On heav’nly ground they stood, and from the shore

They view’d the vast immeasurable Abyss

Outrageous as a Sea, dark, wasteful, wilde,

Up from the bottom turn’d by furious windes

And surging waves, as Mountains to assault

Heav’ns highth, and with the Center mix the Pole.

Silence, ye troubl’d waves, and thou Deep, peace,

Said then th’ Omnific Word, your discord end:

Nor staid, but on the Wings of Cherubim

Uplifted, in Paternal Glorie rode

Farr into Chaos, and the World unborn;

For Chaos heard his voice: him all his Traine

Follow’d in bright procession to behold

Creation, and the wonders of his might.

Then staid the fervid Wheeles, and in his hand

He took the golden Compasses, prepar’d

In Gods Eternal store, to circumscribe

This Universe, and all created things:

One foot he center’d, and the other turn’d

Round through the vast profunditie obscure,

And said, thus farr extend, thus farr thy bounds,

This be thy just Circumference, O World.

—John Milton, Paradise Lost bk vii, lns 210-31 (1667)

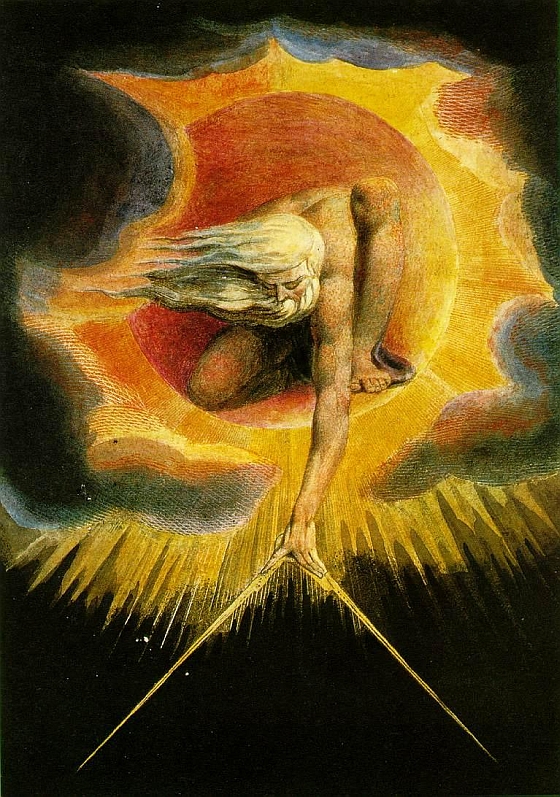

This is one of the most wonderous passages of one of the greatest poems in the English language, the work of John Milton. The William Blake drawing set above it, The Ancient of Days, seems unmistakably influenced by these lines, indeed it recasts the fantastic and tempestuous vision of Milton’s poem and visually realizes his golden compass, a tool by which god measured and cast the earth and continues to wield by way of judgment upon the product. As in much of Milton there is a curious meeting in these lines of the world of Greek antiquity and of the Biblical tradition. But the essence, the conception of a world driven by a celestial mechanics not altogether fathomable by humans, is distinctly a classical Greek idea. This notion was present even in the Homeric vision in which gods regularly appeared equipped with instruments capable of bringing devastation or favor to humankind at their whim, but it lies at the center of the Pythagorean tradition which saw the divine as a cover for a series of mathematical or scientific relationships not now understood, but capable of being learned by the adept. And perhaps the greatest figure in this tradition is Plato, who called god the Divine Geometrician, and who invoked the challenge of Prometheus–the challenge directed to humankind to unlock these secrets.

The golden compass describes a world of order and reason, a place where the possibilities open to humankind are great. But it also describes the limits of this world, beyond which lies maddening and incomprehensible Chaos. This profoundly religious vision which nevertheless accepts science and its central role in man’s happiness is essential to understanding the genius that moved England in the seventeenth century, and which put her on a path toward greatness and leadership in the world. It lies also unmistakably at the center of the American Idea, received from the generation which fought England’s Civil War and whose ideas bore fruit in America’s Revolution.