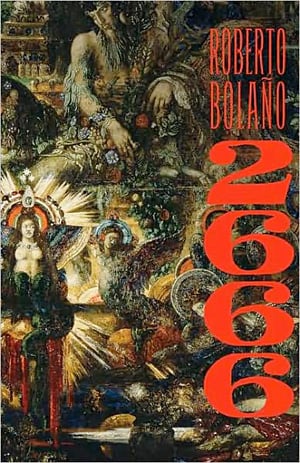

There are many ways of explaining the sudden, stratospheric popularity of Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño. At his essence he was a writer who was always thinking of new ways to use fiction, attempting to get things across to a reader who has seen it all. Bolaño himself was such a reader, and his books cunningly incorporate that awareness of fiction without turning the enterprise too terribly self-conscious (I would argue that The Savage Detectives courts, and sometimes is overcome by, a preening literary self-concsiousness that leaches life from the enterprise it’s trying so vigorously to stimulate, but that’s a 5,000 word conversation for another day). 2666, however (as in his perfect By Night in Chile), evades that tendency. Consider a paragraph from “The Part About the Critics,” from Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, in which two men discuss a difficult matter:

There are many ways of explaining the sudden, stratospheric popularity of Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño. At his essence he was a writer who was always thinking of new ways to use fiction, attempting to get things across to a reader who has seen it all. Bolaño himself was such a reader, and his books cunningly incorporate that awareness of fiction without turning the enterprise too terribly self-conscious (I would argue that The Savage Detectives courts, and sometimes is overcome by, a preening literary self-concsiousness that leaches life from the enterprise it’s trying so vigorously to stimulate, but that’s a 5,000 word conversation for another day). 2666, however (as in his perfect By Night in Chile), evades that tendency. Consider a paragraph from “The Part About the Critics,” from Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, in which two men discuss a difficult matter:

The first conversation began awkwardly, although Espinoza had been expecting Pelletier’s call, as if both men found it difficult to say what sooner or later they would have to say. The first twenty minutes were tragic in tone, with the word fate used ten times and the word friendship twenty-four times. Liz Norton’s name was spoken fifty times, nine of them in vain. The word Paris was said seven times, Madrid, eight. The word love was spoken twice, once by each man. The word horror was spoken six times and the word happiness once (by Espinoza). The word solution was said twelve times. The word solipsism seven times. The plural, nine times. The word structuralism once (Pelletier). The term American Literature three times. The words dinner or eating or breakfast or sandwich nineteen times. The words eyes or hands or hair fourteen times. Then the conversation proceeded more smoothy. Pelletier told Espinoza a joke in German and Espinoza laughed. In fact, they both laughed, wrapped up in the waves or whatever it was that linked their voices and ears across the dark fields and the wind and the snow of the Pyrenees and the rivers and the lonely roads and the separate and interminable suburbs surrounding Paris and Madrid.

The two men, Pelletier and Espinoza, close friends, both love Liz Norton. The conversation that we are overhearing is the one about the two men’s awareness of the other’s infatuation, as well as their awareness of the other’s carnal involvement with Norton. A difficult talk, and yet the nature of which one could imagine… having seen so-called ‘love triangles’ since the beginning of literary time. To thwart the reflex to cliché that such familiar territory courts, Bolaño has this ingenious notion of rendering the conversation statistically, keeping score with the two players. To those who have written me to say that can’t imagine why I dislike so violently the first sentence of A Canticle for Leibowitz, I offer these sentences as example of what I do like, very much. They leave something to the imagination, while, at the same time, present quite an imagination at work.