Ursula K. Le Guin, “Staying Awake. Notes on the Alleged Decline of Reading.” Harper’s, Feb. 2008.

In her recent biography of Condoleezza Rice, Elisabeth Bumiller tells us that Condi, a former professor and provost at Stanford University, has a curious relationship to books — curious at least for an academic. As she was growing up, Rice relates, her parents piled books up on her nightstand and the result was a distaste for reading. “She stopped reading for pleasure, and does not to this day,” Bumiller writes.

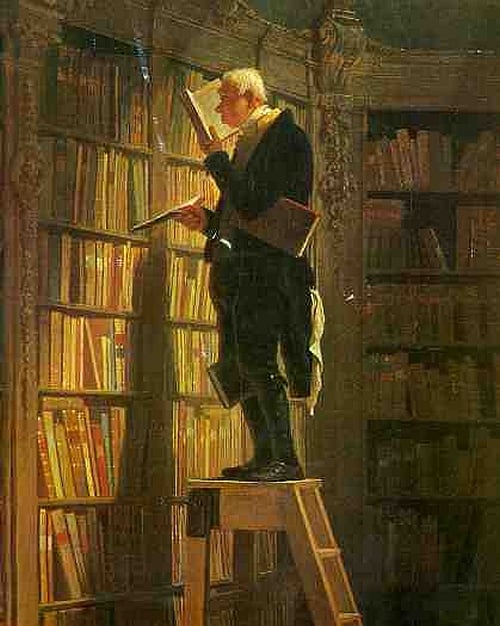

This was the strangest fact of many curious nuggets that can be gleaned from Bumiller’s work. And it left me wondering about modernity’s relationship with books. Many of the most impressive characters I know from history are book fanatics. I think of Seneca and Montaigne, both of whom developed a decided preference for books over people, seeing in them not a retreat from the world as much as a means of opening the doors to new worlds and a better class of interlocutors. As time passes, I develop more sympathy for their approach.

But the rise of mass literacy and a popular print media clearly constitute one of the markers for the modern age. In fact, for the Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant it was the decisive fact which marked a break with the past and the prospect of the development of a human potential that had long been locked away. “Das lesende Publikum,” “the reading public” was this decisive new audience. And “publicity” – mass education through reading – was in his mind the critical path to the development of a new society. This unfolded in the nineteenth century into a middle class for which voracious reading was seen as a tool for social advancement – the so-called Bildungsbürgertum of Germany, the rise and transformation of universities, the birth of countless newspapers, magazines and publishing houses.

So where do we stand two hundred years after this dawn? Ursula Le Guin charts the territory in an article entitled “Staying Awake” in the current issue of Harper’s.

Some people lament the disappearance of the spotted owl from our forests; others sport bumper stickers boasting that they eat fried spotted owls. It appears that books, too, are a threatened species, and reactions to the news are similarly various. In 2004 a National Endowment for the Arts survey revealed that 43 percent of Americans polled hadn’t read a book all year, and last November, in its report “To Read or Not to Read,” the NEA lamented the decline of reading, warning that non-readers do less well in the job market and are less useful citizens in general. This moved Motoko Rich of the New York Times to write a Sunday feature in which she inquired of various bookish people why anyone should read at all. The Associated Press ran their own poll and announced last August that 27 percent of their respondents had spent the year bookless, a better figure than the NEA’s, but the tone of the AP piece was remarkable for its complacency. Quoting a project manager for a telecommunications company in Dallas who said, “I just get sleepy when I read,” the AP correspondent, Alan Fram, commented, “a habit with which millions of Americans can doubtless identify.”

So Condoleezza Rice, it seems, is in good company. But Condi has it just right when she says that she does not read for pleasure:

For most of human history, most people could not read at all. Literacy was not only a demarcator between the powerful and the powerless; it was power itself. Pleasure was not an issue. The ability to maintain and understand commercial records, the ability to communicate across distance and in code, the ability to keep the word of God to yourself and transmit it only at your own will and in your own time—these are formidable means of control over others and aggrandizement of self. Every literate society began with literacy as a constitutive prerogative of the (male) ruling class.

It’s a simple fact that in many respects, educational standards have fallen in the Western world. What was expected of high school students around the turn of the century is daunting.

I see a high point of reading in the United States from around 1850 to about 1950—call it the century of the book—the high point from which the doomsayers see us declining. As the public school came to be considered fundamental to democracy, and as libraries went public and flourished, reading was assumed to be something we shared in common. Teaching from first grade up centered on “English,” not only because immigrants wanted their children fluent in it but because literature—fiction, scientific works, history, poetry—was a major form of social currency.

To look at schoolbooks from 1890 or 1910 can be scary; the level of literacy and general cultural knowledge expected of a ten-year-old is rather awesome. Such texts, and lists of the novels kids were expected to read in high school up to the 1960s, lead one to believe that Americans really wanted and expected their children not only to be able to read but to do it, and not to fall asleep doing it.

