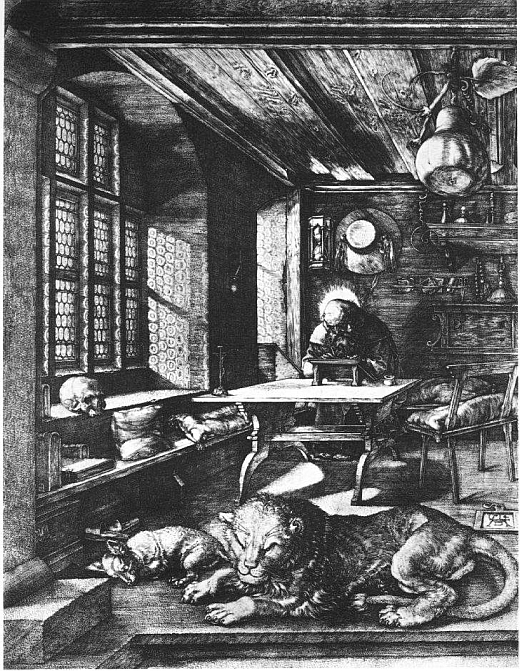

Albrecht Dürer, St. Jerome in his Study (1514), Vier Bücher von menschlicher Proportion (1528)

When I’m feeling overwhelmed, depressed, burdened with a thousand things that I can’t juggle fast enough. Or when I’ve got a headache that leaves me unable to think properly. I have a retreat. Sometimes I put on some music, something by Bach for the keyboard—maybe the English suites, performed by Glenn Gould (you need one of those recordings in which Gould can be heard, unmistakably, humming to himself in the background, the sign of the ultimate guru). But the eye also seeks a place to which it can escape, an aethereal space. And from my college years, I always found myself coming back to the same space, a place powerfully suspended in space and time, the product of a very great artistic imagination. It is this space, St. Jerome in his study, in the drypoint by Dürer.

There is something sublime about it. The resolution of endless contradictions. The space is empty and monastic—but it is warm and filled with life. It is regular and geometric—but it is an awkward medieval cubicle. A man sits in solitude—but he is not alone, he is busy, and at the same time profoundly at peace. It is a strange interior space. While its trappings are familiar, one nevertheless has the immediate sense that the “interior” here sits beyond the vanishing point in the picture; it is inside of St. Jerome. The world and its bothers fade away. It is a perfect expression of art, a place to visit with the eye and the mind.

Dürer stands out in the history of art in many ways. He seems to be a bridge, bringing Italian notions of humanism, classical learning, the rules of perspective and the portrayal of the human form, up over the Alps and into the Teutonic miasma of the north. He began his life as an apprentice goldsmith, and he ended it as a celebrated master, a man who spoke as an equal (or nearly so) with scholars, clerics, bishops and even the emperor. He thus marks the ascent and recognition of human genius. But there is also an unmistakably Gothic, late medieval element to his work, something brooding and ponderous. Through all of this one of the endearing qualities of Dürer is his relentless self-promotion. I first became conscious of Dürer staring at his self portrait that hangs in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. It was a very fine composition, hypnotic even. He, the son of a goldsmith who started his life with the jeweler’s trade, had carefully worked tiny strands of gold leaf into his own hair. Was this vanity? Experimentation?

I started reading Dürer, his own theoretical works. There, I found some answers: there was the notion of the Gegen-Gesicht an idea of visual confrontation, an idea touching reality. Were we modern viewers to look at this self portrait and imagine the picture a mirror, with Dürer himself standing in the room? That’s what the idea suggests to me–it was an artifice for the suspension of time. Then I read the poignant journal of his trip, late in life, to the Netherlands. He sees the humanistic vision which is building there, and its potential to enrich life and art; he stands at the threshhold. And in the background, his concerns about religion–the rise of the reformation, of Martin Luther, the justice of his criticisms, concern for the church, concern about others who matter to him (Erasmus certainly) who were too slow to embrace the reform cause. He has a vision of a great human tragedy to come in its wake–of the wars of religion that would decimate the continent.

Then I came across Panofsky’s book, a treasury of learning, and Weber’s, with its meticulous guide to understanding the imagery that fills the Dürer prints. I read a silly German biography of the late nineteenth century, making out Dürer’s Teutonic character—hysterical stuff, since Dürer was, of course, a Hungarian (his father, also called Albrecht, had emigrated from a small Hungarian town, and had Germanized the family name). And Hesse’s lyrical novel, Narziß und Goldmund, in which Dürer was carefully but counter-historically portrayed as an itinerant artist and counterpoised against a monastic figure who represented the vita contemplativa, a figure drawn directly from the drypoint of St Jerome! Each step let me understand a bit more, but the mysteries remained, as was of course intended. In real art the meanings must unfold over time, the process can never end.

