The great theorist of modern criminology, Cesare Beccaria, dispensed some simple advice. The lawmaker, he argued, should keep his focus on criminalizing those things which cause the gravest offense to society and should resist criminalizing trivial matters. When the reach of criminal law grows too broad, it runs some fatal risks. One is that individuals who hold state power will be much more tempted to wield criminal justice for corrupt political ends. And the other is that the criminal justice system itself will become a subject of ridicule as the populace has increasing difficulty finding the essential element of justice without which it is a fraud.

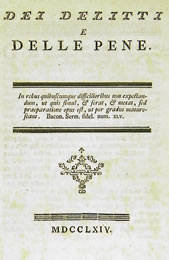

America’s framers drew very heavily on Beccaria and his thinking. I recently saw John Adams’s heavily annotated copy of Dei delitti e delle pene, and Jefferson and Madison both also drew inspiration from the work. The American justice system is of course the offspring of the English system, but the thinking of writers like Beccaria played an important role in crafting the new product.

But today the American Justice Department continues down a strange detour on a road to abuse that Beccaria understood very well. Two examples demonstrate it.

In Birmingham, Alabama, a politically ambitious U.S. attorney named Alice Martin has secured ten indictments of Democratic political figures and their allies. Martin keeps the indictments under seal, so she can release them drop by drop to suit the needs of a political plan, namely the campaign of her Republican compatriots to take control of the state’s legislature. And according to recent reports, Martin has grown so apprehensive that the public will grow wise to her schemes that now she has launched an effort to identify a Republican to charge, too. The offenses charged in these indictments can be summed up in the case she has brought against a 63-year-old retired social studies teacher named Sue Schmitz. The focal charge is that Schmitz had a contract to run a civics program and that she didn’t put in as many hours as she was required to because she was in Montgomery as a state legislator. No doubt it’s Schmitz’s service as a state legislator which provokes the prosecution. You see, Schmitz committed a very serious crime in Martin’s view. She is a Democrat.

So the Birmingham prosecutors have crafted a novel crime. It’s called “school teacher underperforms lesson plan.” And it’s a felony. I wonder how many school teachers have been prosecuted by federal prosecutors for underperforming their lesson plan? My bet is that we’re going to find this is a highly selective category, and all the school teachers selected for prosecution are Democratic legislators. And indeed, why stop with school teachers under a private contract? Why not focus on public office holders, like a U.S. attorney, who only seems to straggle into her office on days when she’s giving a press conference? Perhaps the public inspection of absenteeism should start with those leveling the charges. But all of this falls smack into the center of what Beccaria would call the abuse of law.

The rational approach to a teacher who underperforms would not be to prosecute, but to give her a warning and then fire her for nonperformance. And here it turns out that indeed the contractor did fire Schmitz. She contested that, and the court concluded she was right and that she had been wrongfully dismissed. You can examine the ruling here. Though this ruling is about process, and not the substance of the accusations against Schmitz, it’s another little detail that the newspaper working hand-in-glove with the prosecutors on this little political caper masquerading as “good government” doesn’t want you to know.

The case of the school teacher in Huntsville is one example plucked from dozens of bogus, politically inspired “public integrity” prosecutions that the Bush Justice Department has concocted all around the country. In each of them we see a clear grand design, namely, to influence the elections process for the benefit of the Republican Party. So we see tens of millions of taxpayer dollars and massive resources being devoted to illegitimate and improper ends that in the end produce injustice and undermine public confidence in the Justice Department and its commitment to its principal mission.

And then let’s look at the flip side: the enormous number of serious crimes which go uninvestigated and uncharged because of an official but unannounced Justice Department policy: “We don’t care.” James Risen does a very good job in yesterday’s New York Times of developing an aspect of that. The article is entitled “Limbo for U.S. Women Reporting Iraq Assaults.” He looks into another one of the 38 cases of serious assault or rape involving women who accepted extremely dangerous missions to work as contractors in Iraq in support of the nation’s military mission there. The law gives the U.S. Department of Justice plenary authority to investigate and prosecute crimes in these circumstances. But what is the Justice Department’s attitude? Apparently, it can’t be bothered. It’s far too busy prosecuting 63-year-old school teachers who enter into criminal schemes to be elected to a state legislature while being Democrats. Here are Risen’s opening graphs:

Mary Beth Kineston, an Ohio resident who went to Iraq to drive trucks, thought she had endured the worst when her supply convoy was ambushed in April 2004. After car bombs exploded and insurgents began firing on the road between Baghdad and Balad, she and other military contractors were saved only when Army Black Hawk helicopters arrived.

