Late last week, the House Democratic leadership (which is to say, Congressman Steny Hoyer) announced a “breakthrough” in discussions with the White House and the Republicans which would produce a “compromise” in the long fight over the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. I have taken several days to look over the legislation and have some comments.

First, the debate over FISA is of vital significance to our country. The issues are simple. They go to protection of our democracy, now under unrelenting attack by the Bush Administration. Repeatedly, official spokesmen for the administration have mischaracterized the FISA statute, misstated the import of their own proposals, and have used fear as a tool to try to ram through ill-considered legislation that would undermine one of the fundamental principles of the American republic: the notion that the Government’s intrusion into the private dealings of its citizens can occur only after a check through the judicial branch.

The debate raises many other issues. One of the most significant of them is the idea of immunity for telecommunications companies. The evidence at hand now shows that telecommunications companies facilitated criminal surveillance of their customers (i.e., surveillance that violated the limitations of FISA, and was therefore felonious) at the request of the Bush Administration’s rogue Justice Department and National Security Administration. The telecoms have spared no expense lobbying in their effort to get out from under the liability that this presents. Their efforts are plainly paying off.

In a sense, the entire experience with the FISA legislation works to demonstrate the darkest fears that James Madison articulated about war and fear-mongering and their ability to undermine the essential checks-and-balances of the United States Constitution. In 1798, at the height of the Quasi-War with France, which was shamelessly manipulated by the Federalists for partisan purposes, Madison wrote to Jefferson:

The management of foreign relations appears to be the most susceptible of abuse, of all the trusts committed to a Government, because they can be concealed or disclosed, or disclosed in such parts & at such times as will best suit particular views; and because the body of the people are less capable of judging & are more under the influence of prejudices, on that branch of their affairs, than of any other. Perhaps it is a universal truth that the loss of liberty at home is to be charged to provisions agst. danger real or pretended from abroad.

In a like manner, the Bush Administration’s “war on terror” has provided a pretext to transform the American republic into a new form of state. In place of the Founders’ carefully counterposed checks and balances, the Bush Administration offered a new, unfettered executive capable of unilateral action even when encroaching upon the hitherto guarded rights of the citizens. The Bush Administration’s concept was of a National Surveillance State, in which a supposedly benevolent and protecting executive would move towards omniscience through the marvels of new and intrusive technologies.

But the Bush Administration’s secret constitution has another, potentially more worrisome aspect. It presented the president as ultimate interpreter—not guarantor—of the law. As the Stuart monarch who spawned the English Civil War, Charles I, said “rex est lex” (the king and the law are one), so President Bush and his followers enact Richard Nixon’s famous statement, “when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal.”

This principle, that the executive’s views are law, or effectively trump positive law, is poison to America’s constitutional model. So for a Democratic Congress dealing with a Republican president with support dipping to the unheard of depths of 17% in the polls, of course it’s a non-starter, right? Evidently not. Mr. Hoyer and his team really see no problem with the notion of an imperial president. In fact this was the core of their “compromise.” They will give judges discretion to bail the telecoms out of their problems. All the telecoms need to do is demonstrate that the president asked them to do it. Got that? The president’s views trump the law. This “compromise” is insulting and moronic. But that’s not the worst of it. The worst is that it’s a betrayal of the core notions of our democracy.

I agree with the organized bar on the question of telecom immunity: There is no reason for congressional action. If the telecoms acted responsibly and the law is as they claim, they have nothing to worry about. If, on the other hand, they consciously sold out the confidentiality interests of their customers in violation of a criminal statute, then they should pay the price for their betrayal. No aspect of the FISA bill has been more ferociously fought over than this, and it shows us how Washington works in the Rovian age. One constant drives the debate and the action, and that is money. If we survey the horizon of those who have worked intently to bail out the telecoms, we find quickly that each has his campaign coffers lined by his telecom friends. Money talks; Washington is a pit of corruption today, and the corruption knows no partisan limits.

When Hoyer calls this a “significant victory for the Democratic Party,” what exactly does he mean? Perhaps that Democrats now can expect to have the benefice of telecom campaign cash showered upon them. But telecom immunity is not the alpha and omega of this bill. It has other important aspects, which Kevin Drum has summarized:

…the most positive aspect of the bill is that it make clear that FISA and the criminal wiretap laws are the exclusive means by which electronic surveillance may be conducted. It’s true that the old FISA bill says the same thing, and in any case it wouldn’t surprise me if Bush issued a signing statement saying he disagrees with this section, but still, at least it’s something.

