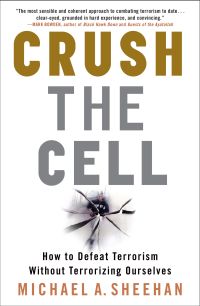

American cable television features an endless parade of “counterterrorism experts,” most of whom have little grounding in their advertised area of expertise. Michael Sheehan, however, is the real thing. A West Point graduate, Sheehan launched his career in counterterrorism as a Green Beret deployed to Panama. He followed up working on the National Security Council in the Bush (41) and Clinton administrations and then became the State Department’s senior counterterrorism adviser, with the rank of ambassador. He then returned to New York City where he served as Deputy Commissioner for Counterterrorism at the NYPD. Random House has just published his book, Crush the Cell, in which he critiques America’s post-9/11 counterterrorism strategies and offers a new tactical approach to dealing with terrorist groups—advising a strong focus on the cell level. I put six questions to Michael Sheehan on the basis of his new book.

1. In Crush the Cell you have some fairly pointed criticism of so-called experts, common enough on cable television, who constantly hype vague threats from Islamist terrorists. You write, “Fearmongering is good business for terrorism consultants,” but you insist that being balanced and accurate in threat assessments is essential. But just assuming that the threat from Al Qaeda has been overstated, what’s the harm in that? Isn’t it beneficial for us always to be on guard against this threat and diligent in following up leads?

The most obvious cost in exaggerating the threat is in the over-expenditure of precious national treasure. This includes billions of dollars of taxpayer money, the deaths of our young soldiers, and the pressure put on our civil liberties in the pursuit of terrorist cells.

In addition to these obvious costs, there is a subtle and perhaps even more pernicious consequence of overstating the threat. It is important to understand that terrorism is an instrument of the weak and that the terrorist depends on a psychological overreaction to an attack on an innocent civilian target. Absent the use of a nuclear weapon, which is highly unlikely, Al Qaeda will have real difficulty affecting our country except through an over-reaction to the next attack. Remember, Hurricane Katrina wiped out a mid-sized American city and shut down commercial shipping in the Gulf of Mexico for several days and our national economy still grew by over 4 percent that year. We are a very resilient nation.

Terrorists succeed when we overreact to their attacks–such as by closing down all our subways, or all our ports, or all our shopping malls if one (or even two or three) were attacked. Those who exaggerate the threat, through ignorance or other motives, amplify the impact of a terrorist attack and could directly contribute to an overreaction by implying that Al Qaeda is everywhere and all-powerful—and that we are weak and vulnerable. Both are false; we are better than we give ourselves credit, and much more resilient.

In New York City, under the leadership of Mayor Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Kelly, we put enormous effort into stopping and responding to terrorism. Yet at the same time, we were committed to re-open our economy as quickly as possible in the event of another terrorist attack—and to not empower the terrorists to cripple our city in fear. Bloomberg and Kelly had balance in their approach; a quiet and relentless determination to prevent terrorism and a determination to avoid panic and over-reaction if they got through.

In London, after the deadly attacks in July of 2005, the British re-opened and rerouted their subway system within three hours of that deadly attack. This sent a powerful message to the terrorists that they will not succeed in intimidating the UK with their attacks.

Does this mean we underestimate Al Qaeda? Never. They must be relentlessly pursued for at least a generation.

2. There now seems to be a strong countercurrent among the experts—arguing that Al Qaeda is not the threat it was built up to be, and pointing to some severe problems that are developing for Al Qaeda, as Peter Bergen and Paul Cruickshank argue in their recent piece in The New Republic. The New York Times highlighted the current debate using Bruce Hoffman and Marc Sageman as models. Hoffman argues that Al Qaeda is alive and kicking, as much a threat as ever. Sageman makes arguments similar to Bergen’s and Cruickshanks, pointing to a “leaderless” organization and saying that the threat focus is bottom-up, namely from the cells. My reading of your book puts you very close to Sageman and Bergen and critical of Hoffman. But tell us how you view this conflict and why it’s important.

