If the illustrated book for adults can, when the illustrations are undertaken by a hand less sophisticated than those of the author, produce an effect on the reader of distrust of the whole, the handmade book is one which aspires to, and regularly manages to, exalt the ideal of the book. Not that long ago, all books were handmade; now, most of the work is performed by armies of cleverly machined presses and binderies. Lost, in that consumptive progression, is not the beautiful book–for many special books made by machine do manage to be beautiful objects that function well. Lost is the ordinary book being routinely beautiful.

If the art of the handmade book is less available to the common reader, we must content ourselves with the uncommon pleasures it presents when we find them. Letterpress type is beautiful not merely because it is an expression of the earliest products of movable type, but because type that has been pressed into paper is often, to my eyes, more readable than text made up of ink applied to it or sprayed on it (much less the boondoggle of e-ink and its alleged readability). Several MFA programs across the country still teach the old art of movable type–and the making of paper, and the art of sewing books in signatures so that the pages of a beloved book don’t–as your favorite hardcovers of late do–fall out after two readings.

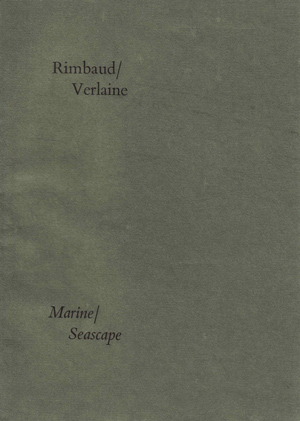

University of Iowa’s Center for the Book (UICB) has been minting, of late, graduate students who go on to to do beautiful work, as I recently learned. Talented book and print maker Lucy Brank produced, as her first handmade book as a student a small and lovely creature called Rimbaud/Verlaine, Marine/Seascape. Twelve pages long and printed, as Brank says in her colophon, “on a mysterious, unidentifiable Fabriano paper anonymously donated to UICB”, the book unites, for the first time, two poems of the same title by friends Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine.

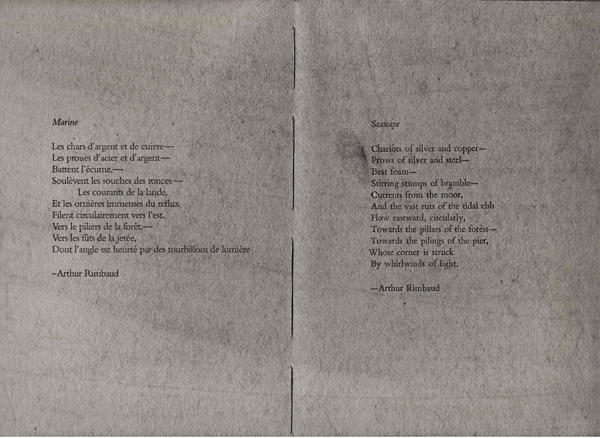

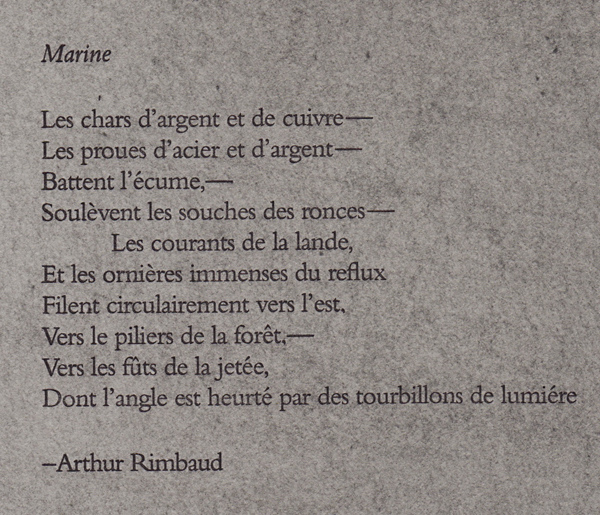

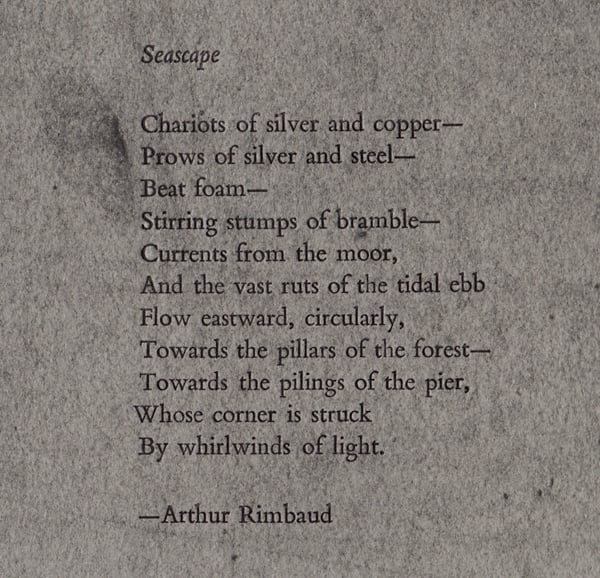

Brank begins studiously, with facing pages of French and English versions of each poet’s poem, using hand-set Bembo type.

