Quid est enim tempus? Quis hoc facile breuiterque explicauerit? Quis hoc ad uerbum de illo proferendum uel cogitatione comprehenderit? Quid autem familiarius et notius in loquendo commemoramus quam tempus? Et intellegimus utique cum id loquimur, intellegimus etiam cum alio loquente id audimus. Quid est ergo tempus? Si nemo ex me quærat, scio; si quærenti explicare uelim, nescio. Fidenter tamen dico scire me quod, si nihil præteriret, non esset præteritum tempus, et si nihil adueniret, non esset futurum tempus, et si nihil esset, non esset præsens tempus. Duo ergo illa tempora, præteritum et futurum, quomodo sunt, quando et præteritum iam non est et futurum nondum est? Præsens autem si semper esset præsens nec in præteritum transiret, non iam esset tempus, sed æternitas. Si ergo præsens, ut tempus sit, ideo fit, quia in præteritum transit, quomodo et hoc esse dicimus, cui causa, ut sit, illa est, quia non erit, ut scilicet non uere dicamus tempus esse, nisi quia tendit non esse?

For what is time? Who can easily and briefly explain it? Who even in thought can comprehend it, even to the pronouncing of a word concerning it? But what in speaking do we refer to more familiarly and knowingly than time? And certainly we understand when we speak of it; we understand also when we hear it spoken of by another. What, then, is time? If no one ask of me, I know; if I wish to explain to him who asks, I know not. Yet I say with confidence, that I know that if nothing passed away, there would not be past time; and if nothing were coming, there would not be future time; and if nothing were, there would not be present time. Those two times, therefore, past and future, how are they, when even the past now is not; and the future is not as yet? But should the present be always present, and should it not pass into time past, time truly it could not be, but eternity. If, then, time present — if it be time — only comes into existence because it passes into time past, how do we say that even this is, whose cause of being is that it shall not be — namely, so that we cannot truly say that time is, unless because it tends not to be?

—Augustine of Hippo, Confessiones lib xi, cap xiv, sec 17 (ca. 400 CE)

For the contemporary world, time seems a simple enough concept—it is measured and applied; our lives proceed according to schedules in which our needs and responsibilities and those of the communities in which we live are marked. Life quickly takes on a natural rhythm. But in the course of human history civilizations have risen and flourished with radically different ideas of time. Often they saw it as a sort of paradox, divided in three parts between past, present and future—but these ideas can be frustratingly difficult to conceptualize. For the early church fathers there was the further complication of understanding time in the sense in which it was used in scripture, as in the construction of the world, or the utterance of the word. These usages seem theologically impossible to reconcile with the every-day world’s understanding of time—they required the evolution of a concept of eternity distinct from time, the creation of a theological architecture of time that was apart from (but surrounded) the worldly one. Augustine is an important thinker for this purpose. He struggles with the idea of time, making many seemingly contradictory statements, but his objective is plain enough: to create a bridge between the philosophical (especially Aristotelian, from the fourth book of Physics) conceptualization of time and that implied by sacred texts. Aristotle presents us time as a sort of vanishing point, the fleeting instant of the present which is in some sense real whereas what is past and what lies in the future are illusory. But Augustine is concerned about the two lives of creatures with souls—the one of the temporal world (literally, the world of time), and the other of a spiritual world for which death marks a bridge.

But this is not to say that Augustine is rejecting Aristotle and his essentially scientific and inductive approach to time. He is relegating it to one sphere. Looking at cultures around the world, there can be little doubt that the attitude towards time has had great consequences for the evolution of arts and sciences. Those cultures which take the theologically oriented view of permanence and essential immutability inevitably tend to downplay the importance of the measurement of time. For the scientifically oriented, it was essential to escape the paradox of time through the development of a system of measurement that allowed a steady reckoning forwards and backwards and even of the present.

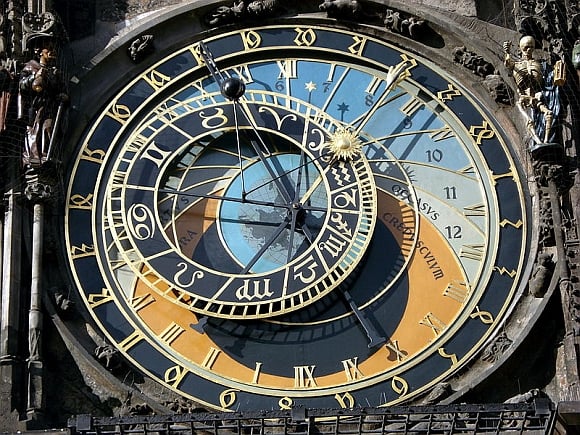

As the age of faith faded and the age of reason took hold in Europe, first in the Renaissance and then in the Enlightenment, it is no coincidence that this found expression in the development of mechanical approaches to the measurement of time: the clock. The utility of the clock was first seen in fixing the hours of prayer and religious services. But over time its essential role for science was discerned. Mastering the concept of time, and measuring time, was essential to an understanding of the heavens and to guiding the movement of vessels on the seas. Time might stand still for the theologian, but the universe was and is a place of perpetual motion.

But Augustine’s perspective continues to have a firm hold on the world of philosophy; it reminds us that we live not for the past or the future, but always for the present moment. It is only by our conduct in the present that we each can be measured.

Listen to John Dowland’s song Time Stands Still from the Third Booke of Songs or Ayres (1603) in a performance by Emma Kirkby on this Hyperion recording.