Douglas Martin, “William F. Buckley Jr., 82, Dies; Sesquipedalian Spark of Right,” the New York Times, February 28, 2008:

William F. Buckley Jr., who marshaled polysyllabic exuberance, famously arched eyebrows and a refined, perspicacious mind to elevate conservatism to the center of American political discourse, died Wednesday at his home in Stamford, Conn. He was 82.

In 1955, Mr. Buckley started National Review as a voice for “the disciples of truth, who defend the organic moral order,” with a $100,000 gift from his father and $290,000 from outside donors. The first issue, which came out in November, claimed the publication “stands athwart history yelling Stop.”

At age 50, Mr. Buckley crossed the Atlantic Ocean in his sailboat and became a novelist. Eleven of his novels are spy tales starring Blackford Oakes, who fights for the American way and beds the Queen of England in the first book.

Larry L. King, “God, man, and William F. Buckley,” March 1967:

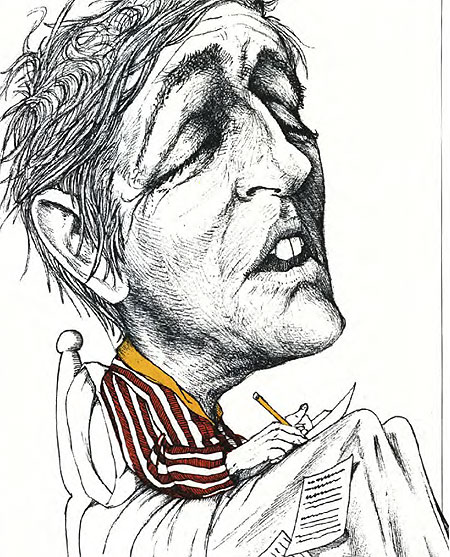

We sized each other up like two fighters in mid-ring, Buckley hooking me with a couple of jokes and scoring with an anecdotal right-cross: “When I sent Norman Mailer a copy of my latest book I turned over to the index in the back and wrote ‘Hi!’ by his name. Knowing Mailer, he’ll immediately go to the index to evaluate his own role, and that ‘Hi !’ will just kill him!” We sipped our coffee and laughed at Norman Mailer. Buckley chuckled at a couple of my stories, didn’t counterpunch when I jabbed him lightly with a couple of my Leftist wisdoms, and was such an eager host that he plopped two ersatz sweet pills into my coffee over protests that I never use sugar. He used all his equipment: the deep, rolling voice; flourishing, theatrical gestures with the cigar; the leaping eyebrows, popping eyes, and the smile that bursts suddenly to display a great sea of teeth.

He was winning on points easily. Then James Wechsler’s ghost warned me not to get amiable.…Well, had he seen poverty at first hand: visited a ghetto, known the indescribable odors of a flophouse, seen the desolate camps of migratory workers, or shanty towns abandoned when the coal vein played out? Buckley stared at me for long moments. “No,” he said, “I have not. That’s one of my shortcomings.” He paused. “I really mean that. It is a shortcoming. I’m not the type to have been of any use to Associated Press, say, if I’d been in Dealy Plaza on November 22, 1963. I learn by reading. After all, you must remember that the people who write the best books on the Civil War were not at Gettysburg.” Another pause, then: “So while it’s true I haven’t actually been around poverty, I think Mr. Harrington has little or no reason for judging me ignorant of the subject.” He seemed nettled and, I thought, for the first time a bit unsure of his ground.

William F. Buckley, “Giving Yale to Connecticut,” November 1977:

The purpose of a Yale education can hardly be to turn out a race of idiots. But one would have thought that was what Yale precisely engages in. Walking out of the Huntington Hotel in Pasadena during the hottest days of the controversy, I espied the Reverend Henry Sloane Coffin walking in. I introduced myself. He greeted me stiffly, and then said, as he resumed his way into the hotel, “Why do you want to turn Yale education over to a bunch of boobs?” Since he had been chairman of the educational policies committee of the Yale Corporation, it struck me that if indeed the alumni were boobs, he bore a considerable procreative responsibility. Certainly his contempt for Yale’s demonstrated failure was far greater than my alarm at its potential failure.

William F. Buckley, “Christians, why do you still believe in God, in the promise of the Cross?” April 1975:

All that from the mind of man. It occurs to me, as I ponder the work of Hewlett and Packard, that what strikes me as extraordinary is child’s play for Hewlett and Packard, who have answers to scientific problems I shall never know enough to frame. Raising the inevitable question: what is it that strikes Hewlett and Packard as extraordinary? David Hume is famous for, among other things, remarking, in the manner (if not the tone) of Oscar Wilde, that he would sooner believe that human testimony had erred than that the laws of nature had been suspended. It occurs to me on reflection that the operative word,

even allowing for the meiotic tradition of the English, is sooner. There is a choice. Mine is that the order of the universe, the arching of the human spirit, the enduring mysteries of love and the unique serenity of faith, ate the result of Central Planning, which took seven

days, not seven seconds, to make a world exciting enough to doubt Him. That is the flirtatious side of God, to reach for a terrestrial metaphor. We should laugh at its presumption, as, after trying it out several times, I can laugh at the black nihilistic teases of Hewlett and Packard. I am programmed to love God and to seek, however vainly, to obey him, and to trust that the course he laid out for me in the grandest voyage, through

time and space, and uncertainty, to infinity and transfiguration, and resolution, is as certainly charted as the toyland course that will lead me from Miami to the Rock of Gibraltar. I shall follow the star of Bethlehem, waywardly; and if I fail to reach it, save that I ever doubted it was there.