Every day in America, on public radio stations across the land, a short program airs called “The Writer’s Almanac.” Hosted by the writer, musician and impresario Garrison Keillor, the show’s five minutes begin and end with a ceremonious progression of melancholic piano chords. Between these bookending strains, in his lulling baritone, Keillor catalogues the high-points of the date in literary history: which writer was born, what book appeared, who passed away. And then, before bidding us adieu (“Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.”), Keillor reads a poem. Though the authors he includes vary in age and gender, race and reputation, the poems themselves share a kind of soothing sameness–if not of subject or style or accomplishment then surely in the tone in which Keillor delivers them. Warm, winsome, tolerant, reassuring: whether the poem is one of longing or of losing, of joy or of grief, Keillor’s tone seems aimed at providing an almost analgesic relief to the listener — at proving that poetry is the balm that can heal any wound.

I find that tone a toxic thing, for it makes poetry into a kind of pillow, something puffed up and upon which one comes tiredly to rest. Whereas poetry at its best is a vigorous thing, an enlivening art, vibratingly alive, alive in its language and its music, a field of force and of forces. A poem in the collection Sunrise by American poet Frederick Seidel, suggests as much, concluding with the following lines, lines that give a potent sense of poetry’s better purpose:

At a very formal dinner party,

At which I met the woman I have loved the most

In my life, Belleville

Pulled out a sterling silver–plated revolver

And waved it around, pointing it at people, who smiled.

One didn’t know if the thing could be ?red.That is the poem.

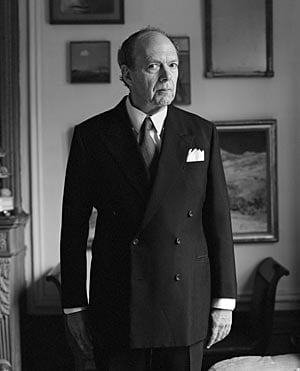

Frederick Seidel, for fifty years and across ten collections, has been writing our most serious, beautiful, and essential poems, poems that are shocking in their art and astonishing in their truth, and that remind us, in their forms, why poetry was once a vital part of cultural life (and not, as Keillor seems to have it, a respite from it). This week, Seidel’s collected Poems 1959-2009 appears, 500 pages of astonishments that renew the cultural definition of what a poem is: a thing that wakes us, shakes us, moves us, and pays equal attention to the details of living and the art of poetry.

The collection is already receiving intelligent attention. This magazine’s Christian Lorentzen has a fine essay in The National. Harper’s readers will also recall Benjamin Kunkel’s excellent essay on Seidel’s previous book,Ooga-Booga. As Kunkel wrote perceptively in these pages:

The suave tone setting up the shock, the excellent table manners combined with a savage display of appetite: this is what everyone notices in Seidel. Yet he wouldn’t be so special or powerful a poet of what’s cruel, corrupt, and horrifying had he not also lately shown himself to be a great poet of innocence. Critics have tended to miss or dismiss this in him, skipping ahead, as it were, to the good stuff. But for now let us go back to what, for Seidel, is clearly the beginning: the innocent oblivion that precedes everything. It seems that for him it is an important feature of a spoiled person, country, or planet (“Contorted and disfigured nature in the dying days of oil”) that at one time these things were nothing at all, and might just as easily have been almost anything else.

Poems 1959-2009 allows all of us to go back to Seidel’s beginnings, on his terms. This book of cunning art is itself a cunning thing: Seidel has organized his collected works backwards. Whereas one typically reads through a collected poems in the order that the collections first appeared, Seidel has ordered his from the most recent work to the most distant. Thus we begin by reading his new poems, those of the limited edition chapbook Evening Man, and march steadily backwards to Seidel’s first collection, Final Solutions. The effect of such inversion is an inversion of expectations: great poets’ early poems tend, when compared with those of the more mature writers they must become, to suffer by comparison. In Seidel’s case, what one notices as one reads towards his beginnings is how much of his present sensibility and capacity were already alive in his early work, and how dedicatedly he has tuned and challenged that sensibility as he has continued to surpass himself.

This Sunday, as your weekend read, I propose you spend a little time with Seidel. First, you can read many of Seidel’s poems online in the Google Preview of Poems 1959-2009, here. Begin, why don’t you, with “Boys”, a poem first published in Harper’s. And then, in the New York Times Magazine, you can read my profile of Seidel, wherein are included recordings of Seidel reading from his collected works (making it admittedly a weekend listen as much as a weekend read). Bon weekend.