Eine große Rede läßt sich leicht auswendig lernen und noch leichter ein großes Gedicht. Wie schwer würde es nicht halten, eben so viel ohne allen Sinn verbundene Wörter, oder eine Rede in einer fremden Sprache zu memorieren. Also Sinn und Verstand kömmt dem Gedächtnis zu Hülfe. Sinn ist Ordnung und Ordnung ist doch am Ende Übereinstimmung mit unserer Natur. Wenn wir vernünftig sprechen, sprechen wir nur immer unser Wesen und unsere Natur. Um unserm Gedächtnisse etwas einzuverleiben suchen wir daher immer einen Sinn hineinzubringen oder eine andere Art von Ordnung. Daher Genera und Species bei Pflanzen und Tieren, Ähnlichkeiten bis auf den Reim hinaus. Eben dahin gehören auch unsere Hypothesen, wir müssen welche haben, weil wir sonst die Dinge nicht behalten können. Dies ist schon längst gesagt, man kömmt aber von allen Seiten wieder darauf. So suchen wir Sinn in die Körperwelt zu bringen. Die Frage aber ist, ob alles für uns lesbar ist. Gewiß aber läßt sich durch vielen Probieren, und Nachsinnen auch eine Bedeutung in etwas bringen was nicht für uns oder gar nicht lesbar ist. So sieht man im Sand Gesichter, Landschaften usw. die sicherlich nicht die Absichten dieser Lagen sind. Symmetrie gehört auch hieher. Silhouette im Dintenfleck pp. Auch die Stufenleiter in der Reihe der Geschöpfe, alles das ist nicht in den Dingen, sondern in uns. Überhaupt kann man nicht genug bedenken, daß wir nur immer uns beobachten, wenn wir die Natur und zumal unsere Ordnungen beobachten.

A great speech is easy to learn by heart and a great poem is easier still. How hard it would be to memorize as many words linked together senselessly, or a speech in a foreign tongue! Sense and understanding are thus critical to the function of memory. Sense is order and order is in the final analysis conformity with our nature. When we speak reasonably, it is our being and our nature that speaks. When we want to incorporate something into our memory, we always search for a sense or another kind of order as a tool to that end. That is why we utilize the notions of genus and species in the case of plants and animals. The practice of forming hypotheses must be considered in this same light: we are obliged to have them because otherwise we would be unable to retain things. And while this is frequently observed, we must return to it again and again. The question is whether everything is legible to us. Certainly experiment as well as reflection enable us to introduce a significance into what is not legible, either to us or at all: thus we see faces or landscapes in the sand, though they are certainly not there. The introduction of symmetry belongs here too, seeing silhouettes in inkblots, for instance. Likewise the gradation we establish in the order of creatures: truly, all of this is not to be found in the things themselves, but in us. In general we cannot recall too often that when we observe nature, and especially the ordering of nature, it is always ourselves alone we are observing.

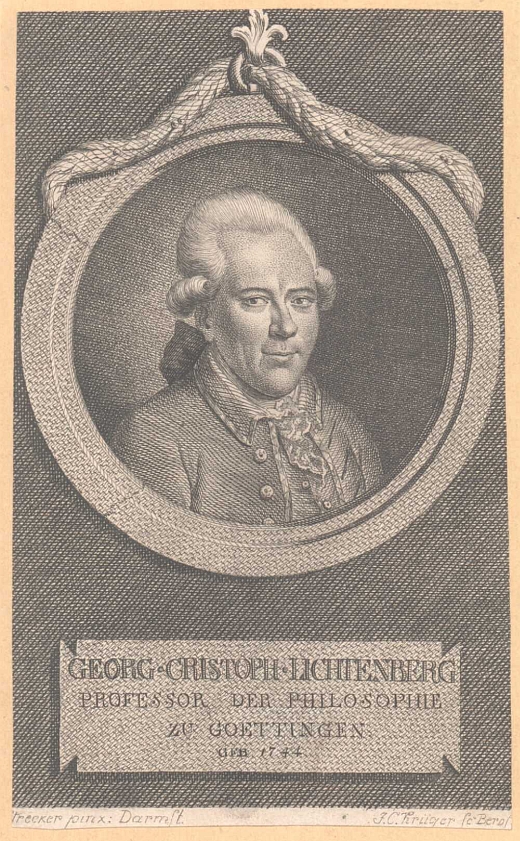

—Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, Sudelbuch ‘J,’ No. 392 (1789) in: Schriften und Briefe, vol. 1, p. 710 (W. Promies ed. 1968)(S.H. transl.)