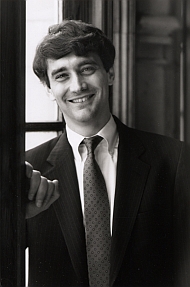

Northwestern University Law Professor Steven Calabresi was a co-founder of the Federalist Society and has been in the vanguard of the conservative movement ever since. He served in the Reagan Administration and the first Bush Administration and has been closely associated with a number of legal theories tied to the Republican Party and its theories of governance. One of them, which has recently come into the public foreground, is the concept of the Unitary Executive. Calabresi has just co-authored a book entitled The Unitary Executive with Christopher Yoo. I put six questions to Steve Calabresi on the concept of the Unitary Executive.

1. Politicians use the phrase “Unitary Executive” as a sort of shorthand for expansive assertions of executive authority. They also tend to imply that this concept is something of fairly recent vintage. Your book makes plain that they’re wrong on both points. Tell us how you define the term, and give us a sense of its historical provenance?

The term “Unitary Executive” dates back to the writings of Alexander Hamilton in The Federalist Papers and to the founding of the Republic. A key question faced by the Framers was whether to have a one-person-executive or an executive-by-committee. In 1787 most of the states had plural executives–governors assisted by committees, called councils. The Framers thought that these committee executives did not work well because they lacked energy and accountability. Alexander Hamilton defended the Constitution’s creation of a unitary executive by saying that it would make the President accountable for everything that happens in the executive branch, and it would give him the power and the incentive to vigorously execute the laws. For this reason, Hamilton and the other Framers vested all of the executive power in the President alone; the constitution creates no council or cabinet with which the President must share the executive power. The cabinet is created by Congress, but the President alone has the power to execute the law.

Congress is always trying to create entities in the executive branch which it can control through its system of maintaining oversight and appropriations committees. These committees are skewed in favor of the interests of the local congressional districts and states of the members who happen to sit on the committees. To believe in the Unitary Executive is to believe that the President should be able–primarily through the removal power–to superintend, control, and direct the actions of his subordinates in the Executive Branch. “Unitary Executive” does not mean the President has inherent foreign policy or other powers to act in contravention of statutes, in my view, although some in the outgoing Administration may have used it that way–this use of the term “Unitary Executive” is entirely confusing and is wrong.

2. You make the argument that all forty-three U.S. presidents have advanced basic ideas associated with the Unitary Executive, although it is clear that some have been far more assertive than others. Although the presidency of Abraham Lincoln may well be a sort of high-water mark of assertions of presidential power, the presidency that followed, that of Andrew Johnson, may have presented the most severe effort to restrain presidential powers in the history of the office. What were the challenges that Johnson faced, and how did they affect the evolving concept of the Unitary Executive?

The need for energy and accountability in the executive was never greater than when Abraham Lincoln faced down the Confederate states during the Civil War. This was a crisis in the execution of the laws because the President was unable to faithfully execute federal law in eleven states that had rebelled against the federal government. Lincoln took some extraordinary steps in response to this crisis–steps that were right only because the crisis was so severe. After Lincoln was assassinated and the Civil War had been won, Andrew Johnson assumed the presidency, and he tried by presidential decree to dictate terms of Reconstruction that Congress and the public in the North opposed. Congress responded by passing a series of statutes over Johnson’s vetoes mandating a more sweeping Reconstruction. Fatefully, President Johnson then failed to execute those statutes. Johnson used his power to fire or remove executive-branch subordinates, to try to put in place loyalists who would assist him in flouting congressional Reconstruction efforts.

Congress should have impeached Johnson and removed him from office for failing faithfully to execute the law. Instead, Congress passed an unconstitutional statute itself–called the Tenure of Office Act–which prevented Johnson from even firing his cabinet members, like the Secretary of War, without senatorial advice and consent. Johnson fired his Secretary of War anyway, the House of Representatives impeached him for doing so, and the Senate failed by one vote in its effort to remove Johnson from office. The belief that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional, which it was, is the only thing that saved this lousy president from being removed by the Senate. All of Johnson’s successors said the Tenure of Office Act had been unconstitutional, and the Supreme Court so held in Myers v. United States in 1926. The episode is widely regarded as confirming that even bad presidents can fire their executive branch subordinates.

