The decision to award President Barack Obama the Nobel Peace Prize produced a torrent of heckling from left and right. A consistent criticism is that Obama hasn’t yet acted as a statesman making peace, and some Republicans are harsher, saying the choice has “debased” the Nobel Prize or was a calculated slap in the face to the Republican Party and its leadership, particularly George W. Bush. But such criticism reflects a simple misunderstanding of the purposes of the prize.

It’s true that the award has on occasion gone to statesmen peacemakers, like the two former serving U.S. presidents who received it, Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. But if we survey the entire list, we find that the bulk of the recipients were not statesmen. More often than not, the recipient has been someone who helped shift the world dialogue in a specific direction, sometimes a person who rejected domestic chauvinism in favor of peace and suffered for it. Several of the recipients faced opprobrium in their home country for the award—that was the case for my client, the Russian physicist Andrei Sakharov, whose argument for peaceful coexistence and east-west convergence ran sharply contrary to the dogma of the Communist Party; and it was the case for Shirin Ebadi, the Iranian lawyer and human rights defender who received the prize in 2003. But the most striking single example may be a figure almost unknown in the English-speaking world who received the Nobel Prize for 1935, and who well demonstrates the considerations underlying the award.

Carl von Ossietzky was a high school dropout who developed a passion for great literature and philosophy and gradually became disaffected with the militaristic culture of his native Germany. After starting a career as a court clerk and pursuing literature as his passion at night, he gradually turned to journalism in the wild years of the Weimar Republic, eventually landing a post as the responsible editor of Die Weltbühne–the leading voice of opposition through the Weimar Republic’s slide into fascism. Von Ossietzky took it as a prime mission to expose German rearmament and militarization, which was being aggressively pursued under cloak of official secrecy even before the Nazis came to power in 1933. In March 1929, Die Weltbühne published a daring exposé about the rearmament of the Reichswehr, which was being pursued in secret and in violation of Germany’s treaty obligations. The government responded by prosecuting von Ossietzky for betrayal of state secrets, resulting in 1931 in his conviction and a sentence of 18 months.

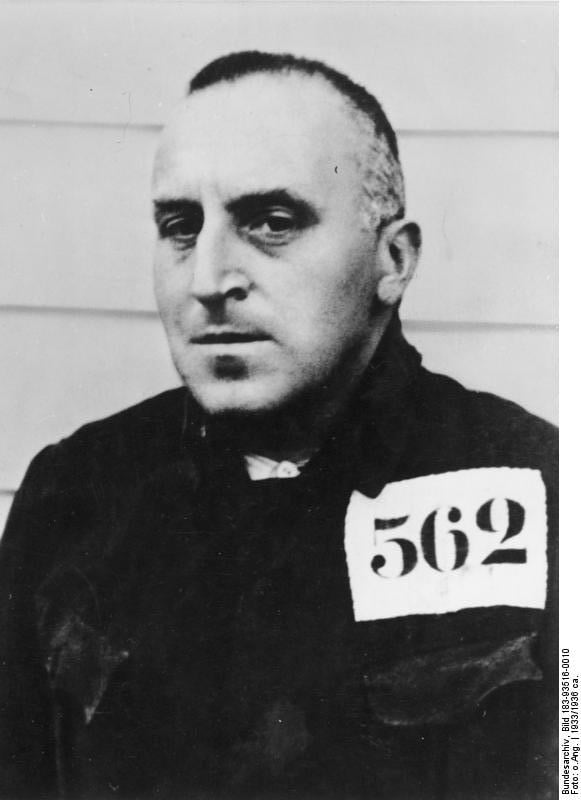

Whereas other dissidents responded to such acts of repression by seeking asylum in neighboring states like France, Sweden, and Czechoslovakia (and subsequently, in Britain and the United States), von Ossietzky insisted that the right thing to do was to go to prison as an act of protest. He served only part of his sentence and was released at the end of 1932 under an amnesty. However, within only weeks the Nazi Machtergreifung occurred, and von Ossietzsky was almost immediately arrested and interned again. The Nazis quickly began the construction of their network of concentration camps, and von Ossietzsky became one of their first internees. Subjected to a regime of hard labor and torture, he soon contracted tuberculosis, possibly as a result of medical experiments performed by Nazi doctors. In the fall of 1935, he was visited by a Swiss diplomat (Carl Jacob Burckhardt) who reported the encounter with a “trembling, deadly pale broken creature, who seemed to be without feeling, one eye swollen over, and his teeth bashed in.” He told the diplomat, “Thank you. Tell my friends that I have come to the end, soon it will be past and that is good… I only wanted peace.” Following public circulation of this report, the Nazis decided to release von Ossietzky to a state hospital under steady observation of the Gestapo on the eve of the 1936 Berlin Olympics. It was against this background that the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to him—largely the result of a campaign instigated and driven by a young German refugee in Norway named Willy Brandt.

German newspapers were forbidden to publish anything about the award except the tirades of the dictator, who called it an insult and proclaimed that no German would ever again receive this award. Placed under intense pressure by the Nazis to reject the award, von Ossietzky’s last act of defiance was to accept it. He died from the consequences of torture and tuberculosis in 1938.

What was the Nobel Committee recognizing by giving the award to Carl von Ossietzky, a man reviled by his fellow countrymen, accused and convicted of an act of treason? He sounded a clarion call about the rise of Nazism and the resurgence of German militarism, and he committed his life to their exposure. He tried to awaken the world to the threat they presented and nothing contributed more to the cause of world peace at this time than his wake-up call. In fact, at this time, leaders in Whitehall and in Washington saw Ossietzky and his associates as part of a hysterical fringe who were overstating the dangers of “Herr Hitler” and his movement. Seventy years later, however, the wisdom of the judgment of the Nobel Committee shines through.

How will the Obama award be judged in seventy years? Whenever the award goes to a political figure with a potentially long career ahead of him, the potential for embarrassment is enormous. So, the award to Obama is necessarily to some extent an expression of confidence in him as a politician. But this award clearly is focused on his ability to shift the course of international dialogue relating to peace. Many of Obama’s domestic critics are so absorbed with the debates over health care and other internal issues that they fail to understand the shift that Obama has already brought about on the international stage through a handful of steps. He extended a hand to the Islamic world in a striking speech delivered in Cairo. He revived flagging European confidence in the Atlantic Alliance (in which, by no coincidence, Norway has long been a stout-hearted member) by moving away from American unilateralism and back to a policy of closer coordination with traditional allies. He removed a key irritant from Russian relations with the west by pulling back a missile defense plan focusing on Poland and the Czech Republic and putting in its place one more genuinely attuned to the purposes that Bush articulated: defense against a missile threat from Iran. Finally, he has once again moved efforts to control the nuclear arsenal to the top of the agenda. These developments have been all but ignored in the United States, but they may ultimately prove of greater consequence than the inside-the-Beltway chatter that dominates our airwaves. In the contest between the Obama critics and the Norwegians on this point, I’ll put my money with the folks in Oslo.