Eh quoi, tout est sensible.

—pythagore.

Homme ! libre penseur—te crois-tu seul pensant

Dans ce monde, où la vie éclate en toute chose?

Des forces que tu tiens ta liberté dispose,

Mais de tous tes conseils l’univers est absent.

Respecte dans la bête un esprit agissant…

Chaque fleur est une âme à la Nature éclose;

Un mystère d’amour dans le métal repose:

Tout est sensible!—Et tout sur ton être est puissant!

Crains dans le mur aveugle un regard qui t’épie:

A la matière même un verbe est attaché…

Ne la fais pas servir à quelque usage impie.

Souvent dans l’être obscur habite un Dieu caché;

Et, comme un œil naissant couvert par ses paupières,

Un pur esprit s’accroît sous l’écorce des pierres.

All things feel.

—pythagoras.

So you alone are blessed, you free-thinking man,

In a world where life sprouts in everything?

You seize the liberty to dispose of the forces you hold,

But in all your plans a sense of the universe is lacking.

Honor in each creature the spirit which moves it:

Each flower is a soul moved by Nature’s face;

In each metal resides some of love’s mystery;

“All things feel!” And all you are is powerful.

Beware, even the blind walls may spy on you:

Even matter is vested with the power of voice…

Do not make it serve an impious purpose.

Often in the most obscure beings resides yet the hidden God;

And like the infant’s eye covered by its lid,

The pure spirit forces its kernel though the husk of stones.

—Gérard de Nerval, Vers dorés (1845) in Œuvres complètes, vol. 1, p. 739 (J. Guillaume & C. Pichois eds. 1989)(S.H. transl.)

Last weekend The New York Times gave us the story of Adam Fulrath, “one of a growing number of single — and yes, heterosexual — men who seem to be coming out of the cat closet and unabashedly embracing their feline side.” The piece is a tribute towards the developmental potential of human interaction with their pets, and it has some real gems, including this: “It’s the unevolved members of the species who tend toward abuse of cats.” A remark worthy of William Wilberforce, and the limitation to “cats” is, of course, unnecessary. The species in reference is, sadly, homo sapiens.

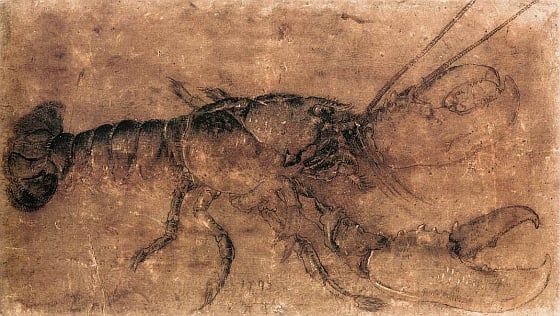

With all due respect for cats, however, let us consider the case for the humble lobster. The poet Gérard de Nerval had a penchant for lobsters, or at least for one lobster. Nerval was seen one day taking his pet lobster for a walk in the gardens of the Palais-Royal in Paris. He conducted his crustacean about at the end of a long blue ribbon. As word of this feat of eccentricity spread, Nerval was challenged to explain himself. “And what,” he said, “could be quite so ridiculous as making a dog, a cat, a gazelle, a lion or any other beast follow one about. I have affection for lobsters. They are tranquil, serious and they know the secrets of the sea.” (The episode is captured by Guillaume Apollinaire in a collection of anecdotes from 1911). Was there any basis to this story? A generation of Nerval scholars attempted to debunk it, but then a letter to his childhood friend Laura LeBeau was discovered. Nerval had just returned from some days at the seaside at the Atlantic coastal town of La Rochelle: “and so, dear Laura, upon my regaining the town square I was accosted by the mayor who demanded that I should make a full and frank apology for stealing from the lobster nets. I will not bore you with the rest of the story, but suffice to say that reparations were made, and little Thibault is now here with me in the city…” Nerval, it seems, had liberated Thibault the lobster from certain death in a pot of boiling water and brought him home to Paris. Thus we know that it was Thibault, and not just “some lobster,” who went for that celebrated promenade in the gardens of the Palais-Royal.

But Nerval’s attitude towards animals is not, as his contemporaries supposed, a casual eccentricity. Rather, he follows in the footsteps of the great Pythagoras, whose thinking has come down to us only in the fragmentary accounts of other writers—including the “Golden Verses” which provide direct inspiration to this remarkable poem. Pythagoras was a vegetarian of a very strict sort; indeed, he would not even harm beans, a fact which according to some accounts led to his death.

“All things feel,” says Nerval’s Pythagoras. There is a ribbon, though it may not be blue, that ties all the forms of life on our planet; their interrelationship is very profound. And humankind is too quick to assume its own mastery and to turn all other things and creatures to its use. But the lobster is a special case, as animal rights activists argue (still much disputed, particularly by the seafood industry) that lobsters are sentient beings with a great capacity for feeling pain which is maximized by the once-favored cooking technique of emersion in boiling water. When Nerval proudly took his lobster for a promenade, he was making the same point he made in this poem: humans make themselves the masters of their environment and the beasts around them, and in so doing have they not lost a sense of the universe and the natural order among beings? Do they not recognize obligations that go with that mastery? It was not, perhaps, quite so comic an act as it may have seemed.

Listen to Camille Saint-Saëns’s piano quintet in A minor, op. 14 from 1855. This isn’t one of his better known works and the critics have never much liked it. They dismiss it as juvenile and imperfect. But that’s wrong, and the last movement, allegro assai, ma tranquillo, is a real gem. It starts with a fugue constructed with a skill that would have brought a smile to Bach. Soon Saint-Saëns introduces a lyrical theme which is entwined in a masterpiece of contrapunctual work. The product is a simultaneous display of cerebral mathematical precision and romantic warmth. There are few parallels to this in the repertoire. Moreover, it is filled with optimism, confidence and a spirit of defiance. It is tranquil, like Nerval’s lobster, and the perfect music by which to imagine that maritime creature on a promenade in the Palais-Royal. Unfortunately, no YouTube performance of this work has yet been posted, but if you can find it there is a wonderful recording by the Nash Ensemble.