Die Menschen stehen vorwärts in den Straßen

Und sehen auf die großen Himmelszeichen,

Wo die Kometen mit den Feuernasen

Um die gezackten Türme drohend schleichen.

Und alle Dächer sind voll Sternedeuter,

Die in den Himmel stecken große Röhren.

Und Zaubrer, wachsend aus den Bodenlöchern,

In Dunkel schräg, die einen Stern beschwören.

Krankheit und Mißwachs durch die Tore kriechen

In schwarzen Tüchern. Und die Betten tragen

Das Wälzen und das Jammern vieler Siechen,

und welche rennen mit den Totenschragen.

Selbstmörder gehen nachts in großen Horden,

Die suchen vor sich ihr verlornes Wesen,

Gebückt in Süd und West, und Ost und Norden,

Den Staub zerfegend mit den Armen-Besen.

Sie sind wie Staub, der hält noch eine Weile,

Die Haare fallen schon auf ihren Wegen,

Sie springen, daß sie sterben, nun in Eile,

Und sind mit totem Haupt im Feld gelegen.

Noch manchmal zappelnd. Und der Felder Tiere

Stehn um sie blind, und stoßen mit dem Horne

In ihren Bauch. Sie strecken alle viere

Begraben unter Salbei und dem Dorne.

Das Jahr ist tot und leer von seinen Winden,

Das wie ein Mantel hängt voll Wassertriefen,

Und ewig Wetter, die sich klagend winden

Aus Tiefen wolkig wieder zu den Tiefen.

Die Meere aber stocken. In den Wogen

Die Schiffe hängen modernd und verdrossen,

Zerstreut, und keine Strömung wird gezogen

Und aller Himmel Höfe sind verschlossen.

Die Bäume wechseln nicht die Zeiten

Und bleiben ewig tot in ihrem Ende

Und über die verfallnen Wege spreiten

Sie hölzern ihre langen Finger-Hände.

Wer stirbt, der setzt sich auf, sich zu erheben,

Und eben hat er noch ein Wort gesprochen.

Auf einmal ist er fort. Wo ist sein Leben?

Und seine Augen sind wie Glas zerbrochen.

Schatten sind viele. Trübe und verborgen.

Und Träume, die an stummen Türen schleifen,

Und der erwacht, bedrückt von andern Morgen,

Muß schweren Schlaf von grauen Lidern streifen.

The people stand forward in the streets

They stare at the great signs in the heavens

Where comets with their fiery trails

Creep threateningly about the serrated towers.

And all the roofs are filled with stargazers

Sticking their great tubes into the skies

And magicians springing up from the earthworks

Tilting in the darkness, conjuring the one star.

Sickness and perversion creep through the gates

In black gowns. And the beds bear

The tossing and the moans of much wasting

They run with the buckling of death.

The suicides go in great nocturnal hordes

They search before themselves for their lost essence

Bent over in the South and West and the East and North

They dust using their arms as brooms.

They are like dust, holding out for a while

The hair falling out as they move on their way,

They leap, conscious of death, now in haste,

And are buried head-first in the field.

Yet occasionally they twitch still. The animals of the field

Blindly stand around them, poking with their horn

In the stomach. They lie on all fours

Buried under sage and thorn.

The year is dead and emptied of its winds

That hang like a coat covered with drops of water

And eternal weather, which bemoaning turns

From cloudy depth again to the depths.

But the seas stagnate. The ships hang

Rotting and querulous in the waves,

Scattered, no current draws them

And the courts of all heavens are sealed.

The trees fail in their seasonal change

Locked in their deadly finality

And over the decaying path they spread

Their wooden long-fingered hands.

He who dies undertakes to rise again,

Indeed he just spoke a word.

And suddenly he is gone. Where is his life?

And his eyes are like shattered glass.

Many are shadows. Grim and hidden.

And dreams which slip by mute doors,

And who awaken, depressed by other mornings,

Must wipe heavy sleep from grayed lids.

—Georg Heym, Umbra Vitae, first published in Umbra Vitae (1912)(S.H. transl.)

I have just posted an original translation of Georg Heym’s Umbra Vitae – the “Shadow of Life,” one of the most accomplished of the German Expressionist poems. It paints a dark, mysterious and painful portrait of life. It is filled with great foreboding, a sense of impending doom, a society on the brink of destruction. And perhaps the author’s sense is that this destruction is well-earned. The poem dates from 1912. Shortly after it was composed, Heym died from a freakish accident which had been foreshadowed in a strange dream he had recorded a year and a half earlier.

