but never losing his human bearings in the process. In Dickens’s novels we note the occasional appearance of the kindly figure with a heart of gold and an instinct for charity. But Washington Irving is himself that figure, and his writings are the gift he offers up.

The books may be a bit musty from nearly two hundred years of wear. But reading his books is like having a fireside dialogue with a friend, on some cold and wintry evening in a cozy cottage. One cottage in particular comes to mind: if you’re ever in New York’s Hudson Valley and have a moment, the spot to aim for is Sunnyside, Irving’s charming little house on the river, now in Tarrytown. He built this perch late in life, and due to the encroachments of family to whom he was unstintingly generous, it was never quite as comfortable a retreat for himself as he imagined. But it is also an immediate extension of the writer’s persona. He designed it, and the house is as much an expression of Irving as one of his tales.

The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon is of course the classic collection of Irving’s tales, with pieces like “Rip Van Winkle” and the story of the headless horseman, and I love it, but the work I came later to absorb and admire most is The Alhambra. It is a story of the confluence of cultures—a European settler from the New World visits the Old. He spends years on the continent, coming ultimately to rest with a diplomatic charge in Spain. But while there, he discovers the ultimate gembox of Europe. And its essence is not of Christian Europe, but of Muslim Andalusia. This book is a work of exploration, historical narrative, and flights of Romanticist fantasy. It is exotic and also very humane. And its motto may as well be the one that Irving affixes to Bracebridge Hall:

Under this cloud I walk, gentlemen; pardon my rude assault. I am a traveler, who, having surveyed most of the terrestrial angles of this globe, am hither arrived to peruse this little spot.

Irving’s writing from and about Spain is subject to a recurrent critique, namely that it suffers from orientalism in the sense used by Edward Said. It is argued that he presents a rather two-dimensional picture of the Iberian peninsula’s Islamic past, that he shows the foibles and weaknesses of the Muslim rulers and chronicles the inevitability of the Western Christian reconquista that would bring Muslim Spain to an end. I am puzzled by this criticism, because I think this has it exactly backwards. Irving is creating a romance for a golden age in which three distinct cultures enriched the Iberian peninsula. He portrays each of these cultures as noble, fruitful and important in its own way. The new culture which has arrived in its stead is suffocating, intolerant and uncreative, a dim reflection of something which was once great.

It is true that Irving does not train a historian’s eye on his subject; he is a man of the community of letters, not a historian. He wants to invite attention, inspire interest in the hope that human interest, once aroused, will explore further. The idea that Irving’s view of the Muslim tradition of Spain is condescending or denigrating is, to me, simply baffling.

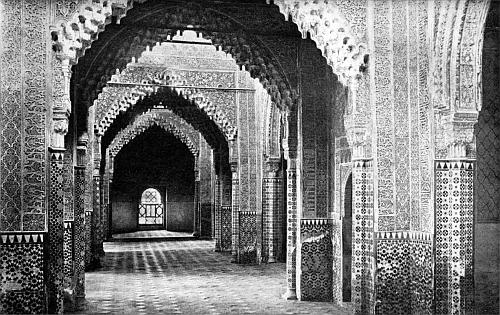

The Alhambra is a work about an architectural relic, of course, but it would be more accurate to say that Irving uses the Alhambra as a physical place, as a departure point for explorations that shift from the current day (i.e., the early nineteenth century) back to the Alhambra’s founding. Nevertheless, the Alhambra itself takes on personal as well as artistic and philosophical attributes. In introducing his work he has taken care

so that the whole might present a faithful and living picture of that microcosm, that singular little world into which I had been fortuitously thrown; and about which the external world had a very imperfect idea. It was my endeavor scrupulously to depict its half Spanish half Oriental [there’s that dreaded word] character; its mixture of the heroic, the poetic and the grotesque; to revive the traces of grace and beauty fast fading from its walls; to record the regal and chivalrous traditions concerning those who once trod its courts and the whimsical and superstitious legends of the motley race now burrowing among its ruins.

The exercise antedates Irving’s service as minister (i.e., ambassador) to the Spanish Court. It goes back to 1829, when he was traveling in the company of a Russian diplomat. He sets out from Madrid, across the plain of Castile, and finds a topography, especially after he passes through the ancient capital of Seville and approaches Andalusia proper, contrary to his expectations, “noble in its severity,” he says—but remarkably not very European. “The country, the habits, the very looks of the people, have something of the Arabian character,” he writes.

