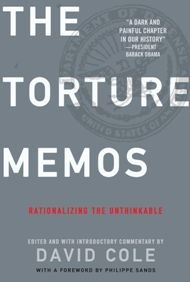

Six Questions for David Cole, Author of The Torture Memos: Rationalizing the Unthinkable

Georgetown law professor David Cole, a leading civil liberties advocate in relation to the “War on Terror,” has a new book out next week. The Torture Memos: Rationalizing the Unthinkable collects and reproduces in one volume the key Justice Department memoranda that authorized and insured the implementation of the Bush Administration’s torture program, together with critical commentary. I put six questions to Cole about his book and the newly emerging information about the role played by Justice Department lawyers from the CIA inspector general’s report.

1. Most of the discussion of the Justice Department Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) memos has thus far focused on their contents and legal reasoning, bypassing the role that the memos and their authors played in the overall process of introducing the Bush program. Do you agree, and if so, why does the instrumental role of the memos—as opposed to their content—really matter?

My view is that the OLC memos really are the “smoking gun” in the entire torture controversy. The chronology establishes that the OLC lawyers were central to the formation and establishment of the program, and that they may in fact have been so closely involved that it impaired their ability to offer an objective legal assessment. The full details will not be known until the Office of Professional Responsibility releases its report, and possibly not until there is a full-scale independent investigation, but the documents available now make clear that the OLC lawyers were intimately involved in every detail of this program from its very genesis.

What’s more, although much attention has been paid to the initial memo of August 1, 2002, because it was the first to be disclosed publicly, the subsequent memos, written in 2004 and 2005 but only recently released, are in some ways even more damning. They reveal that even as the law seemed to be getting more and more restrictive—with the precise purpose of making crystal clear that abusive tactics were not legal—the OLC lawyers continued to write secret memos interpreting those laws to permit precisely what they were designed to forbid. My book offers the chance to read the memos as a whole. When so considered, they reveal a concerted effort, first to contort the law to say “yes” where any fair reading of it would have said “no,” and then to cover the OLC’s tracks, in a sense, by ensuring that no subsequent memo would undermine or call into question the initial approval.

Thus, when the OLC publicly retracted the August 2002 memo and replaced it in 2004 with one that on the surface sounded more reasonable, the office went out of its way to ensure that the new memo would not preclude the CIA from any of the tactics it was employing, including waterboarding. And perhaps the most outrageous of all the memos is the one that has received the least attention—namely, a May 2005 memo, reproduced in the book, which opines that the full range of CIA tactics not only do not rise to the level of torture, but do not even constitute “cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment,” a much lower threshold.

All of this is especially disturbing, because the role of the OLC lawyer is to be the “constitutional conscience” of the executive branch. These lawyers are supposed to operate with a certain degree of independence and to provide candid and objective advice to the executive branch agencies. Their job is not simply to search for ways, no matter how strained, to say “yes,” but to be strong enough to say “no.” Under President Bush, on issues of torture, they never said “no.”

What should be done? Some, including former attorney general Michael Mukasey and former OLC head Jack Goldsmith, have argued that no further investigations, much less prosecutions, are needed. Mukasey insists that everyone acted in good faith, trying to draw difficult lines in trying times. Goldsmith maintains that we already know what happened, and that any further inquiry will render CIA agents too cautious and risk-adverse in fighting terrorism and other threats in the future. But the analysis above suggests that, while there were difficult judgments to be made, the desired result drove legal analysis rather than vice versa—and that is the very definition of bad faith. We certainly don’t know everything; Goldsmith’s role as head of OLC while the CIA’s tactics remain unauthorized is itself unclear, as are the roles of many who are likely to have been involved but did not sign any of the memos in question. And if an inquiry deters CIA agents from experimenting with brutality in the future, we should celebrate that, not bemoan it.

—From The Torture Memos: Rationalizing the Unthinkable

Reprinted by permission of the publisher, The New Press. Copyright (c) 2009 David Cole

2. On Monday, a new version of the CIA inspector general’s report on torture was released. What does this report tell you about the function played by the OLC memos?

The CIA IG report confirms what many have warned about—namely, that once you authorize the use of cruelty and physical abuse in interrogations, it is extremely difficult to halt the slippery slope toward even more brutal behavior. That is why the military has a long tradition of forbidding all physical coercion in interrogation (a tradition that Donald Rumsfeld broke from, also with the support of the OLC). This is an area where you need clear rules, and where, if you allow interrogators to treat their subjects as less than human, there may be no stopping them. Thus, the OLC memos do not authorize death threats, or threats to kill a suspect’s children, or physically throwing a suspect to the floor, but, according to the CIA inspector general’s report, all of those tactics were in fact employed.