The composition of the poem is rather conventional, ten stanzas and its rhyming pattern is also conventional. However, the language is astonishing, beautiful, mysterious and then grating. It seems typical of the Expressionism one associates with Gottfried Benn, for instance, in some respects; indeed, like Benn it seems to drift in and out of a morgue. It features a preoccupation with death.

But the opening stanza contains some of the most peculiar and haunting phrasing of the period. “Die Leute stehen vorwärts in den Straßen,” he writes, using words that seem at odds with accepted rules of ergometrics and physics. “Stehen” of course suggests standing, stagnation, a cessation of forward movement. But this is combined with words of action, “vorwärts,” for instance. The same dichotomy of action, inaction appears repeatedly in the poem. I rendered this literally as “stand forward,” conveying the dichotomy of action and stagnation. I am open to readers who can think of something better. But note the repetition of an indecisive angularity, an awkwardness of the human existence: “In Dunkel schräg,” “Sie springen, daß sie sterben,” “Sie strecken alle viere/Begraben,” “Wer stirbt, der setzt sich auf, sich zu erheben.” It’s not easy to understand these phrases, in fact at first blush they seem senseless, crazed.

But I see Heym pointing to the contradiction between lives led in social animation—work, school, social interaction—but lacking internal content. It points to an internal cry against a society which is too straight-laced, which suffocates the individual. The arrested, twisted position of individual humans seems to signal this condition, call it a primal Angst.

There is a strong psychological element in this poem. It starts with the voice. What is the perspective of narration? It seems detached, distanced from the scenes observed. It identifies scenes and brings them into sharp focus, but then the focus dissolves once more. And it seems to operate on several levels of reality. In some cases the description is certainly of a very real landscape. In others it is hallucinatory, perhaps the interpretation or recollection of a dream.

The first two stanzas also introduce a very curious element of astronomy. People are obsessed with observing the heavens, with a fiery-tailed comet, he writes. They conjure the one star. In a sense he is describing something well documented. In 1910, Haley’s Comet returned, but unexpectedly a series of further comets were noted, including the great January 1910 comet which caught the northern hemisphere by surprise. Newspapers recorded it as a sensational affair all across the globe. Sales of telescopes were brisk, and people did indeed gather on rooftops and focus their lenses on the heavens to watch the comet’s approach. Noted scientists speculated on whether the earth would be struck by one of these comets, with unpredictable but likely catastrophic results. Here is an interesting collection of stories that appeared in the New York Times in the first half of 1910 concerning the comets.

But Heym’s comets are not the stuff of science. Note how they wind or creep (schleichen) around the towers. Clearly he is using the comet as a metaphor for something else. But what? Is it superstition? An unwarranted faith in science? Is it people filling their lives with meaningless knowledge, the passion of the German Bildungsbürgertum? Each of these is a plausible construction. Moreover, there are two literary references I see built into these two stanzas, neither of which is likely to be apparent to an English-speaking reader. The first is a famous passage from a historical-religious poem by Martin Opitz, the seventeenth century Silesian poet, who wrote of rockets winding around crenelated towers. This occurs in an apochryphal vision of a city being destroyed amidst great human suffering and loss of life, Opitz’s experience from surviving a siege during the Thirty-Years War. Heym’s poetry is separated by three hundred years from Opitz and another Baroque Silesian, Andreas Gryphius, but it has remarkable similarities to their work. And not incidentally, Heym was born and raised as a boy in Silesia before his father moved to Berlin as he reached the age for the Gymnasium. The Baroque architectural detail is a fairly obvious give away, and Heym’s fascination with the work of the Silesian Baroque poets is since well documented.

The second is the notion of stargazing—the term he uses—for purposes of divining the future, which in the German literary tradition surely brings Schiller’s Wallenstein trilogy to the fore. It raises the possibility of divination as a science, but also mocks the likelihood that humans will master it, it suggests their efforts are a folly. This meaning also seems woven into these stanzas.

