How many Mexican presidents did the CIA have on the payroll?

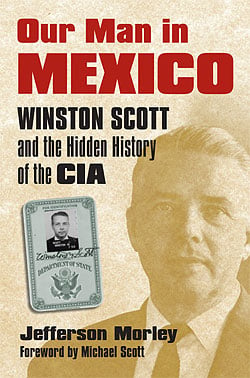

A veteran Washington journalist, Jefferson Morley is the national editorial director of the non-profit Center for Independent Media in Washington, which sponsors a network of statewide online news sites, including WashingtonIndependent.com. He previously worked for 15 years as an editor and staff writer for the Washington Post, and has also published stories in publications such as New York Review of Books, The Nation, The New Republic, Slate, Rolling Stone, and the Los Angeles Times. He recently replied to six questions about his new (and first) book, Our Man in Mexico, a biography of CIA spy Winston Scott. Edward Jay Epstein, in a review of Morley’s book for the Wall Street Journal, wrote: “He uncovers enough new material, and theorizes with such verve, that Our Man in Mexico will go down as one of the more provocative titles in the ever-growing library of Kennedy-assassination studies.”

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

1. How did you come across Winston Scott and what prompted you to write an entire book about his career?

I was working at the Washington Post in 1995 when a lawyer friend, Mark Zaid, introduced me to a client with an interesting story. Michael Scott was a movie director in Los Angeles whose deceased father, Winston Scott, had served in the CIA. As Michael told me his father’s story, I realized that Win Scott, the chief of the CIA’s Mexico City station during the 1960s, embodied a dimension of the Agency’s rise to power from 1945 to 1970 that most historians and journalists have neglected, avoided, or simply not known about. Win Scott wasn’t one of “the very best men” of the CIA, as Evan Thomas called them, the kind of Ivy-League scion portrayed by Matt Damon in the movie, “The Good Shepherd.” He was a different kind of spy. Scott grew up in a converted railroad boxcar in rural Alabama. He came to the Agency not via Yale, but a stint at the FBI. He rose rapidly at CIA headquarters in the 1940s and 1950s. But he did not excel in the salons of Georgetown where a lot of Agency business was conducted. In 1956, Scott asked for a transfer to Mexico City where he rose to covert glory as a virtual proconsul. Along the way, he was deeply involved in some of the biggest intelligence fiascos of the 20th century.

2. Such as?

Kim Philby and Lee Harvey Oswald, to name two. The book documents the previously unknown story of Scott’s friendship in the late 1940s with Philby, a genial British intelligence official who was actually a Soviet spy. Michael Scott showed me his father’s pocket calendars from 1946. “Drinks with Kim,” his father had scrawled. They had dined out together, arranged play dates for their kids, and, at the office, organized covert operations against the Soviet Union. The book also provides the most detailed account yet of how Scott supervised the surveillance of Oswald, as Oswald was making contact with communist diplomatic officials in Mexico City in October 1963, six weeks before he allegedly killed President John F. Kennedy. When Scott died of natural causes in 1971, his longtime friend, James Angleton, the Agency’s legendary counterintelligence chief, went to Mexico City and seized the memoir and a trove of other material from Scott’s home office. (Angleton specialized in such ghoulish work. In October 1964, he had snagged the personal diary of Jack Kennedy’s favorite girlfriend, Mary Meyer, after she was murdered in Georgetown.) Angleton seized the manuscript and tapes because he wanted to make sure that Scott’s account of Oswald’s actions, before and after Kennedy was killed, never came into public view.

3. Oswald’s visit to Mexico City has long been grist for the JFK conspiracy mills. Did you uncover new information about what Oswald was doing there?

I decided early on I could not solve JFK’s assassination but would try to do something more modest and achievable: to describe what the events of 1963 looked like through the eyes of a trusted top CIA official. And they looked very suspicious, which is to say conspiratorial. Scott himself seems to have been duped about Oswald. The book documents how Jim Angleton’s counterintelligence staff cut Scott out of the loop on the latest FBI reports on Oswald six weeks before JFK was killed. This was a deliberate deception that has never been explained. The book reveals that after Kennedy’s assassination, Scott hid a surveillance tape containing Oswald’s voice from Warren Commission investigators. The Oswald tape was probably among the material seized by Angleton. It was destroyed by the CIA in 1986. Win Scott certainly didn’t believe the Warren Commission report. When the Agency in 1967 ordered all hands to pledge allegiance to the finding that Oswald, alone and unaided, killed JFK, Scott responded by ordering a comprehensive review of his Oswald files. Then he retired and wrote his memoir disputing the Warren report and offering his theory that the Soviets were behind Oswald.

4. Was Scott right about that?

He didn’t offer any especially compelling inside evidence to support his theory. Scott knew how vulnerable the Agency was on Oswald. He knew that top officials–including himself, Angleton, and another colleague, an anti-Castro operative named David Atlee Phillips—had far more knowledge about Oswald’s travels and intentions than the American people could imagine. I think Scott wrote his JFK conspiracy theory mainly to protect himself. He concluded that Oswald was not a “lone nut” but rather someone more sinister, an agent who had been used by enemies of America. Scott wrote his memoir because he wanted to say publicly that he was not responsible for the intelligence failure that culminated in Dallas.

5. The CIA’s destruction of the Oswald tape can’t help but bring to mind the recent story of the agency’s destruction of a videotape of the torture of Al Qaeda operative Abu Zubayda…

Both stories reflect the same underlying reality: When a clandestine service is assigned the dirty work of a democratic power to combat a real threat (communism in 1963, Islamist terrorism today), that agency is loathe to disclose its sources and methods to those who seek real accountability. It’s worth noting that Jose Rodriguez, the covert operations chief that destroyed the torture tape, previously served as chief of station in Mexico City. Like Win Scott, he preferred to cover up material evidence in a criminal investigation rather than come clean for history.

6. You report that Scott had three Mexican presidents on the CIA payroll. Does the CIA still maintain significant influence in Mexico?

One of the best Mexico City newspapers, El Universal, ran two front-page stories about “Our Man in Mexico.” There were no denials–not about the CIA’s relationship with top Mexican officials from the U.S. government, nor from Luis Echeverria, one of Scott’s agents who later became president, and who is still alive. To be sure, the Mexican government has changed in fundamental ways in recent years but the military, strategic, and intelligence relationship with the United States has only become deeper and closer than it was in Win Scott’s heyday. The agency’s role in Mexico in the last 20 years–other than Jose Rodriguez’s tenure as station chief–is largely unknown. When it comes to the CIA, the safest conclusion is that the more things change, the more they stay the same.