Mitten im Schimmer der spiegelnden Wellen

Gleitet, wie Schwäne, der wankende Kahn:

Ach, auf der Freude sanftschimmernden Wellen

Gleitet die Seele dahin wie der Kahn;

Denn von dem Himmel herab auf die Wellen

Tanzet das Abendrot rund um den Kahn.

Über den Wipfeln des westlichen Haines

Winket uns freundlich der rötliche Schein;

Unter den Zweigen des östlichen Haines

Säuselt der Kalmus im rötlichen Schein;

Freude des Himmels und Ruhe des Haines

Atmet die Seel im errötenden Schein.

Ach, es entschwindet mit tauigem Flügel

Mir auf den wiegenden Wellen die Zeit;

Morgen entschwinde mit schimmerndem Flügel

Wieder wie gestern und heute die Zeit,

Bis ich auf höherem strahlendem Flügel

Selber entschwinde der wechselnden Zeit.

In the midst of the shimmer of the reflecting waves

Glides, swan-like, the rocking boat;

Oh on joy of these softly shimmering waves

Glides the soul along like the boat;

Then from Heavens down onto the waves

Dances the dusk all around the boat.

Over the treetops of the western grove

Waves happily toss in the reddish glow;

Under the branches of the eastern grove

The rushes murmur in the reddish gleam;

Joy of Heaven and the peace of the grove

Beathes the soul in the reddening glow.

Oh, time disappears on a dewy wing

for me, on the rocking waves;

Tomorrow, will disappear on shimmering wings

Time again as yesterday and today,

Until I, on a higher radiant wing,

Myself disappear taken by the passing time.

—Leopold Graf zu Stolberg, Lied Auf dem Wasser zu singen, für meine Agnes (1782) (S.H. transl.)

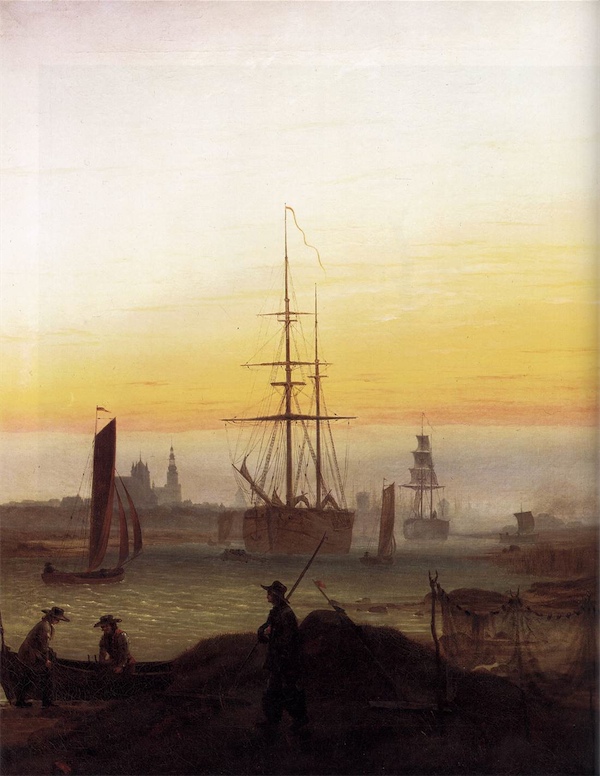

Count Stolberg was a Danish diplomat, poet and classicist, a significant star in the system that marked the transition from classicism to romanticism in late eighteenth century Middle Europe, and a man with one foot firmly planted in each camp. His poetry has been preserved largely because of Franz Schubert’s affection for it, and this Lied is surely one of Schubert’s most accomplished. He starts with a long sustained A flat minor, which warms up to an A flat major–it seems to be the movement between two different worlds, physically and emotionally. One is the red light of the day’s last glimmerings, and the other the dark afterworld that follows it. Schubert’s composition carefully marks the theme of the poem, the “shimmering” of the water, the “rocking” of the boat–note how skillfully Schubert does this, as he springs up an octave and then back down, mimicking the movement of the waves, with a quick punctuation suggesting the movement of a rudder, perhaps? But in doing this he is not just tracking the natural rhythm of the waves, but also the technique that Stolberg chose for the same purpose: note that his poem can be examined as a series of couplets, each with a line and a counter-line which contain language and images which are similar–but never quite the same. Specific words link the couplets, like a thread run through them. But the pairing technique is striking. Again, the movement of the waves, up and down. The poem suggests a state of approaching somnolence, perhaps of a dream. The world is seen in an eerily reddish light. It is a fading light. Darkness will soon close about and the image, wondrous, beautiful, soon will be lost to nightfall. The total effect of the song mirrors that of the poem. It is a curious series of juxtapositions and pairings–introspective and carefree, warmhearted and loving, straining to seize a moment of beauty and warmth, yet aware of the approach of darkness and death. Romanticist ideas have been suffused in a classical medium.

Listen to Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau sing Franz Schubert’s setting of this song, op. 72 (D. 774)(1823)