Max Blumenthal reports last week in The Nation on a hushed meeting convened on June 10 in the plush conference room of a Chicago law firm. The presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Barack Obama met with thirty leading figures from the evangelical community. The show was stolen by the Rev. Franklin Graham, the son and successor of the evangelical world’s hottest seller, Billy Graham, better known for his highly inflammatory comments about Islam—which he once called a “very evil and wicked religion.” According to Blumenthal, Graham, who sat next to the candidate,

directly confronted Obama about his supposedly Muslim background and Christian authenticity. . . He peppered Obama with pointed questions, repeatedly demanding to know if the senator believed that “Jesus was the way to God or merely a way.”

It appears that Obama impressed many with his depth in Protestant theology, but in the end failed to satisfy his socially conservative, white southern audience with answers about abortion and gay marriage.

The incident serves to highlight one of the most persistent items of background noise from the Bush Administration’s “War on Terror”: the vilification of Islam and presentation of the American military mission in the Middle East in religious terms as a renewal of the crusades. Bush’s own conduct is totally inconsistent. He has employed incendiary rhetoric, likening the mission to the crusades and regularly attaching the word “Islamic” to the “enemy.” On the other hand he has openly acknowledged the foolishness of this perspective, visited Islamic organizations, and called for respect for people of Muslim faith.

The different perspectives can be explained very simply. One reflects the nation’s strategic interests, which require close cooperation and friendly relations with Islamic states, which have numbered among the nation’s allies since its founding. The other reflects a cynical domestic political calculus, namely the view that the “base”—as Karl Rove calls the Religious Right—can be energized by stirring up anger and resentment against Islam and giving the war on terror a mystical religious dimension. Obama’s Chicago meeting shows exactly how viable these perspectives are in parts of the Evangelical community which stand closest to the Republican Party.

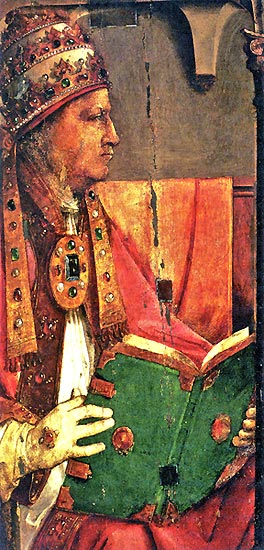

Reading of this encounter made me think of another figure who stands as a strong counterpoint to Franklin Graham and reflects a faith firmly rooted in Christian tradition and ethic–Nicolas of Kues, or Cusanus, the fifteenth-century theologian who made Christian ecumenism and reconciliation of faiths the center of his own writing and speaking. Far from being a quixotic outlier, Cusanus was the bishop of Brixen or Bressanone in German-speaking northern Italy, a cardinal of the Catholic Church and one of the most influential spiritual writers of his day. On the continent, he is widely known and recognized as a key figure of the Renaissance. Ernst Cassierer calls him the philosopher of the Renaissance, for instance. But in the English-speaking world his name and his writings remain largely unknown.

The son of a boat builder in the Moselle River town of Kues, Nicolas was sent to be educated in Deventer, in The Netherlands, and then to Heidelberg and the University of Padua. He quickly established himself as a theologian of brilliance and skill in the mold of Albertus Magnus. But his life took a decisive turn in 1437-38, when he was sent as part of a church delegation to the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. The mission was to explore, with leaders of the Orthodox Church, the basis for a possible reconciliation of the Christian world then split between the Orthodox and Catholic rites. But in his private writings, Cusanus tells us that while in Constantinople, at the crossroads of East and West, he encountered and was fascinated by other faiths as well. First he encountered Armenian and Chaldean Christians and learned of their equally ancient faiths which had established ecumenical liaisons with the Orthodox Church while standing apart from it. But then he discovered the world of Islam and it appears likely that during his stay in the East he had exchanges with Islamic scholars about their faith.

