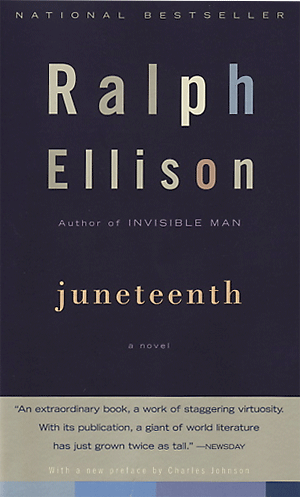

Upon pulling a paperback copy of Ralph Ellison’s Juneteenth off one of my shelves the other day, a friend expressed frustration with its cover. Not its design (a perfectly attractive blue book) but its content. A reader, my friend said, of Ellison’s earlier novel, Invisible Man, who happened in a bookstore upon Juneteenth, would learn that this “NATIONAL BESTSELLER” is by the “Author of INVISIBLE MAN” but not that this work of fiction is, itself, a fiction: that Ellison’s forty-year struggle to finish his second novel had not come to fruition and that Juneteenth was the title given to an unfinished book by a man not its author—a man whose name, tellingly, is kept from its cover.

Of course, inside this copy of Juneteenth, on the title page, Ellison’s literary executor is listed as the book’s editor. What’s more, said executor has not one but two essays in the volume, at beginning and end, that suggest the myriad choices he had to undertake to produce the book in our hands—not least of these the paring down of 2,000 manuscript pages to under 400; the comparison and reconciliation of various incomplete drafts thereof to that end; the breaking of portions of the book into chapters where Ellison gave none; and the naming of the book in keeping with what, as the executor writes, “I think Ellison might have called” the novel.

Naturally, literary history is full of such lucubratory conjecture, instances where stewards of an author’s posterity work late into the nights that follow an author’s extinguished days. The Trial and The Castle are not finished books, however we finish them, and which, in their contemporary editions, offer no warning stickers, either, that their contents are not thrice vetted and twice burnished by their author’s absent hand. Max Brod, as we have come to accept, made many choices of sequence and substance that have been questioned, fruitfully, in subsequent editions of Kafka’s works, just as his first English translators of note, the Muirs, religious people, made him into a writer of religiosity that he was not, sentences remanded by subsequent judges.

Corrections come, dependably, to all literary reputations that warrant them. This is not to say that violence cannot be done to a writer’s work, if briefly, if deeply, by the shortsightedness or dunderheadedness of his fleeting stewards. As such, to my mind, though reading Juneteenth gives rise in one to questions less about what Ellison would have done than what his posthumous editor did do, these are only part of the profitable exercise of literary curiosity that still is a part of the lives of readers today, despite the wanton jackassery that otherwise passes for so much of contemporary cultural conversation.

And yet, with my friend, I would like to think that no harm would come to the reputation of a writer, much less to the potential sales of a publisher, if a cover such as the one above could include, in the interest of both fact and fiction, a single supplemental line: Edited from the Unfinished Manuscript by John F. Callahan.