In the world of true terrorism experts, the debate is raging—and each of these men are real experts in a world of pseudo experts. Each has taught me a lot about Al Qaeda over the years. And in a sense, they are all correct. Sageman is right in stating that the Al Qaeda movement, especially in the west, is localized in small, disassociated cells and has demonstrated limited operational punch. And Hoffman is right in reminding us that the Al Qaeda central apparatus remains dangerous. Bergen is a true Al Qaeda expert and he and Cruickshank have again contributed important work in highlighting the ideological contradiction in Al Qaeda’s violent doctrines that is undermining their long-term sustainability in the Islamic world.

Although I think there is truth in all of their arguments I lean towards Sageman and Bergen (but I am aware and still respect Hoffman’s deep expertise on the subject). I personally take the long view. I have been involved in counterterrorism since 1979 when I was the commander of a small assault team in a U.S. Army Special Forces hostage rescue unit in Panama. Terrorism is not new, will not go away anytime soon, and there will be more attacks in the future. But it is a threat we can manage if we remain focused and determined.

I think it is important now, almost seven years after 9/11, that our nation takes a more nuanced view of terrorism and particularly our principal nemesis, Al Qaeda. Let’s look at their record. They attacked us strategically three times in 37 months—about once a year—between 1998 and 2001 (the African Embassies in August 1998, the USS Cole in October 2000, and on September 11, 2001). Since then, they have failed to strike us even one time in the United States. They have been limited to a deadly but local campaign in two war zones, Iraq and the Pakistani-Afghan border region. Since 9/11, almost seven years, they have made no attacks in the United States and only two successful attacks in the West (Madrid and London). In other parts of the world, particularly East Asia, they have also been severely degraded over the past few years. You do not have to be an expert to understand that this is a major blow to their operational capability. And it is crucial to understand if they do attack us again tomorrow (which is quite possible and would not change my assessment of them at all), to keep their record of failure in context. It has still been seven years since their last attack, and we should not assume (unless there is overwhelming evidence to the contrary) that they have turned the corner and developed a sustainable attack capability in the west.

And until they can mount a much better operation tempo than one attack every few years, we need not overreact to their capability and turn ourselves inside out through self-paralysis and fear (and hundreds of billions of dollars of waste). As I say in the book repeatedly, we must continue to crush their cells relentlessly for another generation, but not overreact to their occasional attacks in the interim. Of course, if they do sustain terrorist operations (perhaps a few a year), then we will need to mobilize the entire nation, but not now.

The biggest challenge now is to prevent Al Qaeda from exporting its local terrorist capability from Pakistan and Iraq to other parts of the world. So far that is working, and the CIA, FBI, DoD, and DHS all must be commended for their role in containing that threat in those regions. But it remains a major challenge—and one upon which all our counterterrorism agencies must remain focused. More good news is that the link between Iraq and North America is virtually nil; there has been almost no movement of operatives in either direction so far.

3. You’ve been working on the counterterrorism front from the beginning, but after 9/11, it seems an enormous counterterrorism industry was launched, and the news programs were suddenly flooded with a lot of counterterrorism experts who knew next to nothing on the subject of their supposed expertise. To what extent has this turned into an appropriations porkfest? Can you give some good examples? Who should be providing oversight and isn’t?

Since 9/11 the money spent by the U.S. Government borders on the obscene. In my book I talk about driving a rental car through a nondescript Washington military base—and being thoroughly searched, including through my suitcase and dirty laundry. And this was after I showed them my retired military ID. (A terrorist might have planted a bomb in my laundry and my rent-a-car might explode in the underground parking lot of the post exchange!) Across the street, a multi-story hotel—which is a much better terrorist target—has no security at all, because they have to pay, not the taxpayer. Some would say, “but the military has been attacked overseas and targeted in the United States,” and I would say, “yes, and so have multi-story hotels, yet they have not barricaded themselves with mindless security contractors.” This is a small example, but a reflection of a broader mindset.