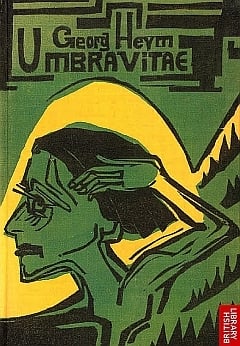

Heym’s work offers us a distinctly urban landscape, though it is a bizarre one, wondrous and perhaps a bit nightmarish. It might be a vision of Salvador Dali’s, or perhaps even better, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s. In any event, Kirchner discovered this poem shortly after Heym’s death and became obsessed with it. He prepared a set of woodcuts to illustrate the entire Umbra Vitae collection, and some very striking cover art. The Kirchner-designed edition of Umbra Vitae is often taken as the Gesamtkunstwerk of the Expressionist period.

After the first two stanzas, the poem takes a rather morbid if not ghoulish turn. We read of suicides “moving in the night in great hordes,” reminding perhaps of a zombie film, of illness and deformity, of animals assailing cadavers. A series of revolting, or at least extremely unpleasant tableaux are rolled passed us. The reader must come quickly to reject this as an account of reality. Rather this is an inner exploration, the thoughts of a tortured soul. There is an intense, pained dissatisfaction with modern urban life, with its well trod paths of education, and business or professional life, of social convention. Is this life called “death”? That is a dichotomy I suppose in the poem. And eyes “like shattered glass” because, perhaps, the doors of reality have been shut, no longer are they able to reflect the wonders of life. This is the sense in which a person can be “dead,” yet prepared to rise again. (There is of course also the spiritual dimension, the allusion to Christian doctrine, not to be dismissed, but also not quite focal to the meaning.)

But the last stanza seems designed as a key to those who may have made the journey through the poem without sensing the artist’s meaning. It is about “dreams,” we learn. It is also about “shadows,” the unfortunate combination of constraints imposed by society which limit the human possibility. But Heym leaves us, at length, on a more positive note. It is awakening, a rebirth, a healing—“wiping the heavy sleep from the eyes.”

Heym appeals and repels at the same time, like a good Expressionist. But his life reflects the thoughts in this poem. His father was a well known military lawyer, and Georg was slated to follow in his father’s footsteps as a lawyer. But he was revolted by the idea. In fact the descriptions he offers in his journal of the work of a lawyer couldn’t be printed in polite space. So I’ll be impolite:

They have put my nature in a straight jacket. I am bursting through all the brain-stitches, and now I am compelled to be fed like an old sow through the snout with f*!@k-s$#&t-swine lawyer’s crap, until I puke. I would rather piss on this swine feed that take it in my muzzle. I feel a great drive to create. I have the health to produce something.

Georg Heym, Dichtungen und Schriften, vol. 3, p. 152 (K. Schneider ed. 1968)(S.H. transl.)

Heym died at the age of 24, and the circumstances of his death are every bit as odd as Georg Trakl’s—his Austrian counterpart. Heym was quite taken with Freud and his concept of the interpretation of dreams and in July 1910, he carefully logged a recurrent dream he was experiencing, the meaning of which left him troubled:

I found myself standing on the banks of a great lake which seemed to be covered with a type of stone coating. It struck me as a sort of frozen water. On occasion it seemed to be like the sort of skin that forms on top of milk. Some people were moving on the lake, people with bags or baskets, perhaps they were going to market. I ventured a couple of steps, and the plates held. I felt that they were very thin, since as I stepped upon them they swayed back and forth. I had gone for some time and then a woman encountered me, who cautioned me to turn back, the plates would soon break. But I persisted. And suddenly I felt that the plates were dissolving beneath me, but I did not fall. I proceeded further, walking upon the water. Then the thought occurred to me that I might fall. In that moment, I sank into green, slimy, kelp-infested waters. Still, I did not feel lost, I began to swim. As though by a miracle, the shore, though first distant, drew closer and closer, and with a few strokes I landed in a sandy, sunny harbor.

Dichtungen und Schriften, vol. 3, p. 185 (S.H. transl.)

On January 16, 1912, Georg Heym and his friend Ernst Balcke decided to go skating on the Havel River outside of Berlin. After many days of hard freezes, the river had frozen entirely over. Skating ahead of him, Balcke saw the ice crack under his feet and he fell into the icy waters below. Heym, horrified at the scene, rushed to help pull him out of the water, but as he approached the hole, the ice gave way beneath him, and he also fell into the water. Workmen on the shore observed the scene but were powerless to help. Heym and Balcke drowned or died from hypothermia and were extricated from the river two days later. Heym’s recurrent nightmare was realized. And the nighmare he saw for his world came just a few years later. Some write poetry, some dream it, others live poetry. Georg Heym did all three.