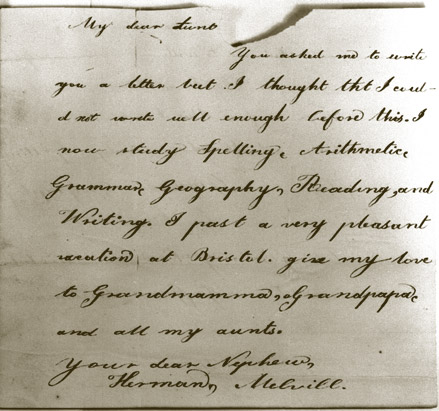

—Herman Melville, “The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids,” Harper’s Magazine, April 1855

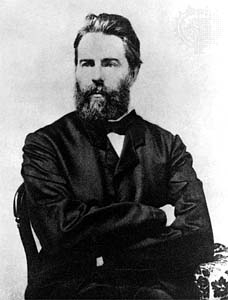

Herman Melville’s short story “The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids,” which appeared in the April 1855 edition is a curious and not well known gem. Its language may seem musty and Victorian (though with flights of brilliance), its core theme of social criticism may seem trite and predictable, but woven through this work are the strands of great ideas which are hammered into more successful works in other short stories and novels (“Bartleby” and the Confidence Man would be notable examples). But this short story is noteworthy because not only does it appear in Harper’s, it marks a reaction to the works of an earlier Harper’s writer. Melville was a Harper’s reader from the magazine’s launch, and a regular subscriber from 1852. Melville’s notes and correspondence show that the magazine played a vital role in his intellectual life, and moreover, that what he read in its pages provided substantial stimulus for his creative output.

One work in particular captivated Melville at this time, and it was Charles Dickens’s Bleak House, which appeared in monthly installments over a period of almost two years, 1852-53. I discussed Harper’s relationship with Dickens and the process of publishing Bleak House here.

Recall that Bleak House, arguably the greatest work of the greatest Victorian novelist, is a tale of the law and the legal profession, and that Dickens sets the scene very elaborately at the work’s beginning. He starts with a dense settling fog which has laid hold of the embankment, of the Temple and the Inns of Court, indeed of the heart of the Lord Chancellor, the figure who sits at the very center of it all. The imagery and language that Dickens employs is powerful, engrossing, and it is perhaps the most successful opening of any of the Dickens novels. Melville, as is plain from several references, was quite taken by the power of this metaphorical opening in which the urban geography of London’s legal sub-city has taken on aspects of the human spirit, at once aspiring and enchained. In the “Paradise of Bachelors” Melville works to copy it, laying a long and careful geography of lawland “in the stony heart of stunning London.” His description is meticulous in detail, and it moves backwards and forwards in time, coming to a focus on the Temple, the Knights Templar. “A moral blight tainted at last this sacred brotherhood,” he reminds us, a hint of the moralizing to come. And then the conversion of this relic following its conquest by the legal profession. And now, we learn, the name has a different connotation:

To be a Templar, in the one true sense, you must needs be a lawyer, or a student at the law, and be ceremoniously enrolled as member of the order, yet as many such, though Templars, do not reside within the Temple’s precincts, though they may have their offices there, just so, on the other hand, there are many residents of the hoary old domiciles who are not admitted Templars.

The Temple is, Melville tells us, a paradise, or as much a proximation as man can fashion. Dr. Johnson, Charles Lamb among its non-lawyer denizens.

(Compare this by the way to the opening pages of “Bartleby,” which seems to transplant the lawyers’ stony heartland from the precincts surrounding Chancery Lane to those abutting Wall Street.)

But this very elaborate scene setting comes in the end to something jovial and simple. Melville has a dinner invitation to dine at the Temple with nine young bachelor lawyers, some perhaps still in their pupilage and thus burdened with the obligation of dining, for the dinners at the inns of court served the double function of providing a basis for training and education. So the cartography of Fleet Street, Holborn and Chancery Lane turns quickly to that of the elaborate dinner which marks the legal feast time. Oxtail soup gives way to turbot, roast beef is followed by saddle of mutton and game fowl, and then the essential puddings; and the amazing array of beverages: clarets, sherries and the mandatory port wine. The luxury and grandeur of the dining process are as impressive as the absence of greens, fruits and vegetables.

But it is not merely the opulence of the environment that catches Melville’s attention but also the convivial nature of his hosts. They have a rare sort of fellowship; they truly care about one another. “It was the very perfection of quiet absorption of good living, good drinking, good feeling, and good talk. We were a band of brothers.”

A glimpse of paradise among a world of lawyers? Think what an odd appearance this is in a literary tradition where lawyers usually appear as subhuman, self-absorbed, power-crazed monsters. And consider the cold hearted world of lawyers crafted by the master in Bleak House. Alas, Melville is fully capable of depicting this darkside, as we see in “Bartleby,” where a more threatening, existentialist aspect appears. But here the author is attempting to paint a different world. He is showing us the world of privilege, the young sons of the aristocracy, of the landed gentry, of the rising middle class. They face no material needs. They live in a world of lavish creature comforts, and indeed it is no stretch to describe the feast that Melville records as an act of gluttony. Do they consider, in their discussions of art, music and professional advancement, even briefly the conditions of the world beyond their stone fortress of affluence?