3. Unlike Johnson, Franklin D. Roosevelt was certainly one of the most popular American presidents, yet Congress also wrangled sharply with him over presidential appointments—at one point even withholding salaries to force three appointees out. Was it right for Congress to reach to the power of the purse to check the president’s control over appointees?

Roosevelt was a major champion of the Unitary Executive. He took the view that independent agencies and entities were unconstitutional both in arguing a landmark case–Humphrey’s Executor–that he lost in the Supreme Court and in a major legislative initiative that Congress failed to pass. Despite these two setbacks, FDR greatly strengthened presidential powers of control over the Executive Branch by moving the Bureau of the Budget, known today as Office of Management and Budget (OMB), from the Treasury Department to the White House staff.

Congress did at one point cut all funding for the salaries of three members of FDR’s Administration. This kind of action by Congress is permissible, if contrary to the spirit of the Constitution, because Congress has the absolute power of the purse. But while Congress can eliminate an Executive Branch official’s salary, I do not think that it can prevent that official from working for the president for free.

4. The Justice Department has now released a report reflecting an internal probe into the U.S. Attorneys firings of December 7, 2006, which makes some sharp criticisms but also states it was unable to follow matters to their conclusion because figures in Congress and in the White House refused cooperation. Michael Mukasey has appointed a career prosecutor, the Acting U.S. Attorney in Connecticut, to head up a criminal investigation of the matters covered by the report. Congressional Democrats say that Mukasey should have picked someone outside of DOJ for this post. If Mukasey had picked an outsider would this raise “Unitary Executive” concerns?

This whole matter concerns the President’s constitutional power to execute the laws and his duty “to take care that the laws be faithfully executed.” Failure to execute the laws faithfully, impartially, and justly, as occurred during the administrations of Andrew Johnson and Richard Nixon, is and ought to be an impeachable offense. Starting or stopping a criminal investigation for partisan reasons, or removing qualified subordinates because they would not do that, is an abuse of power, a gross dereliction of duty, and a high crime and misdemeanor. In contrast, setting new law enforcement priorities for pursuing vote fraud, or voter suppression, or for cracking down on terrorism or on criminal civil rights violations would all be well within the scope of the President’s “executive power.” Setting new law enforcement priorities does not, however, include trying to help Representative Heather Wilson win re-election, at Senator Pete Domenici’s urging, by changing the usual rules as to the bringing of charges right before an election (if that is what happened here).

As to the investigation of criminal law violations with respect to the U.S. Attorneys firings, I think it bears noting that on January 20, 2009, we will have a new president and administration. Ordinarily, it would be enough to say that it should be the first job of the new administration to investigate this matter, just as it was the first job of the Bush Administration to investigate whether Bill Clinton handed out pardons in exchange for bribes. If there is clear evidence of a violation of long-established law, then prosecutions should be brought. As a general matter though, I think it is desirable that administrations not bring charges lightly against their predecessors since doing so could easily end up criminalizing politics.

My concern in writing the book was with the Ethics in Government Act, which violated the Appointments Clause and was unconstitutional in its limits on the removal power. Neither of those problems are present in respects to Attorney General Mukasey designating a professional special prosecutor chosen from the ranks of the current U.S. Attorneys. I think the tradition of the last 219 years is for presidents to appoint executive branch special prosecutors with a reputation for professionalism when there are serious allegations of high-level, executive branch violation of the criminal laws. There are such allegations here, and it bears repeating that President Bush, former Attorney General Gonzales, and former White House Advisor Karl Rove all deny them. I think Attorney General Mukasey was right that the allegations here require an executive branch special prosecutor, as occurred during Watergate and the Teapot Dome scandal, but I see no reason why he had to pick a Justice Department outsider to do the job. Picking an Acting U.S. Attorney avoids Appointments Clause questions, as well as concerns about assembling an ad hoc posse of lawyers who may want to “get” particular named defendants. Moreover, Patrick Fitzgerald has just demonstrated in the Scooter Libby affair that the Justice Department’s own U.S. Attorneys are independent to a fault. The Acting U.S. Attorney investigating this scandal will be able to weigh the evidence of wrongdoing here with that in other cases she or her office has recently brought using current Justice Department guidelines. This is fair and just to all concerned.

