No man can have in his mind a conception of the future, for the future is not yet. But of our conceptions of the past, we make a future; or rather, call past, future relatively. Thus after a man hath been accustomed to see like antecedents followed by like consequents, whensoever he seeth the like come to pass to any thing he hath seen before, he looks there should follow it the same that followed then. As for example: because a man hath often seen offenses followed by punishment, when he seeth an offense in present, he thinketh a punishment to be consequent thereto. But consequent unto that which is present, men call future. And thus we make remembrance to be prevision, or conjecture of things to come, or expectation or presumption of the future.

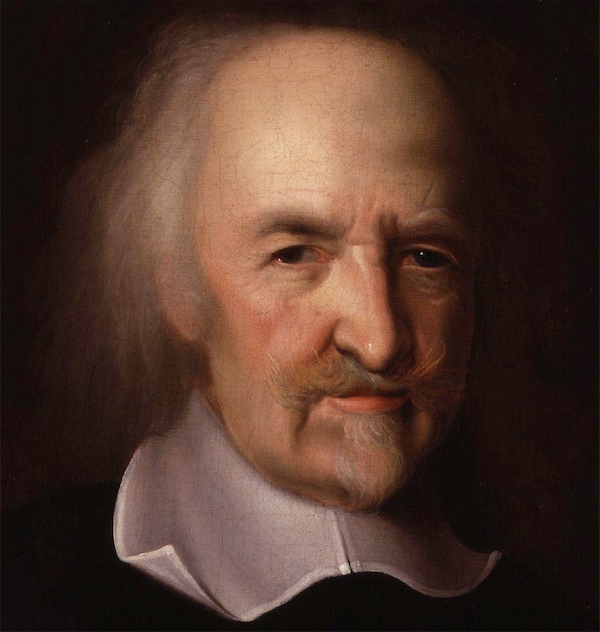

—Thomas Hobbes, The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic pt i, sec 7 (1650)

In seventeenth century England, that epoch that paved the way for the future that would be realized in America, there were two towering figures who advanced our understanding of the state and the proper relationship between subjects and sovereign. Indeed, subjects were on their way to being citizens, and the notion of a Divine Right monarchy was being shattered in favor of a government accountable to the people–but this movement had its counter-currents. One of these figures was Thomas Hobbes, a decided Royalist who viewed the emerging forces of revolution and reform with loathing even as he recognized their inevitability. The other was John Locke, the man who fills the gap between the world of the Puritan “saints” and the notions of tolerance and liberalism that began to take hold in the eighteenth century, reaching their logical fruition in the American Revolution. Hobbes, a committed advocate of the Royal Prerogative, stands at some distance from the forces that gave birth to America and was held in understandable suspicion by many of the Founding Fathers. But the last seven years have been a period of Hobbesian triumphalism in America. Dick Cheney’s political perspectives, we are told, were strongly shaped by his college encounter with Hobbes, his favorite political philosopher. The domestic policies of the Bush Administration–from the color-coded warning charts to endless reminders about 9/11–could be explained by reference to the works of Hobbes.

In a sense Cheney and Hobbes are a well matched pair. Hobbes is well known as a thinker of dark and troubling thoughts. His generally admiring contemporary biographer, John Aubrey, recounts how Hobbes amused himself while a student at Oxford by torturing birds. Hobbes sees the world as a setting for a “war of all against all” which renders the life of its human inhabitants “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Hobbes’s attitudes can perhaps best be understood against the backdrop of the English Civil War, in which he cast his lot with the losing Royalist party—a party which he then betrayed when the victory of the parliamentary forces was assured.

But Hobbes’s political analysis is subtle and perceptive; his method shows a scientific rigor. His conclusions rest on many observations that simply cannot be denied. He takes a very dim view of human nature and the natural tendency, particularly of politically active men, to seek steadily to expand their own power. Much as Hobbes disdained the Puritans, we can actually hear in his writings the echo of the Scots Calvinist Alexander Leighton—“we must understand with whom we live in this world, with men of strife, men of blood, having dragon’s hearts, serpent’s heads.” Of course, Hobbes and Leighton would have had diametrically opposed notions of who those “men of blood” were.

