Eripuit coelo fulmen, mox sceptra tyrannis.

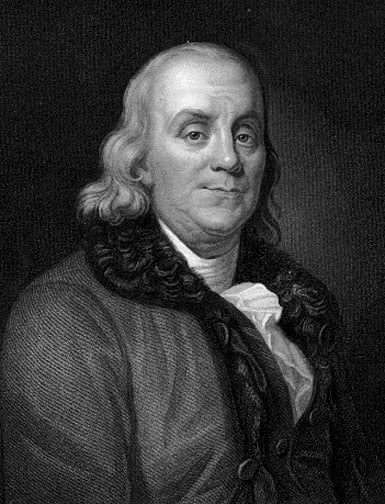

How are we to imagine this man to whom this motto is given – the man “who stole lightening from the heavens and separated the tyrant from his scepter”? As the offspring of a titan, a giant with a hundred arms, a mighty conqueror dripping with human blood? But no, it’s the man whose image I attach who is the worker of these marvels. Mysterious as it may sound, there is a way to disarm him who hurls thunderbolts and his earthly representative – without putting oneself at the head of a half million disciplined and obedient Myrmidons and disposing of an inexhaustible treasure. And indeed when one comes across a man who looks like this Benjamin Franklin, one can be quite confident that he does indeed dispose of such means. . .

As long as humanity requires the power of example, we will have the name of Benjamin Franklin. He ranks high among the small number of men in whom the worth of human nature has achieved its full radiance. If the title “wise” can be bestowed upon a man, then it falls to this human being, who in our own age has had such amazing effect, without ever stooping to diminish another. He devoted his long life to the education of his countrymen, and he put no limitations on his efforts. He learned to dispense with much and still to labor with undiminished zeal. He preached with incorruptible reason of Freedom, Justice, Peace, Brotherly Love, Love and mutual Tolerance. He did so until his dying days, and in his life he showed us examples of each of these virtues.

America is fortunate to have such a wise man spring forward so soon after its founding, a man whose internal harmony was simultaneously at peace with nature, leading him to the discovery of the True in all of its relationships and making him a teacher to all his brothers. The Americans would have secured their independence from the British Parliament without him. However, the moral freedom, the holy respect for Reason in every individual human being, and the internal recognition of the duty to respect the convictions and beliefs of each individual, all of this and so many other inspirations to the practical wisdom of life, and so many other simple, domestic applications which contribute to the comfort and safety of the people, we owe to him. The light which he brought was not relegated to a single corner of the earth; his examination of the inner relationships of nature were able to aid us in our feebleness, particularly as he demonstrated that the energy of the storm which we understood to be trapped in pitch, amber and glass, and which we understood could be conducted in metal, was all of the same creation. But it was characteristic of Franklin’s genius that he quickly demonstrated the practical application of this knowledge, showing us how to protect our own homes from the risk of fire through a strike of lightening. But what is this compared to his contributions to the rights of creatures of reason, for the freedom of the human species, rights which he advanced and justified with irrefutable reason, first to his fellow citizens, and then beyond the ocean. His words form an eternal dam against tyranny and against arbitrary power.

America that gave him life has the closest claims to him, and these he recognizes in their fullest measure. His love of country was his first virtue. The duty of service to his fellow countrymen he placed before his personal sentiments. In 1777, when we met and spoke in Passy, he said: “We are fighting thirty years too soon.” And this conviction rested on his firm distaste for everything that shed human blood. It was a firm aspect of his intellect that reason and virtue alone, even without blood, should have sufficed to secure America’s independence. The concern for extending war caused him to refrain from provocative outbursts against the cabinet in Versailles which his fellow emissary Silas Deane ventured (fortunately, with success) at the time of the signing of the peace treaty. – You unfortunates, upon whose conscience a drop of human blood calls for revenge, how gladly did you purchase with your two Indies the conscience of a wise man, who embraced his fellow creatures with love and remained innocent of the death of a single creature of reason! You, gods of this earth, who do not venture to place your reason in the way of your violent nature, whenever you return to mental clarity, how you must hate yourselves as you look up to this man, who so often refrained from giving free expression to his own opinions. Yet how boundless was the faith and firm devotion to the rights of human equality he expressed! You impoverished rulers of half the world, who so vainly seek to have the other half, how enviable compared with you is this simple American, how eternally greater, richer and happier will he ever be estimated than you. For he knew to dispense with the vanities, his spirit will forever soar above yours.

