Readers familiar with Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature, Lectures on Russian Literature, and Lectures on Don Quixote, know that Nabokov had a very vivid way of reading the texts that he taught his students. A poor but passionate illustrator, Nabokov would sketch visual details from the various works he taught. Reproductions of his sketches appear in the published version of the lectures, and thus we see his drawing of Kafka’s Gregor Samsa in his metamorphosed state (whether “vermin” or “insect” or “cockroach” or Nabokov’s preferred “beetle” is another matter), a floor plan of the Samsa apartment, as well as the sort of skating costume that Kitty would have worn in Anna Karenina, or the sleeping car in which Anna rode from Moscow to St. Petersburg in same. The very useful and practical idea that one can get out of looking at Nabokov’s crude, charming illustrations of the text is that a work of literature is something to be looked at carefully, a thing one needs very much to learn, dedicatedly, how to see.

Readers familiar with Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature, Lectures on Russian Literature, and Lectures on Don Quixote, know that Nabokov had a very vivid way of reading the texts that he taught his students. A poor but passionate illustrator, Nabokov would sketch visual details from the various works he taught. Reproductions of his sketches appear in the published version of the lectures, and thus we see his drawing of Kafka’s Gregor Samsa in his metamorphosed state (whether “vermin” or “insect” or “cockroach” or Nabokov’s preferred “beetle” is another matter), a floor plan of the Samsa apartment, as well as the sort of skating costume that Kitty would have worn in Anna Karenina, or the sleeping car in which Anna rode from Moscow to St. Petersburg in same. The very useful and practical idea that one can get out of looking at Nabokov’s crude, charming illustrations of the text is that a work of literature is something to be looked at carefully, a thing one needs very much to learn, dedicatedly, how to see.

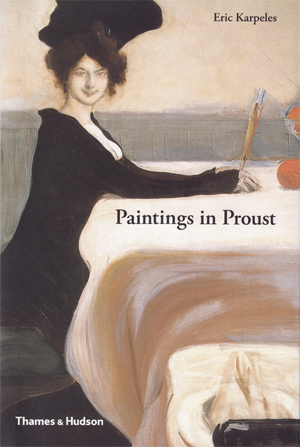

I suspect that Nabokov, first among many, would have found painter and writer Eric Karpeles‘s wonderful recent book Paintings in Proust: A Visual Companion to “In Search of Lost Time” something to be treasured. Karpeles takes as his very simple organizing principle the ambition to collect in one volume every painting Proust mentions in his large novel, a novel crammed with such references. “My book is a painting,” Proust wrote in a letter to Jean Cocteau, and Karpeles’s book is the first and only complete exhibition of those other painters upon whom Proust’s hungry eye came to feed.

A simple idea, but doubtless a cumbersome editorial task that Karpeles manages beautifully. He marches us through the novel’s seven parts and quotes the passages that mention each image or artist pairing them with the appropriate reproduction thereof (the text he uses is the Moncrieff/Kilmartin/Enright translation from Modern Library). Karpeles does a great service to readers in creating so practical and useful a book, one that enriches our appreciation and comprehension of the visual underpinnings of verbal art.

Paintings in Proust also happens to be one of the very prettiest examples of commercial publishing I’ve seen in a while. Produced (in China) with all the lavishness of a monograph, the book is sewn in signatures and printed on heavy glossy stock and lies open on a lap or a table. Fittingly, it will last forever.