So almost every time I came back to stare at this work, I saw something different, something new, something that I did not recognize on previous visits. And when I look at this masterwork today, this is what I see. At the center, St. Jerome, a cardinal (as we see from the cardinal’s hat hanging on the wall behind him), yet wearing not sumptuous robes of satin but a monk’s simple habit. He sits engrossed in scholarly work, a quill in his hand, a book open. He appears in a beatific aspect in two ways; the light pours through a pollard window covering his shoulder, arm and forehead (the natural aspect) with light, but independent of this, an aura surrounds his head (the contrived aspect), precisely at the vanishing point. This is an interior scene, of course, but at its heart it points to a second interior, right at the vanishing point, namely Jerome’s meditation, a world of the mind, of the human spirit seeking the divine. It is important of course to mention Jerome’s work. It is the production of the vulgate Bible from the original Greek, Hebrew and Aramaic texts. This, it is accepted, was very largely Jerome’s work. Of course it could give no offense to the ecclesiastical authorities of the day to celebrate so great and highly respected a church father. But Dürer has even here an interior message: he is reminding us that the Bible which the Church seeks to defend and hold in one text is in fact itself merely a translation, with flaws (we’ll come to that shortly) and of course, the devoted work of translation would in approaching years quickly remind Dürer’s contemporaries of another monk, with whom the artist had unmistakable affinities: Martin Luther.

Of course, we know the character is Jerome by many markings, like the cardinal’s hat, but also the lion slumbering, his symbol, and also by the strange gourde that hangs from the ceiling, with a vine and a leaf, what looks like a spray of ivy attached to it. This is the interjection of a bit of humor, for the great scholar Jerome is known for one horrible failing, which was the mistranslation of the word gourde from Jonah – he had rendered it as “ivy.” (All of this was current to Dürer; his friend Erasmus was finishing a translation of Jerome’s writings, and was reflecting on his both irksome and trivial mistake).

What can we say of the room? It is supposed to be a monastic cell, a tiny cubicle. Perhaps it is. But an amazing trick has been played with perspective; we are looking through the wall at one end of the cell, and the result is that it seems capacious, not cramped. But is it really a cell? It has more the appearance of what in German would be called a Stube, a social room, and an atmosphere which matches the German word gemütlich, comfortable or cozy. If you have traveled to Nuremberg and seen the reconstructions of the old city, or if you’ve been to Rothenburg, for instance, then you know the style here. It matches a German inn, or a Patrician home. The enormous pollard window for instance—leaded panes which look like the base of a bottle—marked an affluent dwelling, for only the wealthy few could afford such a thing. The same can be said about the architectural details, which bespeak elegance, wealth. There is a stark symmetry in all of this; it is both rigorously symmetrical and irregular at the same time (the ideal and the natural). It’s especially worth taking some time to study the exposed rugged beams in the ceiling, which demonstrate this point perfectly. At first they seem to be a series of very fine straight lines—part of a draughtsman’s scaffolding constructed within the picture to help demonstrate perspective—but as you scrutinize them more closely you see that nature’s irregularities intervene. The straight lines are never actually perfectly straight; there are even knots and irregular graining worked carefully into the beams. This is a demonstration of Dürer’s art—what seems simple and man-made turns out to be infinitely complex and of nature; though of course it is simple and man-made in the end. But this reflects the core esthetic principle of Dürer’s work. As he put it in the Unterweysung der Messung (Instructions on Measurement): “And you must know, the more accurately one approaches nature by way of imitation, the better and more artistic your work then becomes.”

But other things here speak wealth, not poverty. The furniture, a writing table and two chairs, while simple to our eye today, would be very elegant and refined for the early sixteenth century, and indeed they reflect a very high aesthetic, what we might call the integrity of simple things. Also note the pewter artifacts on the wall bracket—candlesticks, lamps, scissors, a becher, an inkpot, an ewer. Even a pair of slippers can be found, close to the bench, placed in a perfect intersection that adds to the geometric harmony of the overall composition. All of these things bespeak comfort–not opulence, but the sort of artifacts that could be associated with the “arrived” middle class, the class of artisanal masters and patricians, the class to which Dürer himself had gained entry and then transcended.

This image is thus a celebration of the human comfort that the artisinal class can produce–the work of cabinet makers, of lead-window makers, of pewterers, bookmakers. (The English language here notably fails in some ways to strike the right note. In German, each of these words would incorporate the word “Meister” as an element, indicating the highest level of the artisinal, a small step at most short of the level of the artist.) So Dürer is paying tribute to the class from which he had emerged. Though this of course is the minor tribute, for the major one is to St. Jerome and his patient, steady scholarship, opening the truth of the sacred word to a larger public through the process of translation.