Impressed by the thoughts of this gentlest and wisest of the inhabitants of our hemisphere, prepared by six years of his instruction which called ever on them to recognize the noblest part of their nature, to value their reason more highly than physical power, patiently to become the master of their passions, his fellow citizens reached the pinnacle of fame which any part of humanity can acquire for itself – they crafted in 1788 a new constitution, which, moreover, cost not a single drop of blood; a sacrifice untainted and worthy to be offered up to the deity, as worthy a sacrifice as any thing of value or terror ever offered up on an altar of yore.

Reason – and only through reason is virtue possible, that is only reason and nothing but reason – that is the magic with which Benjamin Franklin moved earth and the heavens. Reason was used to chain the tyrant who once saw the whole earth as a parade ground for his songs of triumph. Reason is the medium which will allow humanity to achieve its potential. Reason, virtue and freedom – indivisible are these three. Long ago they would have extirpated reason had they been able to compel our subservience through irrationality. But to their distress they require half-reasoning servants, and from even this tiny residue of reason can spring enough sparks to regenerate the whole.

Benjamin Franklin! Noble shadow! Let your teachings move the peoples of the world, let them know your great, unforgettable example. I hear your voice, I hear your words, I will never forget them!:

“You, children of Europe! Honor the divine spark of Reason within you, and perfect it through its use. Freedom can be achieved by virtue alone. Virtue is possible only through reason. Anger and hatred will produce only blood; and with blood alone no man will ever purchase his freedom. No, you will buy yourself shame, regret, torment, you will murder your own happiness and your peace. This is why what man most desires cannot be acquired through blood. Set the spirit of reason free in yourself, and then the freedom of the external world will follow. Carry the consciousness of your own worth in your bosom, keep your jealousies and passions captive and obedient to reason. Children, I tell you, then you will not have believed, hoped, and waited patiently in vain, for God – honor and love Him – God is just! Hold together as is fitting of brothers, love and help one another; be quiet and serious in fortune, take measure in pleasures; be resolute and clear-thinking in misfortune; be industrious, moderate, abstentious, wise: — through this path humanity will achieve its goals; brute force and power will recede, you will be happy, and you will be free!”

—Georg Forster, Erinnerung aus dem Jahre 1790 (1793) in: Werke in vier Bänden, vol. 3, pp. 487-91 (G. Steiner ed. 1973)(S.H. transl.)

This week we mark the 219th anniversary of the death of Benjamin Franklin. I have collected Franklin’s sayings and ephemera for some time. One of the best of them is not well known in America. It records a conversation in Passy in 1777 (Passy was then a commune near Paris, but today it is situated in the sixteenth arrondissement of the city proper). Georg Forster, a German academic, scholar and revolutionary, traveled to France to take the measure of things and sought out Benjamin Franklin for a discussion. Forster spoke perfect fluent English – he had traveled around the world with Captain James Cook and gained renown for his descriptions of life in Tahiti. But aside from his skills as an explorer and natural scientist, Forster was inspired by politics and particularly the American Revolution. He recorded Franklin’s misgivings about the need for war, his concern to bring it to the earliest possible conclusion, and an amazing admonition to the Europeans to seek their freedom, but to avoid spilling blood in the process, words which were particularly prophetic in light of the bloodbath in Paris which was already drawing so close on the horizon. This speech reflects closely the sentiments in Franklin’s A Project for Perpetual Peace, published in France in 1782, which plausibly influenced Immanuel Kant’s work of the same title (1795).

Upon receiving word of Franklin’s death (April 17, 1790), Forster hastened to write up his recollection and to transcribe his remarks. We know that Forster’s conversion with Franklin was in English, but only Forster’s German rendering of Franklin’s words has survived. I have done my best to render them back into English close to Franklin’s idiom, but there are certainly some problematic passages.