Since 9/11, the U.S. Government has spent hundreds of billions on activities I consider a complete waste of time and money, or on activities that have a very marginal impact on our safety. Our intelligence budget has almost doubled (from about $25 billion a year to almost $50 billion a year) since the end of the Cold War—when we defeated a true strategic threat that had hundreds of nuclear weapons pointed at our cities and control of all of Eastern Europe.

I am convinced that the degradation of Al Qaeda was done with pre-9/11 resources in the period between 2001 and 2004. It was done with a few thousand agents in the CIA abroad and FBI at home, and a few hundred U.S. Army Special Forces soldiers, Air Force pilots, and CIA operatives in the takedown of the Taliban in Afghanistan. All of these operatives were on the job before 9/11—but were unleashed in its aftermath. Most of the billions spent on new bureaucracies, defense and intelligence contractors, and thousands of new Washington staff officers after 9/11 were unnecessary, in my view. At NYPD, we built a world-class counterterrorism operation within a shrinking over-all budget, and we still reduced crime. We did it the old-fashioned way—by cutting lower priority activities and being very focused with the resources we had. We didn’t build huge new agencies and hire armies of consultants. And although we did get federal monies, the main budget line (the salaries of our investigators) was “taken out of hide” from NYPD’s annual budget.

Both the U.S. Congress and the press have failed in their respective oversight responsibilities. To challenge bloat and pork is not to be weak on terrorism. I don’t consider myself weak on terrorism (I have been accused of being obsessed with Al Qaeda in the 9/11 Commission Report). But few have the guts to get up and say no—that this spending is a waste. And agencies cannot use fear to get their way and cover their butts with unending budget requests.

I would look hardest at the Defense budget and the intelligence budgets first. Although there is plenty of pork in the Department of Homeland Security (millions for new fire trucks for rural constituencies, for instance), the numbers are a small fraction to the billions of dollars the Defense Department and the intelligence community can spend. I consider myself a long-term fiscal conservative, and that includes the sacrosanct defense budget.

4. Dan Pipes, among others, argues that failing to profile shows how we are endangered by our own political correctness. You make the argument that ethnic profiling is a trap and that it will not enhance security. Explain your viewpoint.

Profiling is a hot-button issue, and overblown on both sides of the spectrum. On the one hand, we are all frustrated when “a white haired grandma” is turned upside down by overzealous airport inspectors. But they are trained to treat everyone the same and are subject to random testing by security personnel. It is hard to ask them to have much discretion.

At the same time, it is naïve not to recognize that the vast amount of terrorist damage is done by young males between the age of 17 and 30. A few women have been involved (in Chechnya, Sri Lanka and Palestine), but the hugely overwhelming majority are young men. However, these young men come in all colors and shapes. I always reminded our NYPD counter terrorism detectives about the multi-dimensional threat in the United States. For example, Timothy McVeigh (the perpetrator of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing) was a 26-year-old white guy and an Army veteran. Seung-Hui Cho (the Virginia Tech student who killed over 30 people in classrooms in 2007) was 22 and Asian-American. Lee Boyd Malvo (one of the snipers who paralyzed the DC capitol region in the fall of 2002) was a 17-year-old African-American who was born in Jamaica, and Ramsi Yousef (World Trade Center attack of 1993) was born in Kuwait and of Pakistani origin.

At airports, all are treated the same. However, when it comes to investigations, we look for people plotting to kill us. We do not look to initiate counterterrorism investigations at the senior citizens’ bingo party, but at “hot spots” in the city. This is not profiling, it is common sense—and it is closely monitored to ensure no legal abuse. These investigations are managed in much the same way we conduct criminal investigations against organized crime or drug trafficking. It is not rocket science, but it does require a bit of risk-taking, and some grit and guts. Bloomberg, Kelly, and the NYPD have all of that in abundance.

5. Let’s look at the problem that Olivier Roy calls the “third generation,” namely terrorists who–at a superficial level–are fully assimilated into a Western society. They are citizens with fluent command of language and an understanding of cultural signals; more often than not they are drawn from the middle class or even a prosperous background, and they may even be educated professionals. It’s obviously ridiculous to suggest that this threat can be addressed through social outreach programs targeting the underprivileged. But focus on the law enforcement perspective. How does a police force address this sort of threat; what are the tools that need to be developed? Are we developing them?