The Orthodox Church was at this time under great stress due to the encroachment of Islamic realms, most immediately the rise of the Turkish empire which had reduced Byzantium to little more than a shadow of its former self. In the West, hopes were high that this pressure could lead to a softening of the Eastern rite’s religious differences and thus to reconciliation in a process that recognized the supremacy of Rome. For most of the Christian world, Islam was synonymous with tales of barbarism and brutality. Christian communities were put to the sword or forced to convert. The Islamic faith was associated deeply with the horrors of war, and its theology was little understood and little studied. But Cusanus was fascinated by it. He secured a Latin translation of the Quran and spent decades studying it. Many Christian leaders in the West spoke of Islam in tones only of hatred and horror. But that was never the case for Cusanus.

On his return trip from Constantinople, Cusanus says he experienced a mystical revelation which subsequently became the focus of his writing and teaching. Cusanus’s writings are philosophical, complex and often not easy to summarize. But here I want to note his relationship with Islam and it requires some context. Cusanus was throughout his life a powerful reconciler. He worked hard to surmount the differences that had erupted between the Pope and the council within the church, and between the Pope and the Emperor. He clamored for reform of the church, identifying specific abuses in a fashion and in tones that are strikingly similar to the Protestant reformers who followed one century later—which has caused some to call Cusanus a “proto-Protestant.” He was also one of the strongest voices within church circles calling for reconciliation with the Orthodox Church. Hence, one of the hallmarks of Cusanus’s thought was an aggressive ecumenism that stressed the importance of shared values over the distinguishing features of custom and rite.

But Cusanus’s drive for reconciliation did not stop with Christianity. He pushed for closer relations with Jews and Muslims as well and worked very hard to identify the religious elements which were common to all the Abrahamic faiths.

His key writing in this regard is De pace fidei (On the Peace Born of Faith) from 1453. It is fairly clear that specific news caused him to pause, put aside other work, and write this book. On May 29, 1453, Constantinople finally fell to the Turks and Byzantium came to an end. The news was greeted with horror and dread throughout the Latin world. Here is what Æneus Sylvius Piccolomini (later Pius II) wrote as the news reached Rome in July:

My hand is shaking and my soul is paralysed by shock. But my disgust doesn’t allow me to be silent and I can’t speak because of pain. Oh, miserable Christianity!… Along with your sorrow, I have to mourn the downfall of Christianity. I mourn the destruction and desecration of the temple of Hagia Sophia, whose fame reaches around the world. I mourn for the many holy churches which were wonderful buildings: now they are subject to destruction and the dirt of Mohammed. Shall I talk about the books which existed in large numbers and which were unknown to the Latin West? Oh, how many names of great men are lost forever? This is Homer’s second death and a second dying for Plato. Where shall we find the spirit of philosophers and poets?… I see faith and culture go down together.

How fear and the threats of war distort perception, then as now. The conqueror of Constantinople, the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, certainly put many Christians to the sword (as they did many Muslims), and forced conversions. But he has become known to posterity as a great patron of the arts and sciences and a man strongly committed to the preservation of the rich legacy of Byzantium, and a man who evidenced more tolerance for Christians and their faith than the Orthodox rulers ever did for his. In 1463, he issued his firman for the protection of Bosnian Catholics, which the United Nations has named one of the oldest and most important documents of official religious tolerance.

Still, leaders throughout Christendom clamored for war, for a new crusade to defeat the Muslims and drive them from Constantinople. Cusanus raised a strong voice against this, arguing the accusations against the Turks were overblown. Where for Piccolomini the Muslims obliterated the culture of classical antiquity, for Cusanus they were a bridge to understanding Aristotle and the preservers of the lost texts. Cusanus questioned the war party; he called instead for reason, restraint and tolerance. And the vehicle for his appeal was an amazing tractate, De pace fidei. It is an extraordinary work, beginning to end.