As the translator of this version of “Marine,” Rimbaud’s little poem from his Illuminations, I find it an unusual pleasure to see the poem vividly set …

…and then reset so vividly as to make its translator not reproach its fidelity to the original (for once — translations are never fully satisfying to anyone, not least to their translators):

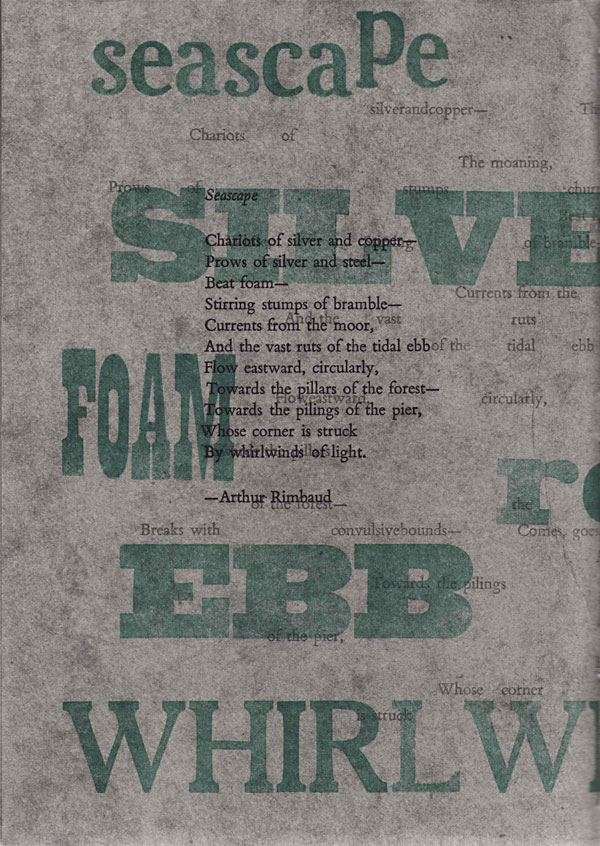

Fabulous fun though such crafty scruple is for the eye, Brank is up to more, in her Rimbaud/Verlaine, than rare clarity. She also has an artful ambition to make of two poems something more still, as one finds upon turning further:

Where we see the poem’s atoms begin to degrade, rising out of place and into space:

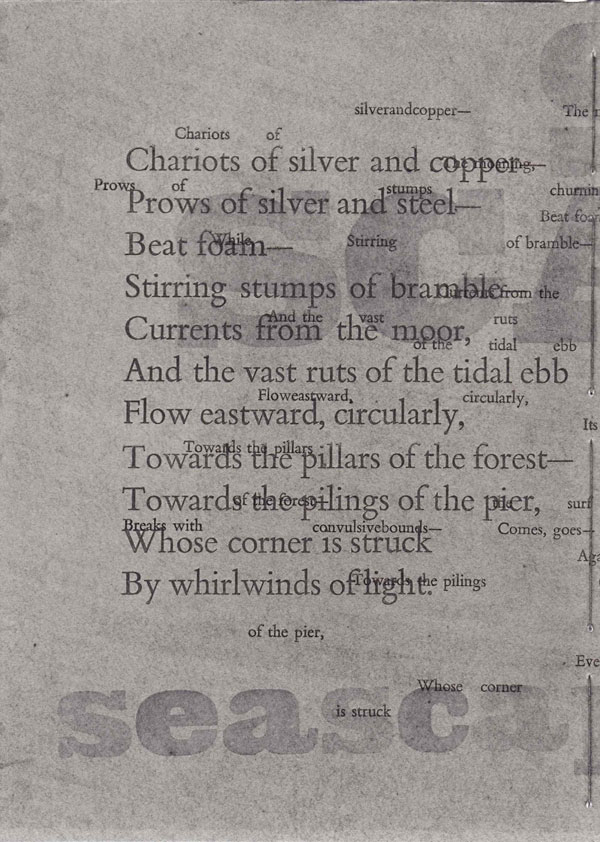

More fun still is the way Brank marries Verlaine and Rimbaud’s two poems on facing pages, producing a kind of typo-poetical cross-polination, a collision of not two but three artists’ visions. Faced with such beauty and rare industry, one can only look forward to more of Brank’s creations.