But not long after the ambush, Ms. Kineston said, she was sexually assaulted by another driver, who remained on the job, at least temporarily, even after she reported the episode to KBR, the military contractor that employed the drivers. Later, she said she was groped by a second KBR worker. After complaining to the company about the threats and harassments endured by female employees in Iraq, she was fired.

“I felt safer on the convoys with the Army than I ever did working for KBR,” said Ms. Kineston, who won a modest arbitration award against KBR. “At least if you got in trouble on a convoy, you could radio the Army and they would come and help you out. But when I complained to KBR, they didn’t do anything. I still have nightmares. They changed my life forever, and they got away with it.”

Ms. Kineston is among a number of American women who have reported that they were sexually assaulted by co-workers while working as contractors in Iraq but now find themselves in legal limbo, unable to seek justice or even significant compensation.

Now back home in Ohio, Ms. Kineston would have gone to her local police station and sworn out a claim for the sexual assault. It would have been investigated and if the evidence supported her claim, the perpetrator would have been prosecuted. But this is not the way things work in the law-free zone that President Bush has carefully crafted in Iraq. An order was issued making Iraqi criminal law inapplicable. Congress enacted legislation giving the Justice Department the power to prosecute crimes that occur involving contractors instead, to insure that there would not be a vacuum. But with a community of 180,000 contractors over a period of five years, how many violent crimes involving contractors has the Department of Justice actually prosecuted? Zero.

Risen’s article is good on the facts, but falls into some traps on the law. In fact, he makes two statements which are either wrong or misleading.

First, he says “the military justice system does not apply to” contractors. Wrong. South Carolina Republican Lindsey Graham introduced an amendment to article 2 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice which was enacted at the end of 2006, and which makes the military justice system (admittedly not every part of it, only a few core rules) applicable to contractors. Graham was motivated to act after hearing dozens of cases like this one, and being first puzzled and then exasperated by the stubborn indifference of the Justice Department. So at least the military can use the court-martial system. However, there are a number of major issues surrounding its use on civilians, and the Department of Defense still has not presented the implementing rules for Graham’s legislation.

Second, Risen says that the closest statute to provide jurisdictional cover would be the Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act, but “its legal reach is under wide debate.” In fact there are several statutes that give the Justice Department the power to act, not just MEJA (others include the War Crimes Act and the USA Patriot Act). And the suggestion that there is “wide debate” is hardly accurate. There isn’t any debate. What we see instead is a number of bureaucrats—especially in the State Department, but also in the Justice Department—misquoting and misinterpreting the MEJA as part of a feeble effort to disguise their own inaction and indifference to prosecutorial action. What Risen calls “debate” would be better denominated “smoke screen.”

The Justice Department has adopted a policy of official indifference. It could care less about crimes that occur involving contractors in Iraq, they just don’t matter. Note, it doesn’t matter the nature of the crime. This applies equally to murders, serious assaults, rapes and other crimes. For some reason a murder or the gang rape of a young woman from Houston is far less interesting than prosecuting a 63-year-old social studies teacher who made the fatal error of standing for the legislature as a Democrat. My suspicion is that the attitude of official indifference is just as corrupt and political in its nature as the political prosecutions. In the case of contractors, the fear seems to be that any prosecution attracts attention to the heavy reliance on no-bid contracts awarded to a handful of companies with strong ties to key figures in the Bush Administration, like Dick Cheney (Halliburton/KBR) and Condoleezza Rice (Bechtel, Blackwater). To protect political figures from embarrassment, a decision has apparently been taken that any criminal conduct, no matter the nature of it, will simply be ignored. The governing principle could be summarized this way: “either you’re with us or you’re against us.” The “us” in this case is read very narrowly and personally, it seems to refer to those at the pinnacle of power. Are we witnessing the privatization of the criminal justice system? In any event, we are witnessing a sweeping and systematic betrayal of a public trust.

The Justice Department’s failing is not just that it abuses its resources for political schemes. It also neglects its core law-enforcement mission with respect to serious crime. Is there any way to correct this short of a sweeping replacement of personnel? That would be up to Michael Mukasey. But so far, he seems too preoccupied with waterboarding to focus on anything else.