Here’s the beginning:

News of the atrocities, which have recently been perpetrated by the Turkish king in Constantinople and have now been divulged, has so inflamed a man who once saw that region, with zeal for God, that among many sighs he asked the Creator of All if in His kindness He might moderate the persecution, which raged more than usual on account of the diverse religious rites. Then it occurred that after several days—indeed on account of a lengthy, continuous meditation—a vision was manifested to the zealous man, from which he concluded that it would be possible, through the experience of a few wise men who are well acquainted with all the diverse practices which are observed in religions across the world, to find a unique and propitious concordance, and through this to constitute a perpetual peace in religion upon the appropriate and true course.

The man, is, of course, Cusanus himself. And the vision he presents is extraordinary. Wise men (though “in truth they are not men, but mentalities,” he says) assemble from around the world—Christians, Jews, Muslims, and a Hindu—and plead with God to resolve the differences that divide them. All seek Truth and recognize and accept one God, who must indeed be the same God. Who, they demand to know, has charted the best course? The subtext to their argument is religious harmony and how may it be achieved, but it springs from a realization that religious faith has given rise not simply to war, but to a particularly virulent and inhumane form of warfare. The wise men do not aim to end war, which they recognize is a constant of the human experience, but they do aim to bring an end to religiously motivated warfare. Their conversations search the faiths they represent for their common threads and express skepticism about the importance of the elements of ritual and custom that divide them. Humankind can achieve one true religion with diverse rituals (una religio in rituum diversitate), Cusanus writes.

What Cusanus therefore proposes is tolerance. However, it is not the insulting sort of tolerance, which proposes official indifference. Rather it is a tolerance that has its roots in a philosophical commitment to the search for truth and a recognition that human frailties and imperfections will always lead to mistakes. “For it is a condition of the earthly human estate to mistake for truth that which is merely long-adhered-to custom, indeed, even to mistake this for a part of nature,” Cusanus writes (habet autem hoc humana terrena condicio quod longa consuetudo, quæ in naturam transisse accipitur, pro veritate defenditur.)

But how to reconcile faiths so disparate? For Muslims, polygamy is an accepted practice; for Christians, it is a crime. Christians embrace the notion of a trinity, which Jews and Muslims deride as a vestige of a primitive polytheistic past. For Muslims, paradise is unfolded as a place for carnal pleasures with dark-skinned maidens granted to soldiers who have died in battle, a prospect he says would be unappealing to the sober Christian who aspires to leave behind the life of the flesh. Cusanus gives the answer through the Apostle Paul: man achieves salvation on the basis of faith, not works; these faiths are united in the tradition of Abraham, and their common grounding provides a basis to surmount their differences. The just spirit will achieve eternal life (anima justi hæreditabit vitam æternam). He also adopts an anthropological perspective with regards to customs and rites. They are instituted for important purposes, perhaps, but their ultimate spiritual significance can well be doubted, and their importance can become outlived. Thus a diversity of rites presents no obstacle to the recognition of a common fundamentally shared religion, particularly among the Abrahamic faiths.

Surely, however, the author, a prince of the Roman Catholic church and arguably the greatest theologian it produced in his era, does not distance himself from the sacraments and their importance, and advocates Jesus Christ as a personal intermediator and savior. But with equal clarity, he has answered Rev. Graham’s question to Barack Obama, and the answer he gives is identical to the one that Obama gave Graham (“Jesus is the only way for me. I’m not in a position to judge other people.”)

Cusanus’s vision may be the wild musings of a prelate at the end of an era; they may even be driven by political practicalities—a recognition of the rise of the Ottoman Empire and the short-term futility of efforts to roll it back. But they seem filled with wisdom of immediate relevance to our difficult times. They teach that humanity will always have differing visions of the divine, because the visions will reflect the position and perspective of the human communities that shape them. Cusanus teaches that those who would live their lives with genuine commitment to religious truth must never make religious differences the pretext for war and human suffering. Moreover, the cardinal admonishes us that the very diversity of faith, properly studied and understood, can lead us to better know ourselves and the Divine, and thus lay the foundation for a more lasting peace. This is the meaning of de pace fidei.