The attacks on the Madrid trains of March 2004 that killed over 200 people, and the London subway attacks of July 2005 that killed over 50 people, sent shock waves through the European intelligence and police communities. In Madrid, the attacks were conducted by long-term Spanish residents, primarily of North African origin. In London, the mastermind, Mohammad Sidique Khan (dubbed “MSK”) was born and raised in the United Kingdom and had a job as a teacher’s assistant.

This is extremely problematic for police investigations, because these are people who are part of the social fabric, unlike the 19 hijackers from September 11 who came from abroad to attack. The good news is that although there are many “hotheads,” there are not many intent to procure a weapon for an attack. And also without support from the Al Qaeda central apparatus it has proven difficult for them to make their intent operational. MSK was able to travel freely back and forth to Al Qaeda camps in Pakistan where he received critical training, logistics support, and psychological preparation for his terrorist mission. This demonstrated the continued relevance of “Al Qaeda Central” and the need to crush their capability in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The task of local police and federal investigators is to find these potential cells and to prevent them from linking up with Al Qaeda infrastructure here or abroad. This is done primarily through undercover and informant investigations that are supported by legal wiretaps as necessary (again, just like organized crime). Spending billions of dollars trying to protect our infrastructure is mostly a waste of time and money (with a few exceptions I discuss in the book).

It is easier for a politician or fear-mongering expert to advocate the spending of billions of dollars for these programs (that fund terrorism experts and local pork projects) than to discuss the relatively inexpensive but crucial business of intelligence—which has virtually no constituency in the United States. It can be messy and is not understood by many, and so it is not discussed. We need to have a better, more informed discussion about intelligence operations in our country. Intelligence operations are what protect us from terrorists, and they are relatively inexpensive to do. But it makes people nervous if their police and other law enforcement organizations are conducting investigations in their towns and cities. I understand that concern, and I hope my book contributes to this discussion and moves it forward.

6. In your review of chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear weapons as a near-term threat, you pay special attention to the risk that a “dirty bomb” will be detonated in a major U.S. urban area. Explain why you highlight this risk, what probability you attach to it, and whether you think our local and national law enforcement efforts do enough to take cope with it.

While at the NYPD, I spent a great deal of time analyzing the threat of chemical, biological and radiological (“CBR”) weapons and terrorism (nuclear I left to the Feds). I came to a series of conclusions. First, to build a major CBR weapon is not easy—and second, that Al Qaeda has had no success in that area at all, except perhaps some nascent anthrax capability that was demolished after 9/11 (but even the existence of program is not proven). However, I did find that there are dangerous chemical, biological and radiological substances in the city that could be made into crude bombs. Each of these weapons is problematic, but the radiological bomb, or dirty bomb, seems to be the most dangerous. The combination of available materials, ease of employment and lasting effect of an attack on the bomb site made me worry.

However, we also learned from some of our best national scientists that even a dirty bomb would have a much more local effect than we suspected. A well-constructed terrorist dirty bomb would most likely entail only a few blocks of deadly gamma radiation, and a very limited fallout (a few more blocks) of alpha and beta particles that would adhere to airborne dust particles and be problematic if ingested into the body. This was encouraging, but we continued to do all we could to devise a program to ensure that dangerous materials do not fall into the wrong hands, to detect loose materials on our streets, and respond in the event of an incident. It was a great program and continues to be developed at NYPD.

I still worry about loose radiological materials in New York—and wish our government would do more to tighten up its regulation, which, although improved, in my view is weak (there is too much influence by the “radiological business community” in their own regulation). I do not intend to instill fear with this analysis, just a healthy dose of prudence in protecting these materials from any terrorist organization, Al Qaeda included. Just as with loose nukes, we must do all we can to contain them safely—from Al Qaeda or any other group that might use them.