The IG report also indicates that there was a lot of back and forth on the tactics employed. On one occasion, for example, Attorney General Ashcroft was briefed on the use of waterboarding—which in the case of Abu Zubaydah was employed 83 times. He is reported to have said that this was fully consistent with the principles in the OLC memos. Such oral representations may have in effect “expanded” the discretion that CIA interrogators thought they had. A full inquiry, then, needs to examine not only the memos—and they are bad enough, as I show in my book—but the entire course of oral and written communications that surrounded the program.

3. While releasing the CIA report, Holder decided to keep the wraps on the Department’s report on the torture memos, which was five years in the making and which has been sitting on his desk far longer. Why the extraordinary secrecy concerning the Office of Professional Responsibility report, and how do you expect it to complete our understanding of the torture memos?

It is a mystery to me why we have not yet seen the report of the Office of Professional Responsibility. But I think it could provide some key background information on the roles the lawyers played. It may suggest that they short-circuited certain review processes, to ensure a predetermined result. It may offer evidence to support what seems pretty clear from the face of the memos themselves: that the lawyers interpreted the law to conform to the CIA’s policies, rather than compelling the CIA to conform its conduct to the law. But at this point, we can only speculate.

4. Attorney General Holder has appointed John Durham, a career prosecutor, to review cases in which the CIA interrogation practices clearly exceeded what was authorized in the OLC memos and to decide whether a formal criminal investigation is warranted. Do you agree that a preliminary examination is appropriate? Are the limitations Holder imposed on this review reasonable?

There is no doubt in my mind that a preliminary investigation is warranted. But it should not stop at CIA interrogators. Holder and President Obama have both stated, point-blank, that waterboarding is torture. Except for Bush’s OLC lawyers, virtually every lawyer to consider the question has concluded similarly. The United States is under a legal obligation, imposed by the Convention Against Torture, to investigate and refer for prosecution any case in which a person within US jurisdiction is suspected of engaging in torture. We know that the OLC lawyers authorized waterboarding, and that Cabinet-level officials, including Vice President Dick Cheney, specifically approved of these tactics. We are therefore under a legal obligation to investigate them—and not merely the handful of interrogators who may have gone beyond waterboarding.

5. In his forward, Philippe Sands says the idea that lawyers involved in this process might be prosecuted once seemed “almost preposterous.” Now of course two investigating judges in Spain are looking at criminal charges against the Bush Administration lawyers who wrote the memos contained in your book. Yet, legal academics like Dean Chris Edley at Berkeley are closing ranks around John Yoo, arguing that however wrong, he did no more than give expression to unpopular views, and that he should therefore face neither criminal charges nor professional sanctions. Do you envision any form of accountability for the authors of the torture memos?

I hope that my book demonstrates that the lawyers are indeed culpable, by carefully analyzing the full range of arguments made while the CIA interrogation program was up and running. I believe that there must be some form of official accountability for these wrongs, and some official recognition that the illegality included the actions of the lawyers who wrote the memos and the Cabinet officials who authorized the tactics. Criminal prosecution, however, is just one form of accountability. There are other forms. They might include civil judgments against the perpetrators, the report of an independent commission, a censure or apology from Congress, bar disciplinary actions for lawyers, impeachment for Judge Bybee, or the dismissal of Professor John Yoo. I do not think we have enough facts yet to know what precise form of accountability is warranted for each individual. And therefore I think the best route for the moment would be an independent commission, armed with subpoena power, comprised of people who are trusted by all and above partisan politics, to conduct a full investigation. I am confident that if that happened, it would ultimately lead to some official recognition of the wrongs that were committed—and that is critical to ensuring that it not happen again.

6. What additional steps do you think the Obama Administration should take to redress the crimes committed through the introduction of the Bush Administration’s program of torture and official cruelty?

I applaud President Obama for closing the CIA black sites, terminating the “enhanced interrogation techniques,” releasing the OLC memos, and shifting responsibility for future interrogations from the CIA to the FBI. These are all important steps in restoring the rule of law, and their significance should not be minimized. However, the rule of law also demands accountability for legal wrongs, and in particular cannot abide an outcome that imposes accountability only on the politically insignificant, while leaving the politically powerful free and clear. I think at a minimum, then, the President should work with Congress to empanel and empower an independent blue-ribbon commission to investigate fully the CIA’s and the DOD’s use of brutal and physically coercive interrogation tactics, sparing no one from the inquiry. It will be time enough, once the facts are fully aired, to assess what the proper ultimate sanctions or judgments should be.