Three objects convey the message memento mori, be conscious of your life, it is precious and fleeting: an hourglass, a human skull, a crucifix. Books are left on the bench, as are a great number of cushions. Again a signal of simple comforts. (Dürer loved to draw cushions. “They are shape, form, waiting to emerge. They present the plastic possibilities of life,” he writes. Here they are casually strewn about. But that is an illusion, their presence is carefully calculated.)

And finally in the foreground are two animals, a dog and a lion resting peacefully. They serve a function of course, to identify Jerome, and the dog adds to the serenity of the environment. But Dürer relishes the depiction of animals, the more exotic, the better. (Remember, this is the man who never saw a rhinoceros, but compiled a fantastic woodcut of one strictly from written accounts; the man who painted a hare so realistic that it could pass for a photograph. For Dürer the convincing reality of human depiction must be matched by realism in the reproduction of animals, which seem often to have a role no less important than the humans in the final composition.) In the Journal of a Trip to the Netherlands, he writes with childish glee of hearing that the sea had washed up a whale. He disappeared for several days, sketching the details of the whale, its skin, eyes, teeth, fins. And later again, he bargains frantically in the market at a seaside village for the cadaver of a sea lion, and spends days examining and sketching the fish and crustaceans hauled out of the ocean’s depth. For Dürer this was evidence of the bounty and marvel of nature, proof that the human form and humanity were not the beginning and the end of nature, but an important, a central part of a continuum.

But we’re paying too much attention to details, aren’t we? The power of this work lies in the spell of serenity that it casts. It creates the ultimate interior space, and it does this using ordinary rules of perspective and a conventional approach to composition. But it transcends all of that. This is a very great masterwork.

And it is also about a process, namely extraction from nature. In the greatest of Dürer’s theoretical texts, there is one brief passage that flies off the page.

Denn wahrhaftig steckt die Kunst in der Natur, wer sie heraus kann reißen, der hat sie.

Truly art is firmly fixed in Nature. He who can extract her thence, he alone has her.

This may be seen in many of Dürer’s works, and I think immediately of the great clump of earth he portrayed amazingly in a watercolor, or his hare. The objects strewn about the study are of course, extracted from nature in two respects, they have been harvested, crafted, wielded into shapes and forms for human use. But we are also seeing not the true objects, but an artistic representation of them. But that’s the least of it. St. Jerome in his study reflects a second aspect of the same conception: he is extracted from nature, in the sense that he has pursued a life of learning, contemplation and scholarship–the vita contemplativa. Dürer does not deride or diminish this. He sees something infinitely noble, powerful and inspiring in it. He calls it “Kunst,” or “art.”

But we should keep in mind that this word, both the German and the English, had a somewhat different sense as uttered around the year 1500 than today. They would more easily, more immediately, be understood as refering to a “way,” or a “style” of behavior or life. Dürer’s writing can be understood against the modern sense of the word “Kunst,” but equally against the more archaic sense. And both work perfectly in this sublime portrayal of St. Jerome.

Panofsky and Weber say this engraving needs to be understood jointly with two others–Melencolia I and the Knight, Death and the Devil (the three works known in German as the Meisterstiche); they document a number of instances in which Dürer gave copies of all three as gifts, and a few instances in which St. Jerome was paired by Dürer with Melencolia I. They say the three etchings reflect three aspects of the human condition. St. Jerome is a portrayal of the vita contemplativa, the life of the spiritual scholar; Melencolia presents the life of the secular artist or scholar; the Knight is the notion of the Christian living the vita activa. I am sure these interpretations are correct, but I see no reason why St. Jerome should not be appreciated as something entirely self-standing. It is stylistically quite distant from the other two, and to me a work of indubitable perfection, unlike the others (or perhaps I merely fail to appreciate as well the other two). And I’m less persuaded about the purely religious aspect of the three works, though the imagery is unmistakable. The works cannot be understood without an understanding of theology and religious imagery, but, conversely, that does not explain their totality.

Dürer writes:

Dieweil ich nun in keinen Zweifel setz, ich werde allen Kunstliebhabenden und denen, so zu lehren Begierd haben, hierin einen Gefallen tun, muss ich dem Neid, so nichts ungestraft lässt, seinen gewöhnlichen Gang lassen und antworten, dass gar viel leichter sei ein Ding zu tadeln dann selbs zu erfinden.

“While I have no doubt that I do a favor to all art lovers and to those who seek to learn, I nevertheless leave it to envy, which leaves nothing unpunished, to follow its normal course, and answer that it is necessarily much easier to criticize a thing than to invent it.”

But what could one find to criticize in a work like this, which comes so close to whatever perfection humans can achieve in this artistic medium? I was given no artistic talent, only a thirst to experience art by trying to understand it. The effort to understand cannot be compared with the joy of artistic creation, of course, but it brings its own rewards, even as it can never lead to a full understanding. And besides, it does a terrific job curing headaches.