It’s Oscar season, and documentary filmmaker Alex Gibney faces a dilemma that his contemporaries could only dream of. He’s competing against himself. Of the six feature-length documentaries up for an Oscar, two reflect his work: “No End in Sight” and “Taxi to the Dark Side.” But Gibney has no equivocations over where his heart lies, namely, with “Taxi to the Dark Side.” No Comment puts six questions to Alex Gibney about the making of “Taxi” and some of the problems he faced along the way.

1. You build the narrative around the life and death of an Afghan taxi driver named Dilawar, who died in a prison at Bagram Air Base, and not on the far better known cases out of Guantánamo or Abu Ghraib. For most filmmakers who have addressed the issue of detainee abuse, the victims remain anonymous and alien. But you succeeded not only in unlocking the details of Dilawar’s death, but turning him into a living breathing human being whose death left a painful sense of loss in his family and community. Explain what led you to Dilawar’s story and why you thought it would provide the central thread necessary to the narrative.

There were a number of reasons why I chose Dilawar’s story. First, he was a pure innocent. Everyone — including his interrogators — believes that he was not guilty of anything except being in the wrong place at the wrong time. So, in Dilawar’s death, we can see the cost of an official policy of cruelty: innocent people are brutalized and, sometimes, killed.

I also thought it would be important, as you say, to show the face of a victim of Dick Cheney’s “dark side” approach. We see where Dilawar lived in Yakubi, a small farming village near the Pakistan border. We discover that this kid — he was only 22 at the time of his arrest — had never spent a night away from his home. We meet his father, beautiful young daughter, and brother — Shahpoor — who says one of the most heart-wrenching things in the film: after Dilawar’s death, he can no longer “taste his food.”

There was also something about Dilawar’s story — as told by Tim Golden in the New York Times — that also haunted me. After the third day of a five-day interrogation, his interrogators had concluded that he was innocent. Yet his guards continued to brutalize him and the sergeant in charge of his interrogation demanded that Dilawar’s interrogators “take him out of his ‘comfort zone.'” That detail in Tim’s piece testified to the inexorable momentum of torture: once you start it’s very hard to stop. Alberto Mora refers to this syndrome later in the film and gives it a name: “force drift,” the observed tendency of interrogators to keep “pushing the envelope” of violence to get results. It’s also something that the psychologist Stanley Milgram noted as part of his experiment in “Obedience.” Subjects would allow themselves to leave the bounds of morality provided they did so incrementally.

The last reason I chose the Dilawar tale was that the echoes from his story reverberated throughout the network of detention and interrogation centers established by the Bush Administration. I used the Dilawar story to show that detainee abuse was not a case of a few “bad apples”; it was the result of a concerted policy. Following the death of Dilawar, the people who interrogated Dilawar (the 519th MI unit) went from Bagram to Abu Ghraib. And the three passengers in Dilawar’s taxi — innocent farmers from the little village of Yakubi — were sent to Guantánamo. There was no real reason to send them there except that, in all likelihood, the Army wanted to make it look like there had been a terrorist conspiracy. (In the film we show that the U.S. military had been fooled by local Afghan militia, who handed over Dilawar to cover up their own rocket attack on a U.S. base.) Dilawar’s passengers spent fifteen months in Gitmo, until they were released. Also, Moazzam Begg — one of the detainees at Bagram who witnessed some of the violence meted out on Dilawar — was also sent on to Guantánamo from Bagram. So following the tale of Dilawar was an organic — and very human — way of looking at the larger story of a policy of cruelty in detention and interrogation.

2. Your film maintains a steady level of tension in its use of prison guards and interrogators to carry the story. Most of the individuals you show were court-martialed, and you give information on the outcome of their trials at the end. But in the documentary itself, these witnesses come across as human figures, indeed, even as sympathetic. This treatment seems to suggest that these young men and women may be guilty of some horrible deeds, but that they’re also victims—that they were let down by a military that failed to give them the training, the experience and the oversight that was their due. So they may have done wrong, but you are not labeling them as the true culprits. Am I interpreting this correctly? Was this ambivalence in the presentation of the soldiers intentional from the outset?

