Yet Saadi loved the race of men,—

No churl, immured in cave or den;

In bower and hall

He wants them all,

Nor can dispense

With Persia for his audience;

They must give ear,

Grow red with joy and white with fear;

But he has no companion;

Come ten, or come a million,

Good Saadi dwells alone.

Be thou ware where Saadi dwells;

Wisdom of the gods is he,—

Entertain it reverently.

Gladly round that golden lamp

Sylvan deities encamp,

And simple maids and noble youth

Are welcome to the man of truth.

Most welcome they who need him most,

They feed the spring which they exhaust;

For greater need

Draws better deed:

But, critic, spare thy vanity,

Nor show thy pompous parts,

To vex with odious subtlety

The cheerer of men’s hearts.

…

Whispered the Muse in Saadi’s cot:

‘O gentle Saadi, listen not,

Tempted by thy praise of wit,

Or by thirst and appetite

For the talents not thine own,

To sons of contradiction.

Never, son of eastern morning,

Follow falsehood, follow scorning.

Denounce who will, who will deny,

And pile the hills to scale the sky;

Let theist, atheist, pantheist,

Define and wrangle how they list,

Fierce conserver, fierce destroyer,—

But thou, joy-giver and enjoyer,

Unknowing war, unknowing crime,

Gentle Saadi, mind thy rhyme;

Heed not what the brawlers say,

Heed thou only Saadi’s lay.

‘Let the great world bustle on

With war and trade, with camp and town;

A thousand men shall dig and eat;

At forge and furnace thousands sweat;

And thousands sail the purple sea,

And give or take the stroke of war,

Or crowd the market and bazaar;

Oft shall war end, and peace return,

And cities rise where cities burn,

Ere one man my hill shall climb,

Who can turn the golden rhyme.

Let them manage how they may,

Heed thou only Saadi’s lay.

Seek the living among the dead,—

Man in man is imprisonèd;

Barefooted Dervish is not poor,

If fate unlock his bosom’s door,

So that what his eye hath seen

His tongue can paint as bright, as keen;

And what his tender heart hath felt

With equal fire thy heart shalt melt.

For, whom the Muses smile upon,

And touch with soft persuasion,

His words like a storm-wind can bring

Terror and beauty on their wing;

In his every syllable

Lurketh Nature veritable;

And though he speak in midnight dark,—

In heaven no star, on earth no spark,—

Yet before the listener’s eye

Swims the world in ecstasy,

The forest waves, the morning breaks,

The pastures sleep, ripple the lakes,

Leaves twinkle, flowers like persons be,

And life pulsates in rock or tree.

Saadi, so far thy words shall reach:

Suns rise and set in Saadi’s speech!’

And thus to Saadi said the Muse:

‘Eat thou the bread which men refuse;

Flee from the goods which from thee flee;

Seek nothing,—Fortune seeketh thee.

Nor mount, nor dive; all good things keep

The midway of the eternal deep.

Wish not to fill the isles with eyes

To fetch thee birds of paradise:

On thine orchard’s edge belong

All the brags of plume and song;

Wise Ali’s sunbright sayings pass

For proverbs in the market-place:

Through mountains bored by regal art,

Toil whistles as he drives his cart.

Nor scour the seas, nor sift mankind,

A poet or a friend to find:

Behold, he watches at the door!

Behold his shadow on the floor!

Open innumerable doors

The heaven where unveiled Allah pours

The flood of truth, the flood of good,

The Seraph’s and the Cherub’s food.

Those doors are men: the Pariah hind

Admits thee to the perfect Mind.

Seek not beyond thy cottage wall

Redeemers that can yield thee all:

While thou sittest at thy door

On the desert’s yellow floor,

Listening to the gray-haired crones,

Foolish gossips, ancient drones,

Saadi, see! they rise in stature

To the height of mighty Nature,

And the secret stands revealed

Fraudulent Time in vain concealed,—

That blessed gods in servile masks

Plied for thee thy household tasks.’

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, excerpts from Saadi first published in The Dial, Oct., 1842 in: Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, vol. 9, pp. 136-41 (Riverside ed. 1911).

