This is the story of the lake and the three big fish

that were in it, one of them intelligent,

another half-intelligent,

and the third, stupid.

Some fishermen came to the edge of the lake

with their nets. The three fish saw them.

The intelligent fish decided at once to leave,

to make the long, difficult trip to the ocean.

He thought,

“I won’t consult with these two on this.

They will only weaken my resolve, because they love

this place so. They call it home. Their ignorance

will keep them here.”

–Mawl?n? Jal?l-ad-D?n Muhammad R?m? (Rumi) (?????? ???? ????? ???? ????), Masnavi-ye Manavi (????? ?????), iv, 2203-86 (ca. 1265) (Coleman Barks transl.) from: The Essential Rumi

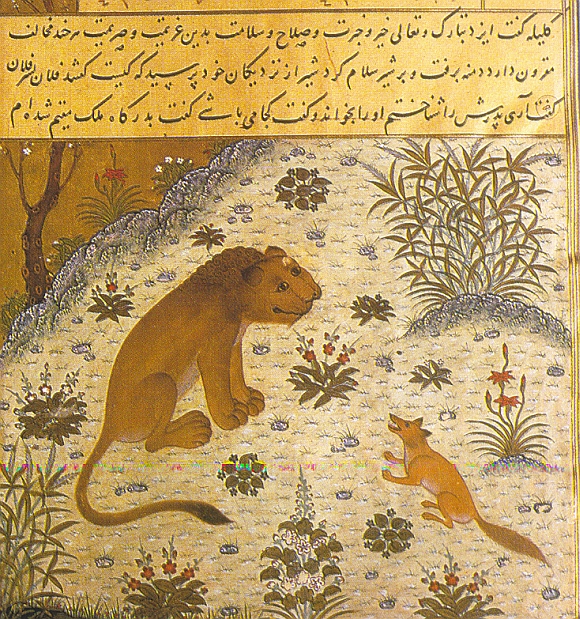

This is a story, as Rumi tells us in the prelude (in a passage that Coleman Barks decided not to include in his admirable translation), taken from the Sanskritic Five Principles or Panchatantra (??????????) from the third century BCE, a work which sets forth principles for the governance of a small state through a series of tales in which animals are introduced to present different aspects of the human nature. The book has been called a sort of Machiavelli of Indian antiquity by one of its scholars, since its purpose was apparently to teach young princelings in waiting the essential arts of statecraft. The Panchatantra was brought into Persia shortly before the age of Rumi, was translated and accommodated to Islamic ideas and values in some respects, and established itself as an instant classic. In his recounting, Rumi has adapted the fifteenth story from the first book of Kelileh va demneh, the name by which the book goes in Farsi, but he remains faithful to the essential political message of the original.

The major theme of this story is love of home, or patriotism, and its use and abuse by leaders. The story unfolds through the fate of three fish, one wise, one half-wise and the third a fool. (Barks uses the word “intelligent” instead of wise, which is arguable, but not perhaps the best translation.) Rumi does not challenge the notion that one should love his home, but he challenges us to ask, “Where is that actually?”

The foolish fish understands that the lake in which he was spawned and now lives is his home. He comes to the realization that this vision was false, but only too late, as he sits uncomfortably in a frying pan, about to be the meal of the men who have caught him. The foolish fish is bounded by the world of his immediate perceptions and needs. He lacks vision and foresight.

The half-wise fish is far more cunning in avoiding the traps and nets that the fishermen lay before him, so he escapes. But he is incapable of solving the riddle for himself. He needs a guide, which he recognizes is the wise fish. But the wise fish has set busily about saving himself and is gone. The half-wise fish is able enough, but he also is by his nature a follower who requires the guidance or intermediation of a greater one.

The wise fish recognizes that his true home is not the lake in which he has lived his life up to that point, but the boundless and infinite sea of which he has heard, but which he has never seen. The wise fish commits himself therefore to the quest for that true home, and he uses his skills and cunning to achieve that quest. He suffers and endures in the process, and achieves his goal.

Rumi warns us against those leaders who turn humans against humans with appeals to patriotism and love of home. Only a fool will allow this love, which is understandable and natural, to be transformed into hatred of others he does not know. In this way, he becomes the slave of the schemes and machinations of a nature which is clever but also base. Hence the first warning: Do not believe an absurdity, no matter who says it. These absurdities may and often do roll from the lips of persons set in authority above their fellow men. But those who preach hatred, distrust and hostility against other peoples do not merit our trust. They try to ensnare the feeble-minded with their bile. The foolish fish are their prey and they may capture some of the half-wise as well.

The fish, of course, represent human beings at different stages of awareness. (“The men of God are like fishes in the ocean,” Rumi writes elsewhere, “they pop up into view on the surface here and there and everywhere, as they please.”) But what, then is home? First, Rumi condemns as a fool the man who would define his home in terms of a political creation, be it city, state or empire. The true home is a boundless ocean, he writes. Man must think in terms of his species, linked across time and space. Equally he must cherish the planet on which he dwells and must avoid through love for any locality doing harm to the whole. But finally that “home” is something which the wiseman seeks, accepting suffering and loss as he does so. The way home, as Novalis would tell us, is an inward path.

To all my readers, a happy New Year filled with promise and hope, together with the resignation to bear the burdens that we must to achieve our goals, as each of us defines them. 2009 awaits us, offering new challenges, new obstacles and new prizes to be won. May each of you follow the way of that wise fish, avoid the traps that are placed in your way, detect the nets and swim around them, and ultimately make your way to that boundless ocean.