However, there are also several negative aspects of the bill aside from telecom immunity, and two of them stand out to me. First, the old FISA allowed NSA to conduct a wiretap for up to 72 hours while waiting for FISA approval. The new bill extends this to a week, allows the surveillance to continue during appeals, and permits the government to use any of the information it collects even if the FISA court eventually rules that the tap is unlawful. This pretty obviously opens the door to some fairly serious abuse in the future.

Second, and more fundamentally, the bill gives wholesale approval for NSA to conduct bulk monitoring of electronic communications (primarily email and phone calls). This is the issue that catapulted FISA into prominence in the first place, and it’s getting surprisingly little attention this time around.

The entire process of data mining is likely to affect the communications of millions of Americans and the exact parameters of the program remain shadowy. This is the soft underbelly of the National Surveillance State, the path by which the state will intrude with little resistance into the lives of the great mass of the citizenry.

Still, it would be foolish to object in blanket to data mining; the national security benefits of efforts in this area are obvious. The concern we have and need to develop is more focused: the Executive’s pursuit of these programs must be subject to the checks-and-balances principles of the Constitution. That means that intrusions cannot be freed from the process of judicial approvals, and that the entire process must remain subject to well-informed, skeptical, and penetrating Congressional oversight. Watching Congress debate these issues inspires no confidence in its discharge of its oversight function. At this point, it is unsurprising that the public is so distraught over Congressional action and that Republicans are largely more fond of the Congress than are Democrats. Congress has a Constitutional duty that focuses on attentive oversight, the preservation of its own prerogatives and of the citizens’ rights against the encroachments of executive power. Congress has miserably failed in this process, and the FISA “compromise” furnishes only more evidence of that failure. More troubling, the Democratic leadership shows us that it has neither a sense of democracy nor of the duty of civic courage in its defense.

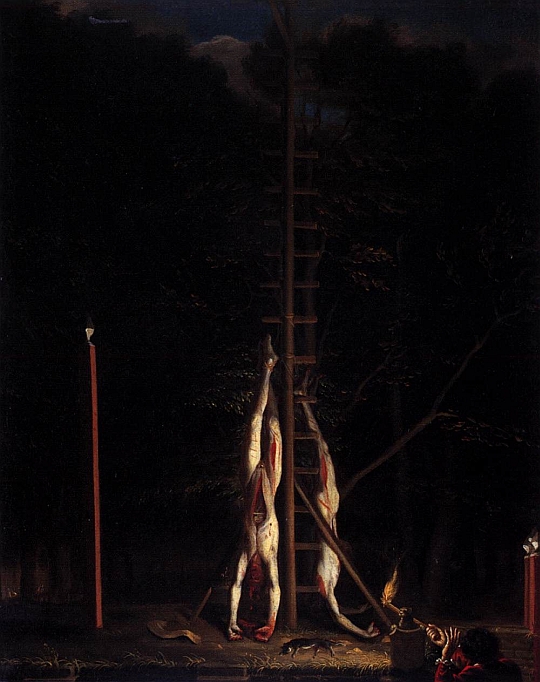

In 1672, Johan de Witt, the valiant defender of the Dutch Republic, was murdered with his brother Cornelius by a lynch mob in The Hague. The Dutch Republic had suffered crushing defeat in war, and the enemies of democracy seized upon the moment to try to bring the republic to an end and to install a monarchy. The philosopher Baruch Spinoza was sent into a bitter depression by these developments; he had come to view the republic and the work of the de Witt brothers as essential to the creation of a prosperous society that promoted free inquiry and science. His own happiness, he found, depended on democracy and the prospect, if never fully realized, of freedom. In his Ethica, Spinoza wrote that democracy, which was so essential to human progress and happiness, was a delicate flower. It grew in a treacherous soil, for the people having won their freedom would quickly incline to take it for granted. Democracy will subsist only when the people value freedom and understand the properties that constitute it. When the people submit to superstition, ignorance, and the lies and distortions that inevitably accompany war, then freedom and its logic are ever at bay. A century later this was the same concern that Madison shared with Jefferson. And today it is the trouble that must occupy the mind of every American sensitive to the legacy and aspirations of his country.

The debate over FISA can quickly descend into a discussion of algorithms and the technology of surveillance; concentration can be lost and eyes glaze over at the cumbersome detail of the statute. But the essence of our freedom and self-understanding as a democracy lies at the core of this highly technical statute. So far, the public is demonstrating a far greater sensitivity to this momentous fact than the professional politicians they have sent to Congress. If these politicians want to survive coming elections, they need to wean themselves of their addiction to telecom campaign cash and instead place their faith in the freedom that our forefathers loved.