You are interpreting the film correctly. The guards and interrogators are not “pure victims,” as you suggest. Some of them did terrible things. But those who were convicted of crimes were scapegoats because they were punished while their superior officers — who ordered them to commit crimes or, at the very least, condoned them — were not convicted of any wrongdoing. Also, I think they were victims in a way that few people think about. As someone noted in a recent blog of yours, “You don’t torture people and then lead a normal life afterwards.” Even the young men who weren’t convicted of anything – like Damien Corsetti – are haunted by torture that they witnessed.

3. Some of the most compelling footage of the film comes in the closing credits in which you include scenes from an interview you conducted with your father, who was a Navy interrogator, and who was obviously distressed about the changes in military tradition that the Bush administration introduced. Can you tell us about your discussions with your father and how they influenced the film?

My father – Frank Gibney — was a big influence on my life. A longtime journalist and old “Asia hand,” he had learned Japanese during the war so that he could interrogate Japanese prisoners — something he did on Okinawa, one of the bloodiest battles of the Pacific campaign in World War II.

At the time, there had been many reports of Japanese torturing Americans. Further, there was a pervasive view that the Japanese were a new kind of enemy, one that was so fanatical that some of its soldiers (kamikaze) would use airplanes to fly suicide missions. (Sound familiar?) But my father and his fellow interrogators were not taught “coercive interrogation techniques.” They didn’t waterboard anyone as a matter of policy. Just the opposite, they practiced rapport building techniques that were extremely effective in eliciting information despite the supposed “fanatical nature” of the prisoners.

Most important, my father felt that, by not engaging in retribution, he was adhering to a higher standard. “We never forgot,” he says in the film, “that behind the facade of wartime hatreds, there was a central rule of law which people abided by. It was something we believed in. It was what made America different.”

As a former Navy interrogator, he was furious about the Abu Ghraib scandal. As more details emerged about the way that torture appeared to be part of a wide-ranging policy, he was even more enraged. He encouraged me to take on this project. While I was working on “Taxi,” I visited him in Santa Barbara just before he died. One day, he said: “Go get your video camera; I have something I want to say.” We had to turn off the oxygen machine so he would be audible. A foreign policy conservative, he raged against Rumsfeld, Cheney and Bush for upending the very values that he had defended as a soldier. His anger, and his belief that we could — and did — do better offered a ray of hope in a bleak film.

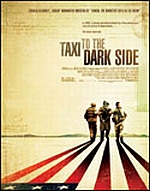

4. As you were getting close to the theatrical release, I understand that “Taxi to the Dark Side” ran into some trouble with the Motion Picture Association of America. Specifically, the MPAA rejected the poster prepared for the film because it showed a hooded figure. Your art, as I understand it, was based on an actual photograph from Iraq, not some artistic recreation. What was the MPAA rationale for its decision? Did you succeed in your efforts to get them to reconsider?

The MPAA — in an email to ThinkFilm, “Taxi’s” distributor — objected to the use of the image of a hooded and shackled detainee in the poster. Comparing it to similar images in horror film posters, the MPAA said it had to be consistent in its prohibition.

There’s an interesting sidebar about the history of the image. As Anne Thompson noted in Variety, the “Taxi” ad art is actually an amalgam of two pictures. The first, taken by Corbis photographer Shaun Schwarz, and actually used in the film, features the hooded prisoner and one soldier. Another military figure was added on the left. Ironically, the original Schwarz photo was censored by the military, which erased his camera’s memory. The photographer eventually retrieved the image from his hard drive.

So this photo is the image that would not die. In any case, we protested that the image, while clearly offensive, should be judged differently because it was a documentary image. The MPAA relented. We have the poster we wanted.

Both the backstory and the MPAA incident were reminders of a prevalent view during the age of Bush: it’s OK to employ torture, just not to show it.