Hobbes appreciated the forces that brought down the monarchy and gave birth to the commonwealth, much as they brought discomfort and fear to his own life. He also recognized that the effort to frame the monarch’s power in terms of Divine Right had failed, and that the notion of social compact advanced by the Calvinists was ultimately more powerful. He sought to appropriate it and turn it to his own use to sustain the restored monarchy. Fear of chaos and violence, he reasons, leads men to cede power and authority to their ruler. That belongs to the Classic Comics version of Hobbes, of course. A key but less appreciated aspect of Hobbes theory is, however, what we might call the temporal element. Man is, he offers, an inherently conservative creature in that he seeks to preserve what he has and in so doing he is driven by his experience. In this sense, he suggests, man is a captive of his past—for out of his understanding of the past, he fashions for himself a future. Man is motivated by fear in this process. His fears are informed by historical experience. But the focus of his fears is the future: the prospect that horrible events of the past will recur. Hobbes’s prescription for would-be rulers is simple: to establish and sustain your mastery over men, understand how to manipulate the fears that drive them. Wield those fears to your own advantage.

For the past seven years, America has lived a Hobbesian moment. To be more precise, it has lived under political figures who sought to secure their hold on power through the use of a Hobbesian calculus. They believed that the traumatic experience of 9/11 could be used to gain ever more power and free themselves from the burdens of democratic accountability. This passage suggests how the process works: the experience of 9/11 coupled with fear of the prospect of its recurrence are manipulated to fashion a new future. This is what Hobbes means when he speaks of men fashioning a future from their perceptions of the past.

But is it really proper to say that Hobbes is focused on “fear” of the future? That’s certainly the Cheney take on Hobbes. But it might not be the best reading. What Hobbes has in mind may really be something a tad milder—not fear, but anxiety. Hobbes feels that concern about the future should drive man to be cautious, conservative and prudent—to avoid unnecessary risk-taking and to carefully calculate his interests and act to protect them. Anxiety should lead man to collective action and to minimize the recourse to state violence because of the very unpredictability of the consequences of war. He puts an emphasis on the controlled and directed force of reason. He does not mean the sort of fear that provokes panic and leads to unreasoned reflex. Hobbes does not contemplate fear that spurs rash decisions formed on the basis of preconceptions, ignoring evidence that disproved them. Can it be that America’s Hobbesian moment was based on a misreading of Hobbes? As I note in “Hobbes on the Euphrates,” the manner in which the would-be Hobbesians of the Bush era pursued the conquest and occupation of Iraq displayed an astonishing ignorance of the basic concepts of human interaction that Hobbes elucidates in the early chapters of the Leviathan. It’s clear that Thomas Hobbes was a far more insightful and thoughtful man than his self-styled disciples of the Bush era.

How did the philosopher of gloom dispel fear and avoid depression? Thomas Hobbes, it seems, was an intensely musical man. As Aubrey writes, he was “much addicted to music, and practised on the bass viol.” Hobbes launched his academic career as a mathematician and he took his practice on stringed instruments as an essentially mathematical exercise. It was one he pursued during his exile in Paris during the heyday of the great French violists. Listen to the Suite No. 1 in G Minor by Hobbes’s contemporary Matthew Locke in a performance by the Parley of Instruments. Locke was a leading viol player and performer of his day. Aubrey also notes that when depression struck, Hobbes had a routine he followed to deal with it. He would shut himself in at night and strike up songs to lift his spirits. He was particularly fond of the songs of Henry Lawes, a great though unfortunately now largely forgotten songwriter of the Commonwealth and Restoration. Listen to a performance of Lawes’s magnificent “Dialogue Upon a Kiss” taken from Ayres and Dialogues for One, Two and Three Voyces (1653), Hobbes’s favorite song book.