Melville is, alas, too fine a guest to intrude so coarsely upon their merriment. But that such questions crowd his mind becomes apparent in the following paragraphs, as he leaves the glamorous world of London’s city and arrives in a harsh paper mill in New England. As his title tells us, he moves from paradise to hell (Tartarus, ????????, the “place below”). Again the process of mise-en-scène is carefully attended to, and the language is far more Gothic than the description of the Inner Temple (though that, with its reference to knights in armor was Gothic enough), the situation is dark, bleak and oppressive. The words “Dantean gateway” and “Devil’s dungeon” appear in the same paragraph. He lays the scene at Black Notch on the Blood River near Woedolor Mountain, but this is fictional. (From his writings, however, we can zero in on the factory which served as the model for his horrific portrait. It was Carson’s Mill on the banks of the Housatonic River in Dalton, Massachusetts, part of an operation that subsequently came to be Crane & Co.) Here he comes to a paper-mill which employs a group of young women to do its tedious, and often quite dangerous work. Melville finds the conditions dehumanized and appalling.

Nothing was heard but the low, steady, overruling hum of the iron animals. The human voice was banished from the spot. Machinery—that vaunted slave of humanity—here stood mentally served by human beings, who served mutely and cringingly as the slave served the sultan. The girls did not so much seem accessory wheels to the general machinery as mere cogs to the wheels.

He walks us through the mill. Through the collection and processing of rags. “Among these heaps of rags there may be some old shirts, gathered from the dormitories of the Paradise of Bachelors” he writes, drawing the first connection between heaven and hell. The narrator passes to a room in which the rags are shredded with giant mechanical blades.

”Those scythes look very sharp,” again turning toward the boy.

”Yes, they have to keep them so. Look!” That moment two of the girls, dropping their rags, plied each a whet-stone up and down the sword blade. My unaccustomed blood curdled at the sharp shriek of the tormented steel.

Their own executioners; themselves whetting the very swords that slay them, meditated I.

As the tour of the mill comes to its end, Melville pauses for some curious philosophical reflection. He thinks of the product, the paper, the blank page. He thinks of the challenge, the pain and uncertainty, faced by the writer staring at that blank page. He thinks of the humanity entrapped in the machine to produce it. It is a truly existential moment.

Then, recurring back to them as they here lay all blank, I could not but bethink me of that celebrated comparison of John Locke, who, in demonstration of his theory that man had no innate ideas, compared the human mind at birth to a sheet of blank paper; something destined to be scribbled on, but what sort of characters no soul might tell.

This passage might just as easily have figured in “Bartleby,” which is thematically very close to this shorter tale. It is no wonder that for his most existentialist work, Melville took a copyist, a scrivener, a man who developed an inexplicable fear for filling the page with copy. In “Bartleby” we see a parallel to “Paradise,” for a well-educated man is reduced to the role of a machine (indeed, the role of copyist went into decline with the arrival of carbon paper and disappeared altogether with the arrival of photomechanical reproduction), simply churning out copy as the maids of Dalton tended the machines to make paper. The inspired aspect of writing, the creative process, has disappeared. But even given the opportunity, Bartleby faces pure angst at the prospect.

But aside from the dehumanizing concept of placing humans in the service of machines, Melville is appalled by the sexism of what he observes. He contrasts nine bachelors with nine “maids;” he points to the opportunities that young men have and young women do not. In particular he points to the oppression visited upon unmarried women.

For our factory here, we will not have married women; they are apt to be off-and-on too much. We want none but steady workers: twelve hours to the day, day after day, through the three hundred and sixty-five days, excepting Sundays, Thanksgiving and Fastdays. That’s our rule. And so, having no married women, what females we have are rightly enough called girls.”

”Then these are all maids,” said I, while some pained homage to their pale virginity made me involuntarily bow.

”All maids.”

Again the strange emotion filled me.

The parallels here to the writings of Franz Kafka are very powerful. Kafka, of course, was an insurance company lawyer and he passed his days at the office dealing with what an American would call “workmen’s compensation” cases. He recorded in graphic detail the violent scenes in which factory workers lost digits and limbs to industrial machinery. His job was to carefully assess and limit his employer’s payoff on the claims. And the inhumanity of this entire process troubled him tremendously. This imagery runs throughout his work, from the three novels and into the short stories. “Paradise” approaches many of his clinical descriptions and Ein Hungerkünstler presents imagery which is strikingly like “Bartleby” and his act of self-assertion in the form of “I should prefer not to, Sir.” So we see each of these signatures of Kafka’s modernity are already present in Melville’s work, which indeed forms a conceptual bridge from the sentimentality and romanticism of Dickens to the existentialist critique of Kafka.

“Paradise” is surely one of the minor Melville short stories, but it still conveys a powerful message and it is extremely useful when seen as a building block. We are watching an artist grappling with the work of the greatest master of his day, harvesting useful themes and devices and transposing them to a new and perhaps higher plane. This work is transitional, a center point in an on-going process, helping us understand Melville’s mind and his creativity. But we should not forget the centrality of Harper’s Magazine to this whole process–introducing Dickens to the American market and in providing a forum to those like Melville who appreciated his work and found an element of artistic inspiration in it.