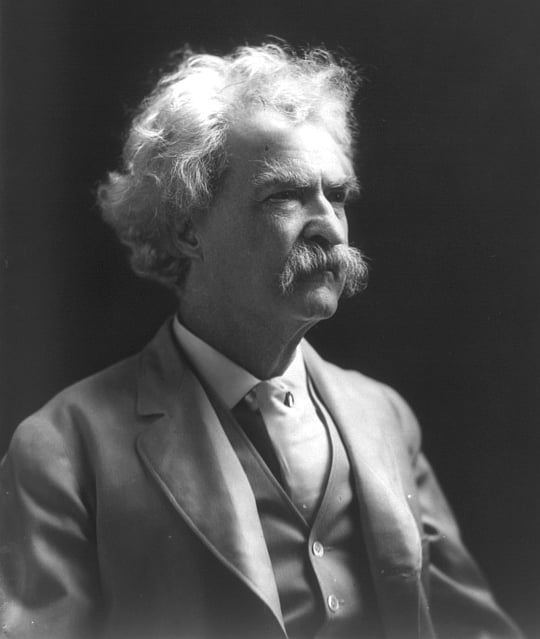

It was March 16, 1901. A lanky man with elegant and flowing white hair and a prominent moustache strode to the podium. He hardly needed an introduction: the audience would immediately have recognized what was arguably the best-known face in America. The event was a meeting of the Male Teachers Association of the City of New York. It was a convivial gathering for dinner at the Albert Hotel in Greenwich Village, at the corner of University Place and Eleventh Street.

The first speaker, Charles H. Skinner, the New York Superintendent of Education, had offered up some words on “Patriotism for the Young,” the need for a better civics curriculum. The need was for children “who are citizens.” “We do not care to own Cuba, Porto-Rico or the Philippines, but we do want to keep them from the dark rule of a barbarian people,” Mr. Skinner offered, reflecting the views so closely associated with President William McKinley. The “barbarian people” were, of course, the Filipinos themselves. Only a few weeks earlier, McKinley had said, of the Philippines: “There was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them.” In fact, Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “The White Man’s Burden,” published in McClure’s little more than a year earlier, bore the subtitle: “The United States and the Philippines.” America had assumed a new mission, as a policeman to the whole world, but as a missionary for Christianity and democracy in its own special corner. The notion of Manifest Destiny stretched at last beyond the Americas, into the lands over which the European powers had contended for the last century or so.

The talk of the day focused on a part of the Philippines where Christianity had not taken root. It was of the Moro insurgency in the southern stretch of the archipelago. The insurrection was dragging on longer than America’s military leaders had envisioned. And the first reports had reached America of the use of highly coercive interrogation techniques, including waterboarding, by American officers. Unlike the situation that the country would face a century later, however, America’s leaders—prominently including Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, who would assume the presidency in only a few months–condemned these practices and insisted on sharp punishment for those involved. Several officers found themselves facing a court-martial in proceedings which would clearly establish waterboarding as a serious crime.

Perhaps when he took the podium Mark Twain had these stories in mind. He put down his cigar.

Yes, patriotism. We cannot all agree. That is most fortunate. If we could all agree life would be too dull. I believe if we did all agree, I would take my departure before my appointed time, that is if I had the courage to do so. I do agree in fact with what Mr. Skinner has said. In fact, more than I usually agree with other people. I believe that there are no private citizens in a republic. Every man is an official. Above all, he is a policeman. He does not need to wear a helmet and brass buttons, but his duty is to look after the enforcement of the laws.

If patriotism had been taught in the schools years ago, the country would not be in the position it is in to-day. Mr. Skinner is better satisfied with the present conditions than I am. I would teach patriotism in the schools, and teach it this way: I would throw out the old maxim, ‘My country, right or wrong,’ etc., and instead I would say, ‘My country when she is right.’ Because patriotism is supporting your country all the time, but your government only when it deserves it.

So I would not take my patriotism from my neighbor or from Congress. I should teach the children in the schools that there are certain ideals, and one of them is that all men are created free and equal. Another that the proper government is that which exists by the consent of the governed. If Mr. Skinner and I had to take care of the public schools, I would raise up a lot of patriots who would get into trouble with his.

I should also teach the rising patriot that if he ever became the Government of the United States and made a promise that he should keep it. I will not go any further into politics as I would get excited, and I don’t like to get excited. I prefer to remain calm. I have been a teacher all my life, and never got a cent for teaching.

Reconstructed from New York City newspaper accounts.