5. The concept of the Unitary Executive is frequently discussed against the backdrop of signing statements, in which the President, while approving legislation, frequently asserts his authority to exercise control over the executive branch. These signing statements have become increasingly controversial–most recently being criticized by a panel of the American Bar Association. Can a signing statement present a sort of secret veto of a piece of legislation that denies the Congress the right to override?

There are three reasons why presidential signing statements might be of legal significance.

First, they are presidential legislative history. Just as House and Senate Committee reports tell us something about the meaning of a new law so too does a signing statement. The President is usually a necessary party to a bill becoming a law so his understanding of the original public meaning of the bill is as relevant as that in a House or Senate committee report.

Second, presidential signing statements are relevant in areas where the executive branch has policy expertise, statutory language admits of multiple interpretations, and the courts have decided to give Chevron deference to executive branch interpretations. In these areas, the president is entitled to let his subordinates know what plausible interpretations he thinks are best as a policy matter.

Third, the President is our Law Enforcement Officer in Chief. It is the president who must take care that the laws be faithfully executed; he cannot fulfill that constitutional duty without giving directions on law execution to his subordinates. Signing statements, like executive orders, provide an occasion for the giving of such guidance.

The president cannot use a signing statement to change the meaning of a law; the challenge comes when the president, in a signing statement or in an executive order, directs the non-enforcement of an Act of Congress that he thinks is unconstitutional, even though the courts have upheld it. The precedent for this was set by Thomas Jefferson who in 1801 directed his U.S. Attorneys to drop all prosecutions under the Alien and Sedition Acts on the grounds that those Acts of Congress violated the First Amendment, even though the courts had upheld their constitutionality. Jefferson’s decree prevailed, and it has ever since been the position of the executive branch that the president ought not to enforce laws that are unmistakably unconstitutional.

6. In a letter to the New York Times responding to Adam Liptak’s recent article on the waning influence of America’s Supreme Court, you wrote

The country that saved Europe from tyranny and destruction in the 20th century and that is now saving it again from the threat of terrorist extremism and Russian tyranny needs no lessons from the socialist constitutional courts of Europe on what liberty consists of.

Of course if you examine the legal writings of Alexander Hamilton, you find it is replete with citations to the authorities of European courts, not of “socialist” but perhaps indeed of “tyrannical” states. Hamilton thought that these decisions reflected the broader experience of mankind and could persuade based on their own arguments and reason. Should America be indifferent to the opinions of other states?

America ought not to be indifferent to the opinions of other nations, and indeed I myself teach a course on Comparative Law to ensure that my students know as much as possible about other countries’ legal systems. My course focuses extensively on Constitutional Law opinions from other countries, which is a subject in which I am very interested. Anyone who is interested in questions of what is good public policy or is intellectually curious ought to study the laws of other countries. Alexander Hamilton did this in the course of arguing in favor of the adoption of the Constitution of the United States. The decision about whether or not the U.S. should adopt our Constitution was a policy question, and it was entirely appropriate for Hamilton to draw on comparative observations in advising voters to support the Constitution. Making good public policy, however, is a different task from interpreting and applying the Constitution we have. Interpretation is not the same thing as policy-making. I think courts ought to interpret the law and not make it. Some of the folks who urge our Supreme Court to look at foreign law elide over this fact in part because they disagree with me that interpretation is not good policy-making. To that extent, we have a good faith disagreement about the nature of the judicial role and the feasibility of the rule of law.

There is also a view, however, that is disturbingly widespread in universities that American society is not as good or as just as is European society. On this point, I emphatically disagree. While Americans have made plenty of horrible mistakes in the last 220 years, we have also invented democracy, written-constitutionalism, bills of rights, and judicial review, and advanced the cause of liberty all around the world. We do not need to catch up with Europe; indeed Europe in some ways needs to catch up with us.