5. It’s now four years after the Abu Ghraib disclosures. The Bush Administration first took the posture that this was all a bunch of “rotten apples.” Of course, your film eviscerates those claims. But now as we enter into an election campaign, some of the Republican candidates have adopted a pro-torture mantra, and it seems that the issue may figure prominently in a national presidential election. Do you think “Taxi to the Dark Side” can inform the public in an election setting?

I hope so. I know that both the campaigns of Clinton and Obama have asked for a copy of the film. But I’ve been disappointed that none of the front runners has stepped forward and said: “I will close Guantánamo on Day One.” And where is the rage over what Mukasey is doing?

Romney has said he wants two Guantánamos. Giuliani — now out of the race — said “waterboarding” is OK so long as the “right” people do it. McCain was heroic in spearheading passage of the Detainee Treatment Act and then, as mentioned in “Taxi,” protected his hard right flank by voting for the Military Comissions Act.

Obama mentioned torture in a recent stump speech and so did Hilary.

But none of the candidates have really presented the issue for what it is. Maybe because they are concerned that up to 35% of Americans still think torture is OK under some circumstances. So there is still a political benefit to slyly suggesting that torture (without ever using that word) is OK. That’s why Bush and Cheney have run on the revenge model: take the gloves off. And that’s an approach, in a time of fear, that plays well to some crowds.

But I can tell you that the letters I have received — from people all across the political spectrum — tell me that viewers are enraged when they see the film. They want to know what can be done to steer our country away from “the dark side.”

“Taxi” also contributes to the political debate in three other ways. First, it eviscerates the “ticking time bomb” excuse for torture. Second, it shows that “detainee abuse” is like a virulent virus – spreading, mutating, building resistance to attempts to stop it – that infects everything in its path. It haunts the psyche of the soldier who administers it; it corrupts the officials who look the other way; it discredits the information obtained from it; it weakens the evidence in a search for justice, and it strengthens a despotic strain that takes hold in men and women — like David Addington and John Yoo — who run hot with a peculiar patriotic fever: believing that, because they are “pure of heart,” they are entitled to be above the law.

Third, “Taxi” makes clear that the war on terror does not need to be waged outside the law. Indeed, it shows that kind of “gloves off” warfare is not effective.

Jack Cloonan (a former member of the FBI’s counter-terrorism task force who appears in “Taxi”) tells me that he is in touch with captured al Qaeda operatives who assure him that our policy of “coercive interrogation techniques” has inflamed a thirst for revenge and continues to serve as a recruiting tool for terrorists.

The goal of most every terrorist (and the stated goal of Osama bin Laden) is to provoke liberal democratic societies to undermine their own principles. Well, in the words of George Bush, “mission accomplished.”

6. In 2005, you got an Oscar nomination for your documentary on the collapse of Enron, “The Smartest Guys in the Room.” This year, you’re up again for “Taxi” and of course you also had a hand in another nominee, “No End in Sight.” How do you handicap the Oscar process? “Taxi” is a documentary with a strong political message. But Hollywood is at least ambiguous on the torture issue, considering the proliferation of torture scenes since 9/11 and the fact that one of its most successful products, Fox’s “24” occupies a diametrically opposed political position on the issue. Are you taking on the Hollywood establishment in the competition for this Oscar? How do you handicap the race?

I have a few jolting clips from “24” in “Taxi.” (As noted in a recent Wall Street Journal piece, next season Jack Bauer goes before the Congress to defend his actions.)

As Fox will tell you, the Hollywood establishment is pretty liberal, as seen by the other nominated films — “Sicko,” “No End in Sight” (which I executive produced), “Operation Homecoming” and “War/Dance.”

If “Taxi” has an edge it is that it seems to appeal to conservatives and liberals; military personnel and civilians.

As far as handicapping goes, who knows? It’s a mystery to me. Last time (with “Enron: the Smartest Guys in the Room”), I lost to a bunch of f***ing penguins!