Theater goers in New York who have seen the brilliant new performance of Frank Wedekind’s “Spring Awakening” know this was also the case for Middle Europe, where the spirit of adolescents was often brutally crushed under the weight of rote learning in fields of no obvious practical utility.

But the challenge of this century is a different one. It is a pendulum which has perhaps swung too far in the direction of triviality and popular appeasement. The market drives the media, to some extent, and the keepers of high culture seem to fade into the background. And, as Le Guin argues, technology offers up a great diversity of paths to transmitting information and plot lines. Reading requires an active imagination; it takes an effort.

If people make time to read, it’s because it’s part of their jobs, or other media aren’t readily available, or they aren’t much interested in them—or because they enjoy reading. Lamenting over percentage counts induces a moralizing tone: It is bad that we don’t read; we should read more; we must read more. Concentrating on the drowsy fellow in Dallas, perhaps we forget our own people, the hedonists who read because they want to. Were such people ever in the majority?. . .

Television has steadily lowered its standards of what is entertaining until most programs are either brain-numbing or actively nasty. Hollywood remakes remakes and tries to gross out, with an occasional breakthrough that reminds us what a movie can be when undertaken as art. And the Internet offers everything to everybody: but perhaps because of that all-inclusiveness there is curiously little aesthetic satisfaction to be got from Web-surfing. You can look at pictures or listen to music or read a poem or a book on your computer, but these artifacts are made accessible by the Web, not created by it and not intrinsic to it. Perhaps blogging is an effort to bring creativity to networking, and perhaps blogs will develop aesthetic form, but they certainly haven’t done it yet.

What, blogging has developed no aesthetic form?! Le Guin needs to spend more time surfing the internet. But I’m with her on the rest of it. And indeed, the greatest gift of the internet comes in the fact that masses of accumulated learning can be stored on line and made immediately accessible, with tools to understand the details one doesn’t know. It seems to me that Google Books and comparable resources offered up by dozens of academic libraries around the world may be the most important advance that the internet has offered in the last two or three years. For instance, I recently went searching for one of my favorite Meister Eckehart sermons on the web and found among other sources a fourteenth century manuscript fully imaged and accessible from a cloister library in Switzerland. You could almost feel the crackling, buckling parchment on which it was written. It gave me a bit of a workout reading the Gothic fraktur, but being able to absorb an original illuminated manuscript in the comfort of your own study is quite something. What was the great Library of Alexandria compared to this?

Le Guin also offers us the conventional complaint against the publishing industry and its standards.

To me, then, one of the most despicable things about corporate publishers and chain booksellers is their assumption that books are inherently worthless. If a title that was supposed to sell a lot doesn’t “perform” within a few weeks, it gets its covers torn off—it is trashed. The corporate mentality recognizes no success that is not immediate. This week’s blockbuster must eclipse last week’s, as if there weren’t room for more than one book at a time. Hence the crass stupidity of most publishers (and, again, chain booksellers) in handling backlists. . .

To get big quick money, the publisher must risk a multimillion-dollar advance on a hot author who’s supposed to provide this week’s bestseller. These millions—often a dead loss—come out of funds that used to go to pay normal advances to reliable midlist authors and the royalties on older books that kept selling. Many midlist authors have been dropped, many reliably selling books remaindered, in order to feed Moloch. Is that any way to run a business?

Better of course that they should feed Moloch with midlist authors than with children. But the other point lurking here and made quite brilliantly by Arthur Schopenhauer some 150 years ago goes to the industry’s obsession with always shoveling something brand new under our noses, something with a hint of scandal, but the product of an abysmally poor or thoroughly conventional mind. The past offers better writers, better ideas, more helpful friends. But it does not offer the sort of material that can be sold profitably in airport bookshops and in drugstores. Or will it?

Le Guin in any event comes back to this inevitable point: the distinction between true literature and the trivial, and its relevance to the world of commerce.

So why don’t the corporations drop the literary publishing houses, or at least the literary departments of the publishers they bought, with amused contempt, as unprofitable? Why don’t they let them go back to muddling along making just enough, in a good year, to pay binders and editors, modest advances and crummy royalties, while plowing most profits back into taking chances on new writers? Since kids coming up through the schools are seldom taught to read for pleasure and anyhow are distracted by electrons, the relative number of book-readers is unlikely to see any kind of useful increase and may well shrink further. What’s in this dismal scene for you, Mr. Corporate Executive? Why don’t you just get out of it, dump the ungrateful little pikers, and get on with the real business of business, ruling the world?

Is it because you think if you own publishing you can control what’s printed, what’s written, what’s read? Well, lotsa luck, sir. It’s a common delusion of tyrants. Writers and readers, even as they suffer from it, regard it with amused contempt.

Reading, I firmly believe, is a source of relief from tyrants. Both for individuals and societies.