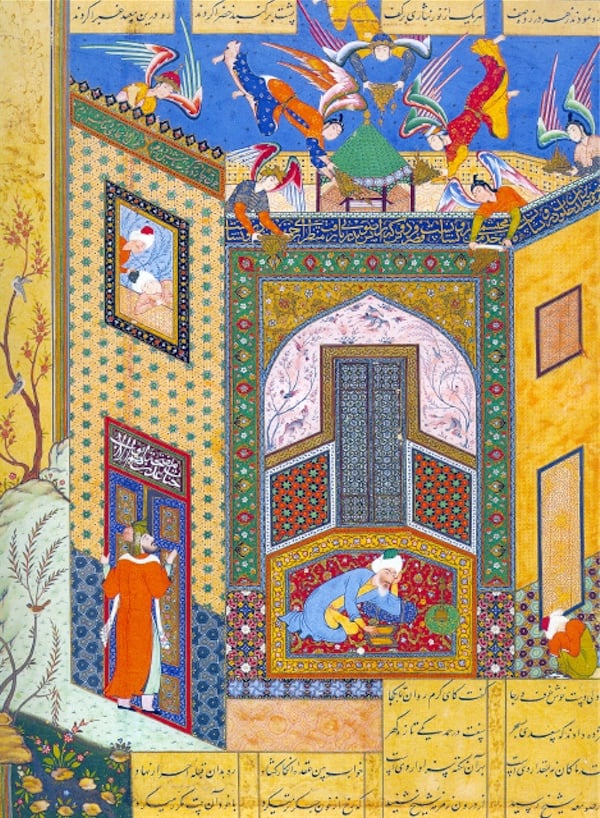

How distant and strange the developments appear today in Saadi’s country and with his people. How alien to Americans. But there was a time when America’s intelligentsia was enraptured by the ancient legacy of Persian letters, and found much guidance in it. Emerson’s poem Saadi bears witness to that era. It is a fascinating portrait of one of the great poets and thinkers of the Persian world who was being “discovered” in the early nineteenth century in Europe and America, but it may not really be so much about Saadi, the historical personage. It’s also one of Emerson’s most important poems. Emerson has selected Saadi as the embodiment of the ideal poetic spirit, the disposition that he strives to uphold. And remarkably, he sees nothing tragic in Saadi’s life and writings. Instead he sees a man with a Zen-like mastery of the world about him. He lives a contemplative life (“Unknowing war, unknowing crime”) yet is not altogether a hermit. To the contrary, he is a man who engages the world about him, offering teachings and lessons, building friendships, experiencing love (“Yet Saadi loved the race of men,—/ No churl, immured in cave or den.”) But he keeps the dark side of life perpetually at bay. (“For Saadi sat in the sun,/And thanks was his contrition.”) In this poem, more even than in his essays on Representative Men, Emerson’s objective is to “draw characters, not write lives.” So the historical Saadi is not necessarily his objective. And indeed, we have to ask ultimately: is Emerson looking back to the historical Saadi for his portrait, or is he not in fact holding a mirror before himself, painting the Emerson he wishes to be? In a journal entry of 1843, he seems to admit as much—was this poem really about Saadi, or was it about me, he asks.

But to be sure, Emerson is deeply engaged with Saadi and his writings. And what he sees in them looks an awful lot like New England transcendentalism. In the third book of Saadi’s Gulistan (or Rose Garden), Emerson reads the tale of the young laborer who prefers to eat the fruits of his own work and disdains the bread offered him by the gregarious Hatim Tai. For him, this is a parable of self-reliance. Similarly the repeated admonitions to his readers to be satisfied with what they have and not warped by desire for needful things. (In Gulistan we see this for instance in the passage in which a young man obsesses about his want of shoes, only to go to the mosque for prayer and meet there a man with no feet.) Likewise at the outset of the fifth book, we read the story of the young maid who is found beautiful by the sultan, but homely by all others. Each of these passages of Gulistan finds an echo in the poem Saadi.

In the closing months of the American Civil War, Emerson, who had been taken for much of the prior twenty years with the study of the Persian, and particularly Sufi poets, was asked to write an introduction for a new translation of the Gulistan. It was a time of trouble, bringing steady news of friends and loved-ones who had fallen in the war. But it was also a time of hope in the promise of the future. In his journal, as Emerson notes the commission, he writes: “Saadi is the poet of friendship, of love, of heroism, self-devotion, joy, bounty, serenity, and of the Divine Providence.” But as the short essay progresses, Emerson decides to stress the upbeat and affirming aspect of Saadi as a writer and thinker: “The word Saadi means fortunate. In him the trait is no result of levity, much less of convivial habit, but first of a happy nature, to which victory is habitual, easily shedding mishaps, with sensibility to pleasure, and with resources against pain. But it also results from the habitual perception of beneficent laws that control the world, he inspires in the reader a good hope.” Like Martin Luther King Jr., the philosopher-poet of Shiraz believes that the “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” May the arc be hastened in its course.