I have already intimated to you the danger of Parties in the State… Let me now take a more comprehensive view, and warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the Spirit of Party generally.

This spirit, unfortunately, is inseparable from our nature, having its root in the strongest passions of the human Mind. It exists under different shapes in all Governments, more or less stifled, controlled, or repressed; but, in those of the popular form, it is seen in its greatest rankness, and is truly their worst enemy.

The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of Public Liberty.

Without looking forward to an extremity of this kind (which nevertheless ought not to be entirely out of sight), the common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.

It serves always to distract the Public Councils and enfeeble the Public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which finds a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. Thus the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.

There is an opinion that parties in free countries are useful checks upon the Administration of the Government and serve to keep alive the spirit of Liberty. This within certain limits is probably true; and in Governments of a Monarchical cast, Patriotism may look with indulgence, if not with favor, upon the spirit of party. But in those of the popular character, in Governments purely elective, it is a spirit not to be encouraged. From their natural tendency, it is certain there will always be enough of that spirit for every salutary purpose. And there being constant danger of excess, the effort ought to be by force of public opinion, to mitigate and assuage it. A fire not to be quenched, it demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest, instead of warming, it should consume.

It is important, likewise, that the habits of thinking in a free Country should inspire caution in those entrusted with its administration, to confine themselves within their respective Constitutional spheres, avoiding in the exercise of the Powers of one department to encroach upon another. The spirit of encroachment tends to consolidate the powers of all the departments in one, and thus to create, whatever the form of government, a real despotism. A just estimate of that love of power, and proneness to abuse it, which predominates in the human heart, is sufficient to satisfy us of the truth of this position. The necessity of reciprocal checks in the exercise of political power, by dividing and distributing it into different depositaries, and constituting each the guardian of the public weal against invasions by the others, has been evinced by experiments ancient and modern; some of them in our country and under our own eyes. To preserve them must be as necessary as to institute them. If, in the opinion of the people, the distribution or modification of the Constitutional powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the way which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by usurpation; for though this, in one instance, may be the instrument of good, it is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed. The precedent must always greatly overbalance in permanent evil any partial or transient benefit, which the use can at any time yield.

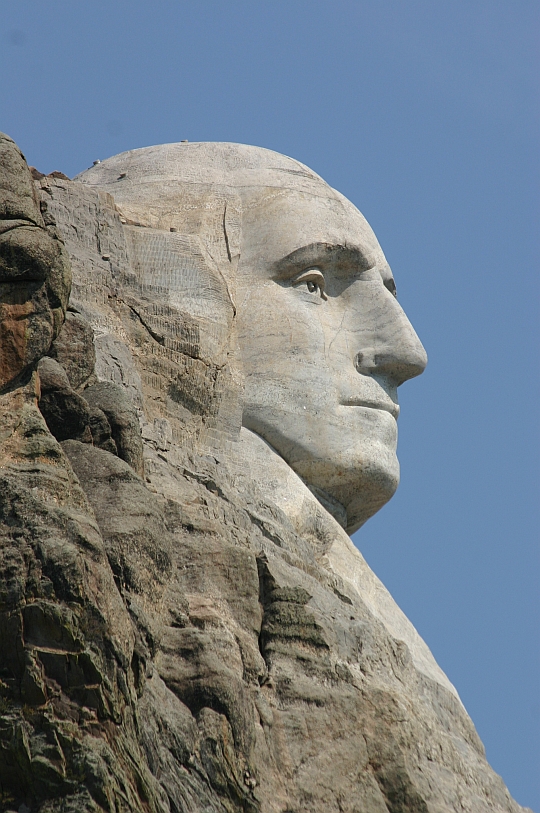

—George Washington, from the Farewell Address, Sept. 19, 1796 in: The Writings of George Washington, pp. 969-71 (Library of America ed. 1997)

George Washington is known for his farewells. There is the remarkable farewell he delivered to the Continental Army on November 2, 1783, and then the farewell to his officers, delivered at Fraunces Tavern in New York City on December 4, 1783–these helped cement his fame as a leader above the nation’s political fray and helped make Washington the inevitable choice after the failed experiment of the Articles of Confederation. But the great farewell is the one delivered as he approached the end of his second term and retired to private life. He takes sum of the challenges he faces and of his accomplishments, but he concludes with some stark words of warning to his fellow citizens.

Two of these warnings have a special resonance for us today. The first is his concern for the threat of “overgrown military establishments, which, under any form of government, are inauspicious to liberty, and which are to be regarded as particularly hostile to Republican Liberty.” Notwithstanding his role as the nation’s foremost military man, Washington consistently showed little enthusiasm for the idea of a standing army and often reflected the perspective taken by Madison, Franklin and others, who saw ample historical precedent for the deterioration of a republic into an authoritarian regime when a leader used threats from abroad as a means of augmenting his authority as a military leader and undermining the authority of the other departments. There is no time in the nation’s history in which this warning has sounded more clearly and powerfully than the present.

And the second warning was against political parties. It is fashionable among historians to say that Washington could not really be speaking about political parties as we know them today. After all, such parties did not really exist. In the mother country there were of course the Tories and the Whigs, which had vied for royal favor and power since the time of the Stuarts. Toynbee tells us that even at the time of the American Revolution these parties were not quite political parties in the modern sense, though they had the germ of the modern mass-membership parties within them.

But I think to the contrary that Washington had a keen eye. The dissonance between Hamilton and Jefferson had torn his cabinet and caused Washington great grief. He clearly foresaw the rise of the Federalist and the Republican (later to be called Democratic) Parties. Indeed, his decision to retire made their rise to the political stage all but certain.

Washington was the first and last American president who could fairly be said to be above partisanship. But he also shows remarkable foresight in identifying the risk that partisanship presents. It is not simply the inflamed sense of rivalry and the temptation to fill positions of public trust with persons of little merit but their political fidelity–these are the obvious shortcomings of every political system. The graver and more fundamental threat is that the republic itself will be collapsed. It is of a “spirit of encroachment” which “tends to consolidate the powers of all the departments in one, and thus to create, whatever the form of government, a real despotism.”

If we take careful measure of the regime of the new George W, the Founder’s unworthy successor, we see Washington’s warning fully realized. The ultimate legacy of the current imperial president is a partisanship with little precedent, a rule by entrenched hacks, but much more disturbingly it is a transformation of the Framer’s Constitution. We will not bid farewell to the current resident at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue soon enough. But will his successor have the resolve and strength to surrender power and help restore our Constitution? That seems an unlikely prospect.

It is simply unrealistic to think that a modern democracy can function without political parties and that a great power like the United States could exist and prosper without a substantial military establishment. The political parties are in a sense democracy’s life’s blood and the military provides the security necessary for democracy to continue. But the Founders were right to point with concern to the threat that each presents to the political system they crafted. Over time, it seems, Americans have forgotten those warnings. But for our democracy to persist, we must keep them in mind, and indeed, the time will shortly be at hand for us to act on them.