The perspective that he takes on Granada is Romanticist, of course, but it reminded me strongly of one specific point of reference in German literature. In the decade before the appearance of the Alhambra, there was a struggle in the literary world in Germany—a struggle over religion, state and culture. The Religious Right of the day was composed of a group of writers who saw the Christian Middle Ages as a sort of golden age. They mourned the loss of a unison of state and church, they condemned the increasing secularization of society. There was a particularly Catholic tendency in this group, though its adherents were not all Catholic. But there was a countercurrent within the Romanticist camp, one which was marked with wit, insight, irony and a healthy contempt for religious bigotry. Heinrich Heine was its greatest master, and he turned to Andalusia for a competing model.

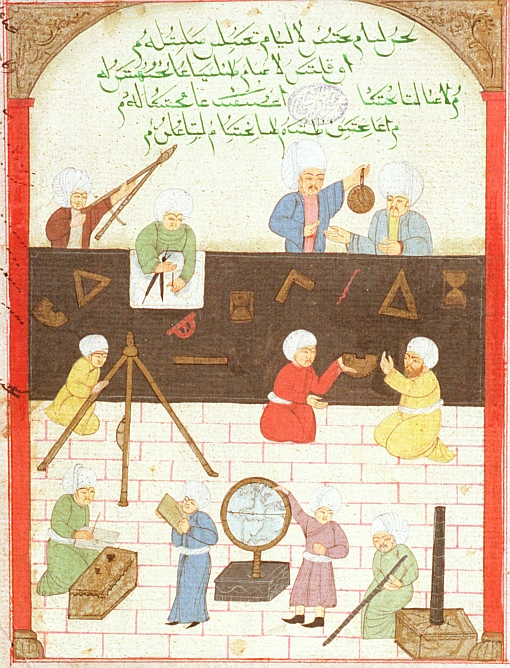

In the Middle Ages, Heine noted, the great cultural blossoming had not been in the spiritual communities of the north. It had been in the Muslim underbelly of Europe, and specifically in Andalusia. There science and learning had flourished, laying the foundation for the European rediscovery of the classical texts which occurred in the twelfth century. Two more things were appealing to Heine about this epoch. First, this was a period in which the Jewish community was permitted to exist with few impediments, and occasionally with great influence. Judaism, Christianity and Islam existed side by side on the Iberian Peninsula, and the experiment was a remarkable success. Second, this experiment failed as the result of religious fundamentalism—first fanatical Berbers sweeping into the Muslim community, and then a spirit of intolerance and reconquest capturing the imagination of the Christians in the North. The Jewish community, trapped between these waves of religious bigotry and hatred, suffered terribly. Heine developed all of this in a memorable work, Almansor, in 1823. In its most haunting lines, he reminds us that societies that start by burning books, end quickly by burning people as well. (“Dort wo man Bücher verbrennt,/verbrennt man auch am Ende Menschen.” line 243).

Irving actually spent 1823 in Germany, studying German language and literature, and it’s a reasonably safe assumption that he read and discussed Almansor. The traces of Heine’s thinking are evident at many points.

So now to come back to Irving and the “orientalism” charge. The critics usually point to one particular tale from the book, which is, in fact one of the best constructed and most important chapters, “The Legend of the Arabian Astrologer.” This involves a Granadian king named Aben Habuz, who draws on the power of a great magus, called here the “Arabian astrologer” to contrive a defense for his realm. The defense is a magical-mechanical tower which the magus constructs. It detects the approach of menacing enemies through the mountain passes and when activated, it will stir discord in the enemy camp and thus bring their assault to an end. The device performs brilliantly, and the king is elated, offering the magus a reward of his own choosing. A Christian princess is captured in one of these assaults, and the magus lays claim to her, but the king rejects his claim, being also smitten by the woman—who is, it seems, also an enchantress.

Now the “Orientalist” critique sees in this a typical pattern. The Muslim society is lazy, self-satisfied and vulnerable. The Christian princess represents the virtues and power of the new society and way which is clearly stronger and superior and will prevail. The story reflects the process of the reconquest of Granada by the Christians of the north. The Christians are morally superior, technologically more sophisticated and this ultimate triumph is inevitable. The “Orientals” are colorful, quaint, corrupt and weak. They are destined to be trampled into oblivion or servitude by the train of time. I am reducing this critique to something of a cartoon, of course.

The truth is that Edward Said’s notion is a very powerful tool to use for the dissection of much of the literature of nineteenth and early twentieth century Europe. It does help expose the imperial lie very effectively and helps us understand how the subjugation of colonial peoples is reconciled intellectually.

