While the mainstream media continue with their obsessive-compulsive tantrums about what various ministers distantly associated with campaigns say, and about the misstatements of assorted campaign surrogates, the really important news goes—as usual—essentially uncovered.

A good example of this goes to the War in Iraq. Now the fifth anniversary of the invasion of Iraq would have been an excellent opportunity for a number of the papers and broadcasters to have looked back at their reporting from five years ago with a critical eye. It’s impossible to examine their performance and not conclude that they miserably failed their audience by converting themselves into a megaphone for the Bush administration. There was a wholesale failure of critical analysis, and the results have been tragic. Even among those who supported and continue to support the war, there is a consensus view that the first two years of occupation suffered from a series of catastrophic management failures that should have been reported and discussed in the media, and were not.

I would in fact had even been satisfied if they skipped over the history lesson and went straight to the situation today. But alas, they can’t manage anything like competent reporting out of Iraq today either. What we see is all in terms of analysis of the success of the surge, which is positive news, but in the end not terribly significant. The bigger picture– the strategic aspects of Iraq policy, goes unexamined.

Aside from the short-term tactical successes, how are things going in terms of the longer-term strategic effort. What are the objectives, and how has the effort to attain them progressed over five years, or even just over the last year?

On that score we’d discover, of course, that the goal posts have changed dramatically over five years. Repeatedly the Bush Administration has abandoned its targets and set new ones, ever lower. The process of reassessment and lowering expectations continued even through this week.

But there has been a still bigger, almost entirely unreported story relating to Iraq.

There has been a firestorm about the war inside the Pentagon. It’s been raging for several months now, but the mainstream media, which can find plenty of space to report on Hollywood starlets and their substance-abuse problems, and any candidate’s garbled lines on the campaign stump, can’t find its way fit to report a single line on this.

Yet the smoke from this firestorm has been everywhere. Why did Admiral James Fallon suddenly resign following the publication of a portrait piece on him in Esquire? The word spread about the media, which covered this, as usually, dismissively as “another personnel flap.” In their reporting, it had something to do with the CENTCOM commander’s opposition to launching a new war against Iran.

When I tested this with my Pentagon sources, I was told “wrong.” It is true, they said, that Fallon was opposed to war in Iran, and his public statements had produced friction, but the real source of tension had to do with Iraq policy, not Iran policy. Apparently it had to do with implementation of the existing plan for a draw down of forces. Fallon and most of the Pentagon brass, they told me, were strongly in support of keeping rigorously to plan. The politicos in the White House wanted to keep the surge force in place. And naturally, General Petraeus out in Baghdad espoused whatever view the White House took.

All of this has gotten next to no press coverage. Of course, press coverage is now driven by the elections. And the media tell us, the Iraq War no longer figures as an “important” issue in the elections. Hence there is little space for reporting about Iraq, unless, of course, a presidential candidate goes there. This morning, however, Julian E. Barnes at the Los Angeles Times finally furnishes some solid reporting on this subject.

But inside the Pentagon, turmoil over the war has increased. Top levels of the military leadership remain divided over war strategy and the pace of troop cuts. Tension has risen along with concern over the strain of unending cycles of deployments. In one camp are the ground commanders, including Gen. David H. Petraeus, who have pushed to keep a large troop presence in Iraq, worried that withdrawing too quickly will allow violence to flare. In the other are the military service chiefs who fear that long tours and high troop levels will drive away mid-level service members, leaving the Army and Marine Corps hollowed out and weakened.

President Bush, in marking the fifth anniversary of the Iraq invasion Wednesday, said he would not approve any U.S. troop withdrawals that could jeopardize security gains already made there. Indeed, top leaders at the Pentagon emphasize that any withdrawals must be done with that in mind, and few are pushing for a complete pullout. Still, there are sharp differences that carry broad implications for the U.S. involvement in Iraq.

In the short run, supporters of Petraeus would like to see about 140,000 troops, including 15 combat brigades, remain in Iraq through the end of the Bush administration. Members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and their advisors favor a faster drawdown. Some are pushing for a reduction to 12 brigades or fewer by January 2009, which would amount to approximately 120,000 troops, depending on the configuration of forces.

The discord deepened with last week’s announcement that Adm. William J. Fallon, who served as the top U.S. commander in the Middle East, would retire. Fallon was seen as a key ally of the Joint Chiefs and at odds with Bush because of his support for a speedier drawdown in Iraq.

The L.A. Times account comes very close to what I heard last week from Pentagon insiders. It differs in its failure to give a more comprehensive explanation of the policy underpinnings of the issues that divide the Joint Chiefs from the White House and its sock-puppet commander in Baghdad.

I heard two points stressed repeatedly.

First, the force is stressed, exhausted, overtaxed, not in a position to continue to sustain deployment at the level shown. Pentagon brass sharply criticize civilian planners in the Bush Administration for designing a force which was not capable of handling a sustained large-scale occupation, like the one now in place in Iraq. “Had it been our intention to maintain this sort of presence for this long, obviously we should have had a significantly larger uniformed force.” That, of course, echoes a criticism that Senator McCain has made for several years.

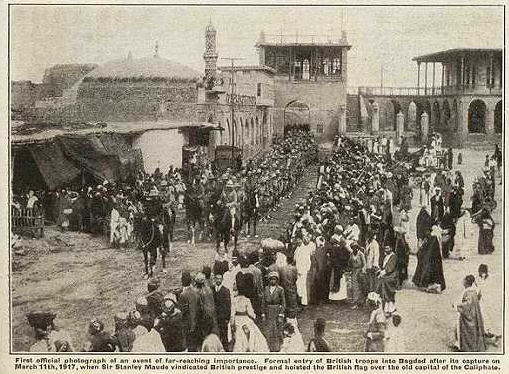

Second, they point to the political dimension. An improved relationship with the dominant political forces in Baghdad is key if political objectives are to be accomplished. Few points unify the Iraqis so thoroughly as the demand that the American drawdown commence in earnest. It is viewed by many senior Iraqi political figures as a test of American intentions. And Bush Administration rhetoric about base-building convinced them that U.S. intentions are no more benevolent than those of British invaders who occupied Iraq from 1918-32, and again from 1941-47. Barnes picked up an echo of this argument, in a defiant question—if the surge is such a success, where are the dividends?

“If the surge has been as successful as it purports to be, this is an ideal time to start the drawdown,” said the officer who has advised the Joint Chiefs. “Violence is at an all-time low. We have turned the corner at the tactical level, so now is the time to redeploy those forces. So people are saying, ‘Why wait four months?’ “

But that, indeed, is the question that the press and the American public should be asking.