Noch unverrückt, o schöne Lampe, schmückest du,

An leichten Ketten zierlich aufgehangen hier,

Die Decke des nun fast vergeßnen Lustgemachs.

Auf deiner weißen Marmorschale, deren Rand

Der Efeukranz von goldengrünem Erz umflicht,

Schlingt fröhlich eine Kinderschar den Ringelreihn.

Wie reizend alles! lachend, und ein sanfter Geist

Des Ernstes doch ergossen um die ganze Form —

Ein Kunstgebild der echten Art. Wer achtet sein?

Was aber schön ist, selig scheint es in ihm selbst.

Yet unmoved, you beautiful lamp, gracefully suspended

Here by light chains, you adorn

The ceiling of this almost forgotten folly

About your cup of white marble, whose rim

Is enshrouded with a wreath of ivy golden-green,

A group of children join hands in a circle dance.

How charming is this! Smiling, a gentle spirit

Of gravity descends indeed about the image –

An artwork of the authentic form. Who notices it?

True beauty radiates from a light within.

—Eduard Mörike, Auf eine Lampe (1846) in Sämtliche Werke vol. 1, p. 735 (H. Unger ed. 1974)(S.H. transl.)

I present here an original translation of Eduard Mörike’s short poem “Upon a Lamp,” which occupies much the same position in the German poetic tradition that John Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn” does in the English. Both are prime examples of what the Greeks called ekphrasis (??-??????), namely the practice of one art form imitating another through definition, description and imagery. Among the writers of classical antiquity, ekphrasis had many understandings, but one included the notion that artistic concepts by force of their very universality could be restated, adapted and appreciated anew by subsequent generations, even by other peoples and civilizations; indeed, that the process may be one of gradual perfection of the artistic narrative. But in both cases, the poem can be appreciated on a simple plane, namely as the description of a specific object, or in a more multidimensional framework which includes a measure of irony (the spectator who does not appreciate, or at least not deeply, the artistic virtues of the object) and a assessment of the object within a philosophical system of esthetic judgment. So for Keats, that Grecian urn is contemplated in a manner that later finds its expression in the writings of John Ruskin. But Mörike’s take reflects the esthetic values and perspectives of the German Romanticists and Classicists. It’s common among the scholarship to place Mörike as a late Romanticist, or perhaps as the progenitor of the Neoromanticists–but in fact Mörike draws heavily from the classical school and in many respects his writing reminds one of transitional Classical-Romanticist writers like Friedrich Hölderlin (who crossed paths with Mörike at least once, when Mörike was a student in Tübingen). The imagery taken is decidedly classical and drawn from antiquity. But it is seen through an ironic perspective—the disconcerting clash between the ideal and the reality of the modern day—like many writers of Mörike’s own generation, and that which preceded him. This poem reminds of Hölderlin, Schiller and Winckelmann at least as much as of Schlegel, Wackenroder or Hoffmann. The poem features language of irony and the unexpected at several levels. In the first line, for instance, the word “unverrückt” plays to a secondary meaning—unmoved—of a word more commonly taken to refer to the state of a person’s mental health. From the juxtaposition of these two meanings follows an ironic comment, namely that the viewer anchored in the values of classical antiquity is an odd bird in current society. The lamp which reflects the classical ideal likewise is “suspended by light chains.” In the poem, Mörike gives the chains the sense of being ornamental (“zierlich”), but the word “chains” is of course usually associated with captivity, imprisonment, separation from society. Again the subtle choices of language send a clear message.

This poem achieved its greatest celebrity in the early fifties, when a debate erupted between the great Swiss philologist Emil Staiger and the philosopher Martin Heidegger over its meaning. Both focused on the celebrated last line, probably the best known line from any poem by Mörike. Their difference turned on the word “scheint” which is susceptible to two different interpretations in German. For Staiger the word “scheint” was to be understood in the sense of external appearance (videtur), and hence the poem is a comment on the classical concept vanitas. But for Heidegger, the word had the meaning of the English term which derives from it, namely “shine,” or the Latin that Heidegger mentions, lucet. In this case, of course, the poem takes quite a different sense, namely a reference to an inner beauty following a classical ideal—an ideal that also matches the esthetic perception of writers such as Schiller. In my interpretation, I have adopted Heidegger’s perspective on the poem and its meaning, though I have not been too literal. In fact, I think either view of the poem works. But the Heidegger view is also supported by one of the stranger turns in the last line, where Mörike writes “selig scheint es in ihm selbst.” In normal modern High German, one would have expected the word “sich” where Mörike offers “ihm.” Staiger and Heidegger, both—like Mörike—speakers of the Swabian dialect, say that the use of “ihm” for the reflexive is a Swabianism. But this is strange, because Mörike’s classical-formal poetry, of which this is a prime example, does not use dialect. Another possibility is that this surprise shift is designed to change the perspective entirely, from the object to the viewer (that is, not an artistic object, but a human being). This transformation certainly also follows from the total development of the poem and its remarkable and ironic weave of perspectives.

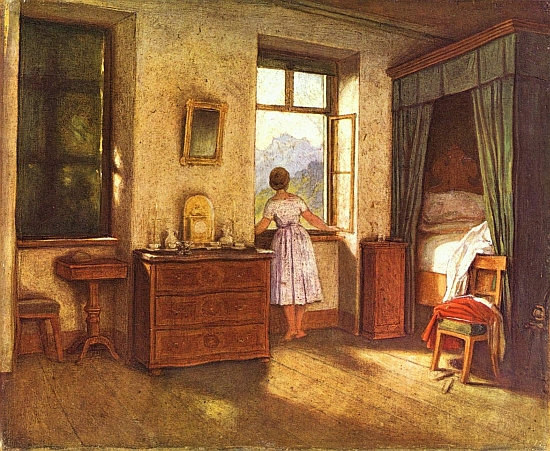

The artwork taken for this poem is also a Romantic study in perspectives in a framework of bourgeois comfort, done by Moritz von Schwind—a very close friend of Mörike’s, especially in his later life.

Listen to Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau sing Eduard Mörike’s “Der Genesene an die Hoffnung” (“He Who Recovers Through Hope”)(1838) in a setting by Hugo Wolf (Mörike-Lieder, 1888).