But this tool doesn’t work with Irving’s piece—because his writing is working in just the opposite direction. First, anyone who’s read the Alhambra with some care can’t escape the fact that the Muslim kings and leaders—while doubtless something of a mixed bag—consistently gain the strongest praise. They are the guardians of a noble vision. They are the source of an appealing notion of chivalry. They introduce notions of fundamental justice in their treatment of other, non-Muslim peoples. The truly heroic figure of this work is Mohammed ibn-al-Ahmar, the founder of the Alhambra, whom Irving quotes repeatedly, both in Castilian and in Arabic, and whom he portrays as a model ruler.

He organized a vigilant police, and established rigid rules for the administration of justice. The poor and the distressed always found ready admission to his presence, and he attended personally to their assistance and redress. He erected hospitals for the blind, the aged, and infirm, and all those incapable of labor, and visited them frequently; not on set days with pomp and form, so as to give time for every thing to be put in order, and every abuse concealed; but suddenly, and unexpectedly, informing himself, by actual observation and close inquiry, of the treatment of the sick, and the conduct of those appointed to administer to their relief. He founded schools and colleges, which he visited in the same manner, inspecting personally the instruction of the youth. He established butcheries and public ovens, that the people might be furnished with wholesome provisions at just and regular prices. He introduced abundant streams of water into the city, erecting baths and fountains, and constructing aqueducts and canals to irrigate and fertilize the Vega. By these means prosperity and abundance prevailed in this beautiful city, its gates were thronged with commerce, and its warehouses filled with luxuries and merchandise of every clime and country.

By contrast, the Christians of the north come across pretty poorly. They are dirty, uneducated, uncouth and unpredictable. There are some noble standouts, but a lot of questionable characters.

And the “Orientalist” critique misses the point of the “Astrologer’s” tale. It also misreads the story. The Christian princess is an enchantress, of course, but she is not the king’s unmaking. To the contrary, the princess’s magical powers are not a match for the titular character, the astrologer. The king makes a bargain with him and he fails to honor it. And the astrologer reacts by seizing his prize and disappearing to a subterranean world.

This is a story with a point, it is not designed merely to entertain. But the point is certainly not about the superiority of the Christians of the north. Indeed, that notion would seem thoroughly contradicted. The princess’s army is brought into discord and easily defeated, of course. The point is evident from contrasting Aben Habuz with the founder of the Alhambra. Irving tells us that the subject of this tale is “superannuated,” “languished for repose.” He has gone lax in his duties to his people, turning to magic instead of diligence in administration and arms. (This Irving calls “honest,” the work of the astrologer, he tells us, is “cabalistic and unreliable”).

To add to the chagrin of Aben Habuz, the neighbors whom he had defied and taunted, and cut up at his leisure while master of the talismanic horseman, finding him no longer protected by magic spell, made inroads into his territories from all sides, and the remainder of the life of the most pacific of monarchs was a tissue of turmoils.

The themes here are taken from the core Romanticist roster. Magic appears and weaves its way through the plot, but he who seeks and uses it is undone by it. And in this case, “magic” stands stead for technology. Note that the magus is called a physician, an astrologer—he is a magician, but also a man of science. The distance between the two is, from the medieval perspective, slight. So the modern reading might be a little different—Irving warns of reliance too much on the marvels of science and technology. This is, he tells us, no compensation for the traditional virtues. A ruler who fails in them will be a failure as a ruler. Now that’s a lesson for the military conquerors of a more recent vintage.

But the magic, the knowledge, the technology which play such tricks in this tale are not a badge of superiority from the Christian north—rather, just the opposite. It is the Muslim world which laid claim to the secrets of antiquity, which carefully transcribed and studied them. It was the Islamic world that transmitted the seeds of modern science to the world. And this work is focused on that process.

The greater message of this work, though, is not despair, but of hope. The Alhambra stands as a monument to the great and noble things that man can achieve, and it stands as a reminder to the Spaniards of today that a culture that preceded theirs was brilliant, noble, and–perhaps—superior. But the stress remains on hope, and Irving, defying the English-only pestilence which sullies our landscape today, chooses to write it not in English, but in Spanish:

¡Que angoste y miserabile seria nuestra vida, sino fuera tan dilatada y espaciosa nuestra esperanza! — How straitened and wretched would be our life, if our hope were not so spacious and expansive!