Zwei Menschen gehn durch kahlen, kalten Hain;

der Mond läuft mit, sie schaun hinein.

Der Mond läuft über hohe Eichen;

kein Wölkchen trübt das Himmelslicht,

in das die schwarzen Zacken reichen.

Die Stimme eines Weibes spricht:

Ich trag ein Kind, und nit von Dir,

ich geh in Sünde neben Dir.

Ich hab mich schwer an mir vergangen.

Ich glaubte nicht mehr an ein Glück

und hatte doch ein schwer Verlangen

nach Lebensinhalt, nach Mutterglück

und Pflicht; da hab ich mich erfrecht,

da ließ ich schaudernd mein Geschlecht

von einem fremden Mann umfangen,

und hab mich noch dafür gesegnet.

Nun hat das Leben sich gerächt:

nun bin ich Dir, o Dir, begegnet.

Sie geht mit ungelenkem Schritt.

Sie schaut empor; der Mond läuft mit.

Ihr dunkler Blick ertrinkt in Licht.

Die Stimme eines Mannes spricht:

Das Kind, das Du empfangen hast,

sei Deiner Seele keine Last,

o sieh, wie klar das Weltall schimmert!

Es ist ein Glanz um alles her;

Du treibst mit mir auf kaltem Meer,

doch eine eigne Wärme flimmert

von Dir in mich, von mir in Dich.

Die wird das fremde Kind verklären,

Du wirst es mir, von mir gebären;

Du hast den Glanz in mich gebracht,

Du hast mich selbst zum Kind gemacht.

Er faßt sie um die starken Hüften.

Ihr Atem küßt sich in den Lüften.

Zwei Menschen gehn durch hohe, helle Nacht.

Two figures pass through the bare, cold grove;

the moon accompanies them, they gaze into it.

The moon races above some tall oaks;

No trace of a cloud filters the sky’s light,

into which the dark treetops stretch.

A female voice speaks:

I am carrying a child, and not yours;

I walk in sin beside you.

I have deeply sinned against myself.

I no longer believed in happiness

And yet was full of longing

For a life with meaning, for the joy

And duty of maternity; so I dared

And, quaking, let my sex

Be taken by a stranger,

And was blessed by it.

Now life has taken its revenge,

For now I have met you, yes you.

She takes an awkward step.

She looks up: the moon races alongside her.

Her dark glance is saturated with light.

A male voice speaks:

Let the child you have conceived

Be no trouble to your soul.

How brilliantly the universe shines!

It casts a luminosity on everything;

you float with me upon a cold sea,

but a peculiar warmth glimmers

from you to me, and then from me to you.

Thus is transfigured the child of another man;

You will bear it for me, as my own;

You have brought your luminosity to me,

You have made me a child myself.

He clasps her round her strong hips.

Their kisses mingle breath in the night air.

Two humans pass through the high, clear night.

—Richard Dehmel, Verklärte Nacht first published in Weib und Welt (1896)(S.H. transl.)

Listen to Arnold Schönberg’s stunning instrumental realization of this poem in his sextet for two violins, 2 violas and 2 cellos, “Verklärte Nacht,” op. 4.

Richard Dehmel is an important figure of the German Symbolist period, associated with the aesthetics of the Jugendstil, but hardly known in the English-speaking world. His poetry is inventive and pushed the boundaries of the stifling morality of the Wilhelmine period that Nietzsche ridiculed so brilliantly. This may, thanks especially to Schönberg, be his best known work. It was published in a poetry collection from 1896 that also included Venus Consolatrix, whose erotic language was sufficient to rouse the censors. Richard Strauss, Max Reger, Kurt Weill and Alma Mahler-Werfel all also composed his poems as Lieder.

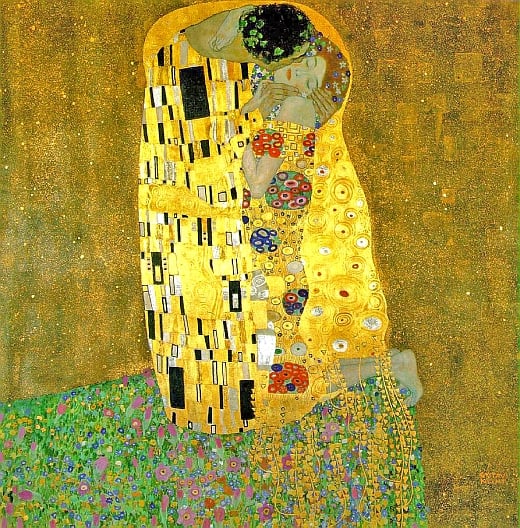

I have always thought that Gustav Klimt’s Der Kuß (The Kiss) (1907-08) was also inspired by this poem. Indeed the ties to it are very powerful. This may be Klimt’s best known painting, executed in an audaciously conceived manner. It does not reproduce well, and if you’re in Vienna, it is worth the trip to the Österreichische Galerie in the Belvedere Palace to see it. The background is a pale but complex metallic field which looks like bronze, with bursts that appear to signify stars, while the field surrounding the couple embracing is dazzling gold leaf. The masculine figure is decorated with austere black-and-white rectangles, while the female figure is covered with patches that look like millefiori Venetian paperweights, a profusion of springtime colors. The dramatic stylization of the surroundings contrasts sharply with the natural, highly erotic posture of the central characters. This seems a very conscious realization of the poem’s mysterious central line: “wie klar das Weltall schimmert!” (“how brilliantly the universe shines!”) The kiss itself is a representation of the poem’s final lines. The kiss is a passage of breath between two souls, an exchange which melds into the night air itself. This is the most enduring and fascinating of the transformations which are the poem’s subject, as well as Klimt’s painting and Schönberg’s strangely passionate music. Dehmel’s, Klimt’s and Schönberg’s works each stand alone and can be appreciated in their own right. Together, however, they make up a Gesamtkunstwerk in which the same thematic material is worked with equal genius in poetry, representational art and music.